Where Do Newly Hatched Baby Sea Turtles Go?

Special satellite tags that track baby sea turtles show that some ride the North Atlantic Gyre while others float in the Sargasso Sea

:focal(2273x1952:2274x1953)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/f1/9cf1bb41-f01e-45cc-b139-ef826ac4fdd0/satellite_tagged_neonate_loggerhead_released_in_gulf_stream_off_southeast_florida_coast_2009_jim_abernethy_nmfs_permit_1551.jpg)

The first few hours of a loggerhead sea turtle’s life are pretty exciting. After hatching in their beach nests, the baby turtles crawl clumsily into the Atlantic Ocean and swim out to sea.

But, what happens after these golf-ball-sized swimmers paddle off into the sunset? The time following their famous beach hatching ritual is a bit of a blur. Scientists call this period in a sea turtle's life the “lost years” because they don't have concrete evidence about what happens to them.

“We don’t know where the turtles go, how they get there, how they interact with their environment,” says Kate Mansfield, a marine biologist at the University of Central Florida. For loggerheads (Caretta caretta), the lost years phase lasts from 7 to 12 years. That's a huge chunk of life history about which sea turtle conservationists haven't a clue.

Mansfield’s team has found a way to fill in the blanks—by tagging and tracking baby turtles via satellite. According to their results, published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, baby sea turtles spend these adolescent years traversing long distances, floating in seaweed beds and hanging out at the ocean surface.

Studying sea turtles, let alone baby ones, on the open water is difficult and expensive, but that hasn’t stopped researchers from coming up with a few different hypotheses of how loggerhead turtles spend their time in the Atlantic. Because they would want to avoid predators like sharks and seabirds, babies likely stay away from the continental shelf, scientists figure. Scientists also think that floating communities in giant mats of seaweed of the genus Sargassum might be a good place for baby turtles. To conserve energy, neonatal sea turtles probably catch a ride on the Gulf Stream to drift with current of the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre. Like a giant lazy river, the gyre would supposedly transport them in a huge circle around the Atlantic. Baby turtles have been spotted amid seaweed beds and floating freely off the coast of North Atlantic islands as far away as the Azores, near Portugal.

But no one’s ever been able to physically track baby turtles to see whether or not these predictions hold any weight. To investigate, Kate Mansfield and her colleagues wanted to tag the creatures with some kind of instrument and then use satellites to track them where researchers can’t. However, tags typically used to monitor wildlife are too large for a baby turtle.

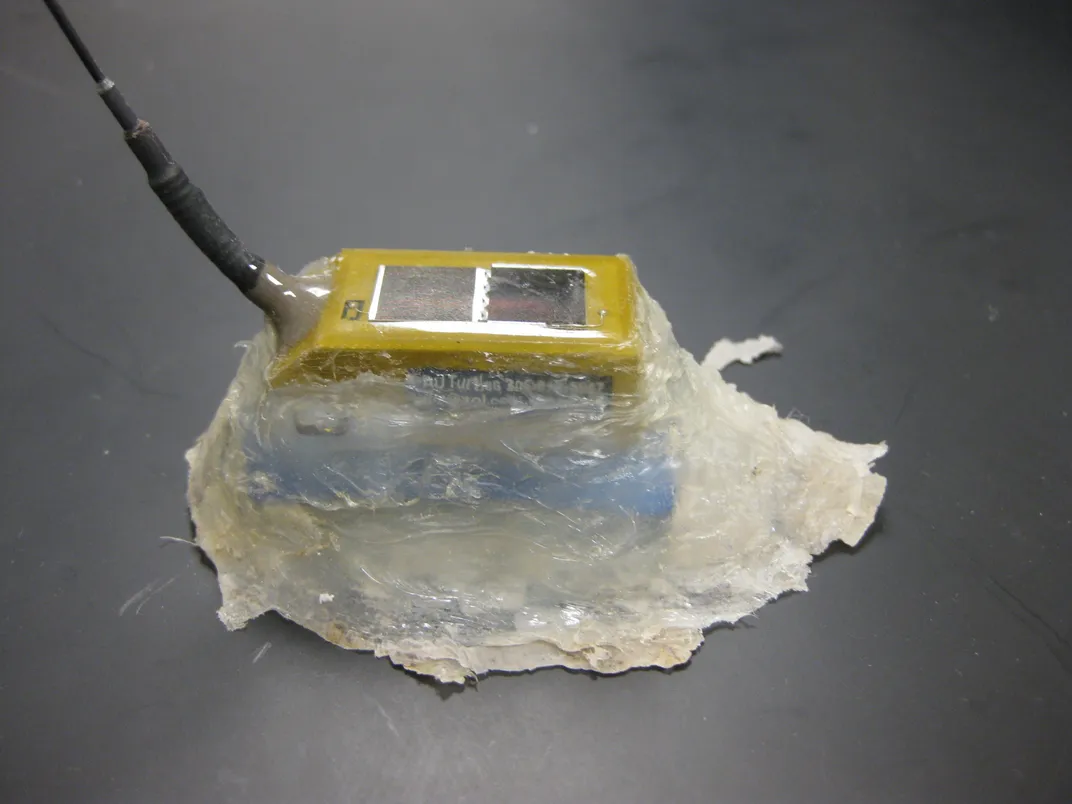

So Mansfield’s team developed a safe method of attaching solar-powered transmitter tags to the backs of baby loggerhead sea turtles. The tags are fairly small—imagine a couple cubes of “party cheese,” as Mansfield puts it. These cubes are then stuck to the back of a hatchling turtle using a mixture of silicone used to seal glass in aquariums and the same acrylic you might find in a nail salon. The small device is designed to allow room for growth as the turtle matures.

The team tagged 17 turtles, and released them into the Gulf Stream off of southeast Florida. As time passed, the tags transmitted location and temperature data to satellites circling the Earth. Mansfield received the data in an email from a satellite relay station.

Tags can only transmit data if exposed to air, so if a tag was charging and transmitting data, it had to be near the surface, soaking in the sunlight. Given this, researchers also used charge rate as a proxy for where the turtles were in the water column. In this way, the turtles were tracked for 27 to 220 days, depending on the turtle.

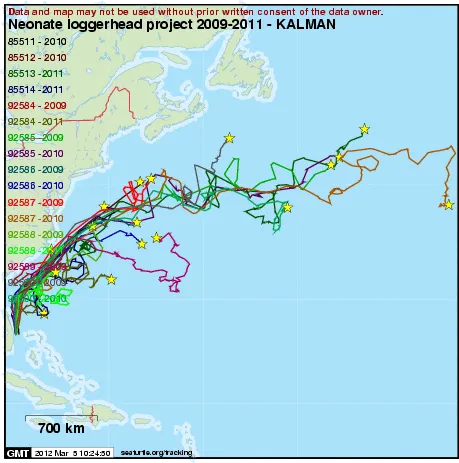

“We were surprised by how quickly the turtles traveled and how far they traveled,” says Mansfield. For example, one turtle took only 11 days to make it from West Palm Beach, Florida, to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina—a roughly 700-mile trip when you factor in the turtle's floating route, Mansfield estimates.

On the whole, the data back up the longstanding hypotheses with solid tracking data instead of anecdotal sightings of turtles from passing ships or in coastal regions. Most turtles steered clear of the continental shelf, but there was a lot of variation in their routes: a number of turtles left the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre and entered the Sargasso Sea, a calm region in the middle of the circulating gyre where floating Sargassum collects.

Previous lab studies have suggested that the turtles seek to stay within the currents of the gyre, but it makes sense that some turtles might leave the current and take advantage of foraging opportunities afforded by the wealth of seaweed beds in the Sargasso Sea. The satellite data also points to hatchling turtles spending a lot of time at the ocean surface, so Mansfield and her team began to wonder if there was some kind of thermal advantage for baby turtles to either stay near the surface or hang out in a big bed of seaweed. Turtles are cold blooded, and temperature in the ocean water column can vary a lot. If things get too chilly, a turtle's metabolism can slow down. Could seaweed act as a kind of insulator?

In the lab, the team measured the solar reflectivity of Sargassum and a turtle shell using a spectroradiometer, and found that they both reflected about 10% of the light energy that hit their surfaces—meaning both turtle shells and seaweed can help to keep the creatures warm in the open ocean. So in addition to being a great place to forage for food, Sargassum beds come with a thermal benefit, Mansfield explains. Because the seaweed absorbs a lot of heat from sunlight, water just below the surface of the seaweed tends to be warmer than surrounding water.

And if turtles can manage to stay warm, "their metabolism kicks in and they start feeding more, and they may grow faster,” explains Mansfield. “So, temperature can also help turtles grow and survive.” That’s at least one reason the surface and seaweed are a baby turtle’s two favorite hang-outs.

However, this thermal niche may be fragile. “With changes in the global climate, the thermal landscape the turtles encounter will likely shift and change. There may be changes in ocean circulation patterns, too,” says Mansfield.

It's hard to predict exactly how sea turtle communities may be affected. But now, thanks to satellite tracking's new ability to monitor the early lives of turtles, science may soon be able to better inform conservation strategies.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)