This 100-Million-Year-Old Squid Relative Was Entrapped in Amber

The ancient ammonite was preserved alongside the remains of at least 40 other marine and terrestrial creatures

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/03/08/03082292-7e5c-4e6b-9a22-921cd5cb35d7/200432-1280x720.jpg)

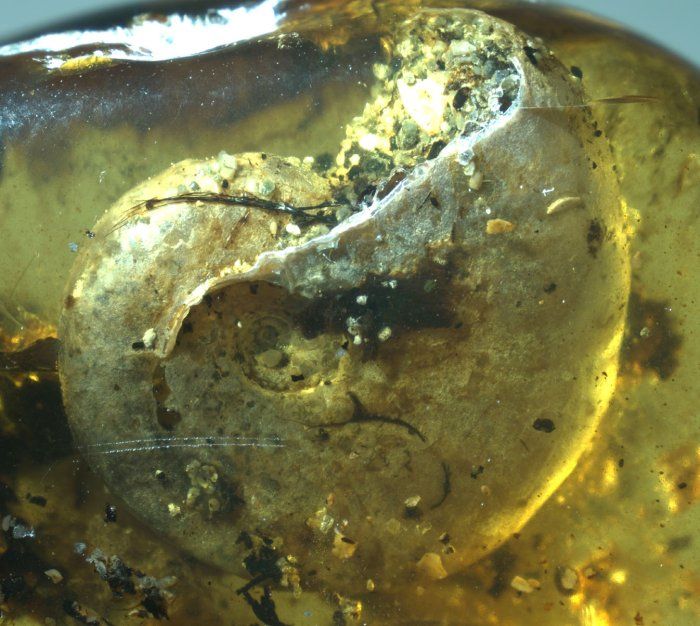

Around 100 million years ago, the remains of a misfit group of marine and land creatures were entrapped in viscous tree resin that eventually hardened into Burmese amber. Among others, the motley crew included four sea snails, four intertidal isopods, 22 mites, 12 insects, a millipede, and, most impressively, a juvenile ammonite, or extinct marine mollusk distantly related to modern squid and octopuses.

As Joshua Sokol reports for Science magazine, the three-centimeter chunk of fossilized tree resin—newly described in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences—holds the first known example of an amber-entombed ammonite. The critter is also one of the only marine organisms found in amber to date.

Given the fact that amber forms on land, it “commonly traps only some terrestrial insects, plants, or animals,” study co-author Bo Wang, a paleontologist at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology, tells National Geographic’s Michael Greshko. “It’s very rare to find ... sea animals in amber.”

The ammonite specimen is so singular, Greshko writes, that it as “eyebrow-raising as finding dinosaur remains on the bottom of an ancient seafloor.”

According to the Independent’s Phoebe Weston, all that remains of the mollusk is its shell, which is preserved alongside at least 40 other creatures, including spiders, millipedes, cockroaches, beetles, flies and wasps. Based on the lack of soft tissue present in the amber, scientists believe the organisms trapped within died long before encountering sticky tree resin in what is now northern Myanmar.

The study’s authors outline three main theories regarding the fossil’s formation. First, David Bressan explains for Forbes, the researchers posit that resin dripped down from a beachside tree, coating the remains of land and sea creatures previously stranded on the shore. Alternatively, it’s possible storm winds carried the ammonite shell and other animal remains into the forest. An unlikely but plausible final scenario involves tsunami-strength waves flooding a forest and depositing the ammonite into pools of resin.

As National Geographic’s Greshko writes, the amber sample came to scientists’ attention after Shanghai-based collector Fangyuan Xia purchased it for $750 from a dealer who had erroneously identified the ammonite as a land snail. According to Science’s Sokol, researchers used x-ray computerized tomography scans to take a closer look at the shell, which they confirmed as ammonite on the basis of its intricate internal chambers.

Ammonites, a group of shelled mollusks that ranged in size from a fraction of an inch to more than eight feet across, lived between 66 million and 400 million years ago, making them dinosaurs’ near-contemporaries. The juvenile ammonite in question belonged to the subgenus Puzosia, which emerged around 100 million years ago and died out around 93 million years ago.

The Puzosia ammonite now joins an impressive collection of animals forever frozen in amber’s honeyed hues. Previously, scientists have identified such scenes as a spider attacking a wasp, an ant beleaguered by a parasitic mite and a millipede seemingly suspended in mid-air. Much like the headline-making insect found entombed in opal earlier this year, the ammonite amber offers a visually appealing, contemplative glimpse into the distant past.

Jann Vendetti, a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County who was not involved in the new study, tells Greshko that the amber holds an “extraordinary assemblage, a true and beautiful snapshot of a beach in the Cretaceous [Period].”

David Dilcher, study co-author and a paleontologist at Indiana University Bloomington, echoes Vendetti’s emphasis on the specimen’s unexpected diversity, concluding, “The idea that there’s a whole community of organisms in association—that may prove more important in the long run.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)