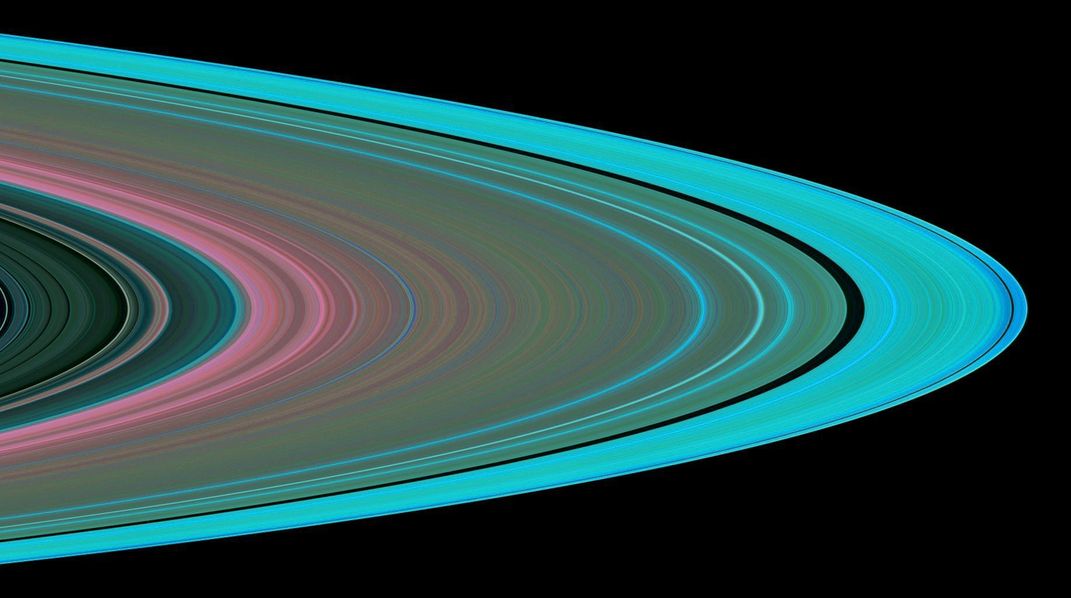

How and When Did Saturn Get Those Magnificent Rings?

The planet’s rings are coy when it comes to revealing their age, but astronomers are getting closer

:focal(655x218:656x219)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/69/c469f647-2d3a-4c0c-81fe-52fe355abee9/54_18_pia18357_full.jpg)

Cassini, the little spacecraft that could, is going out in a blaze. For the next four months, the most sophisticated probe ever made will dance precariously between the Saturn and her icy rings, capturing spectacular images of this never-explored region. In this grand finale to its 20-year journey, Cassini will draw new attention to the origins of what are already the most glamorous—and mystifying—set of rings in the solar system.

For astronomers, the most enduring mystery about these rings is their age. Although long considered ancient, in recent years their decrepitude has come under debate, with evidence suggesting a more youthful formation. Now new research supports the idea that Saturn’s rings are billions—rather than millions—of years old.

At some point in Saturn’s history, a disk of dust and gas around the moon coalesced into the incredible rings we see today. Some of the moons that dart in and out of those rings may have formed from the same material, meaning that dating those moons could help us zero in on the age of Saturn’s rings. But according to the new research, three of those inner moons are older than scientists had had hypothesized—hinting at an ancient origin for the rings as well.

“It is a very cool puzzle, because everything is linked,” said Edgard Rivera-Valentin, at Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Rather than tackle the ages of all of the moons and rings, Rivera-Valentin is slowly working his way through the challenge, step-by-step. “I’m trying to cut out one piece” of the puzzle, he says.

In 2016, Rivera-Valentin started using new computer models to examine the collisional history of the Saturn’s moons Iapetus and Rhea, and found that they had formed early on in the 4.6-billion-year life of the solar system. His findings, which he presented at the Lunar and Planetary Sciences conference in Texas in March, support the idea that Saturn’s rings are older than we thought.

In addition to being intriguing in their own right, Saturn's rings and moons may offer hints for those hunting ringed planets outside our own solar system. So far, only one ringed exoplanet has been identified—which seems strange, given that all four gas giants in our own system boast rings. If Saturn’s moons and rings are young, that could provide an explanation.

“If Saturn’s rings are young, then a (hypothetical) observer looking at our solar system would not have seen them if looking, say, one billion years ago,” said Francis Nimmo, a planetary scientist who studies the origins of icy worlds at the University of California at Santa Cruz.

Perhaps other worlds also have short-lived rings, whose brief appearances in the long lens of spacetime make them difficult to spot from Earth. In that case, just as someone beyond the solar system would have a limited opportunity to spy rings around Saturn, human observers would be similarly limited in their ability to spot ringed exoworlds.

Long-lived moons and rings, on the other hand, could mean that such worlds are common and could be hiding in plain sight—either lost in decades of data, or stymied by technological limitations.

Ancient scars

When it comes to calculating the ages of other worlds, scientists rely heavily on craters. By linking impact scars to periods of heavy bombardment in the solar system, they can roughly estimate how old the surface is, which provides an upper limit on the world itself. Previous research has suggested that Saturn’s rings and moons are just 100 million years old, making them relatively young in the life of the solar system.

The problem is, how the solar system behaved in the past is a subject of ongoing debate. In 2005, a new theory emerged that had Uranus and Neptune dancing with one another, slinging icy debris inward towards the rest of the planets. But according to Rivera-Valentin’s research, this rain of material (known as the Late Heavy Bombardment) would have totally destroyed Saturn’s youngest moon, Mimas.

Rivera-Valentin decided to work the problem from the other end. In the past, he’d worked with a student to calculate how much debris slammed into Iapetus, which he says should be the oldest moon under any model. By using a similar technique to figure out how much material scarred another moon, Rhea, he found that the satellite was bombarded far less than Iapetus.

That could be because the amount of material hitting the moon was smaller than previously calculated. Or, it could be because Rhea formed much later than Iapetus, perhaps soon after the Late Heavy Bombardment that took place 3.9 billion years ago. But based on crater counts, Rhea’s scars mean it can’t be quite as young as some models predicted.

“So the model that said they could have formed 100 million years ago, I can at least say no, that’s probably not the case,” Rivera-Valentin said. However, models suggesting Rhea formed around the time of the Late Heavy Bombardment all work with the moon’s cratering history. By striking down one of the supports for younger rings, Rivera-Valentin’s research has helped build the case that Saturn’s satellites have a far older origin.

Turning back the clock

Since the cratering history method is so dependent on our understanding of how the solar system evolved, Nimmo decided to take a different tactic to pursue the ages of the moon. His studies revealed that the moon must be at least a few hundred million years old, ruling out the models that set it at only 100 million years.

“You can sort of wind the clock back and see where they were at earlier times,” Nimmo said. Previous research on the subject put Mimas right next to Saturn only half a billion years ago, suggesting that it could have been young. However, that research assumed that the moons behaved the same way in the past that they do today.

Nimmo, on the other hand, explored how they could have interacted differently when they were younger. “Even though the satellites are moving out quite fast right now, they weren’t moving out as fast earlier on, and so the satellites can easily be 4 billion years old,” he said.

Nimmo unwound the dynamics of two of the more than 60 moons to find more evidence of their ancient formation. Unlike previous model that rewound the moons based on their orbits today, he accounted for how Saturn would have influenced the moons. Saturn tugs at the moons as they orbit, and the moons tug at one another. These constant pulls heat their centers, and the heat then moves toward the surface.

“It takes time for that temperature to propagate outwards, because heat only gets conducted at a certain rate, so this is a time scale that we can use,” he said.

On Dione, flowing ice has filled some of the impact basins. If the collision itself had melted the ice, the craters would have relaxed into the surface, Nimmo said. Instead, the heat must come from the neighborly tugging. He used the melting as a thermometer to determine that the moon is a minimum of a few hundred million years old, though it could easily have been around for 4.5 billion years. That rules out models that date the moon at only 100 million years.

In future studies, Nimmo hopes to examine other moon like Tethys, whose rapid motion should help narrow down the time around its birth. And although his research, which builds upon previous work done by Jim Fuller at the California Institute of Technology, provides some constraints on the birth of the satellites, the age gap remains large. “It’s not going to solve everything,” he said.

Ringed exoplanets

So far, the only known ringed exoplanet is J1407b, a young world that sports monster rings 200 times larger than Saturn’s and could resemble the gas giants of the early solar system.

“The idea is that Saturn’s rings were once that big,” said Matt Kenworthy of Leiden Observatory, who led the team that identified the monster rings in 2015. Over time, the gas and dust may have formed moons, fallen on the surface, or been blown away by the solar wind. Understanding if the moons, and potentially the rings, are ancient can help reveal if Saturn carries the remnants of these primordial rings.

If Saturn’s rings are old, that should mean they exist around other exoplanets. So why has only one world been identified so far? According to Kenworthy, that’s due in part to time. Spotting a gas giant far enough from its sun to hold onto icy rings requires about 10 years worth of data, information that has only recently been compiled.

“We’ve probably stumbled on one of many which are already sitting in the data, and it’s just a matter of digging through old data,” Kenworthy said.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/NTR_headshot.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/NTR_headshot.jpg)