When the Arctic Gets Warmer, It Also Affects a Tropical Ecosystem Thousands of Miles Away

As spring arrives earlier in far northern Russia, red knots get smaller—and have trouble in their African winter homes

Nowhere in the world is warming as fast as the Arctic. Temperatures there are rising twice as quickly as the rest of the globe. Permafrost and sea ice are melting, and springs are arriving earlier.

Animals have begun to change in response to these new conditions. And some of them, researchers have found, have shrunk in size. Some scientists thought this might be an adaptation to a warmer world; smaller bodies have a higher ratio of surface area to volume and should be able to dissipate heat better. But now a new study published in Science has found that for red knot birds, that’s not the case. Getting smaller is harmful to the birds’ chance of survival, and this may even be affecting an important ecosystem half a world away.

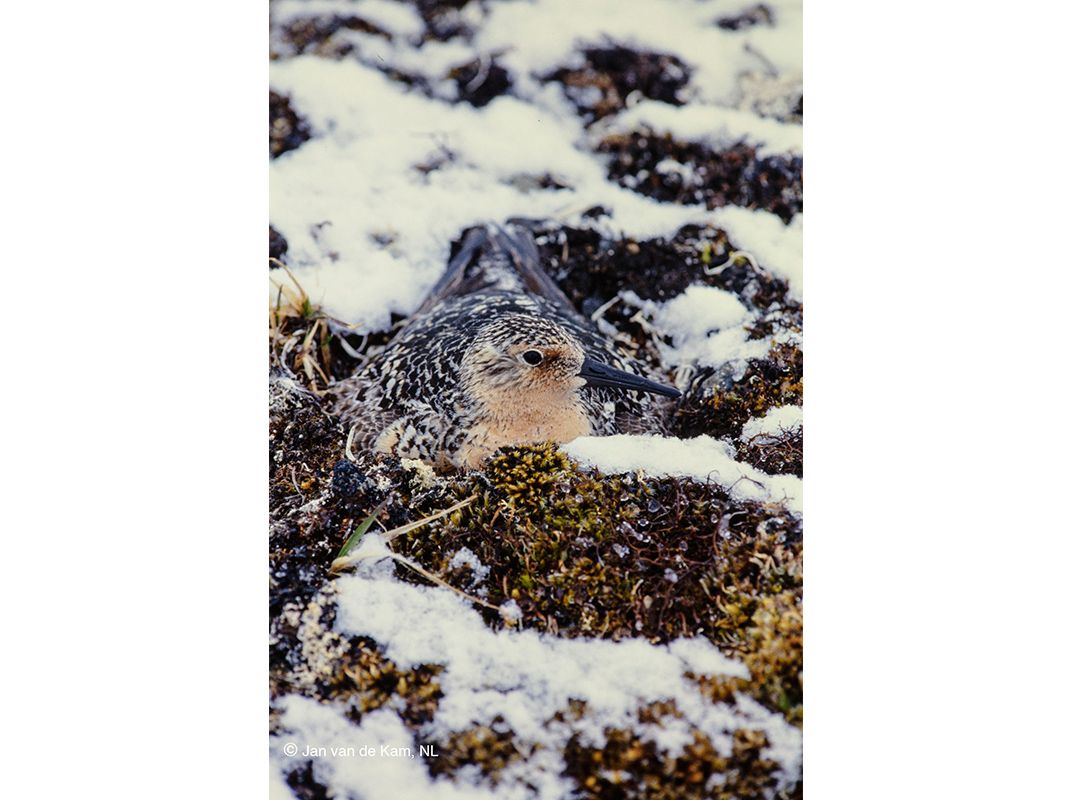

Red knots of the subspecies Calidris canutus canutus summer and breed in far northern Russia on the Taimyr Peninsula and winter along the coast of Western Africa. They make the journey between their two homes in two 2,500-mile-long flights, each lasting several days, with a stop in the Netherlands in between.

Ecologist Jan van Gils of the NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research and Utrecht University and his colleagues have been studying these birds for 33 years. “It’s a relatively easy species to study,” he says, in part because the birds can be easily raised in captivity. “They can become really tame and start eating out of your hand.”

Over the course of their research, van Gils and his team have found that on the peninsula where the red knots summer, snowmelt has been occurring earlier and earlier. Some years it arrived on time, some years really early, and others a little late. But on average, snowmelt, and spring, there has been advancing by half a day per year.

These earlier snowmelts are affecting the red knots. Over three decades, the researchers caught and measured nearly 2,000 birds as they flew through Poland on their way south. In years when the snowmelt had arrived particularly early, the birds tended to be smaller and have shorter bills.

“We think what is happening is a trophic mismatch,” van Gils says. The birds leave the tropics and fly north toward Russia with no clue as to what the weather is like there. The birds are supposed to arrive so they can lay their eggs and time the hatching of their chicks with when there will be a wealth of arthropod insects to feed their young.

But even though the red knots are showing up a little earlier every year, they are advancing their arrival date by only about a quarter of a day per year—not enough to keep up with the snowmelt. And in years when the snowmelt arrives early, the arthropods peak before the birds need them, chicks miss out on eating well and they grow up to be smaller and have shorter bills.

Being smaller and having a shorter bill isn’t a problem in Russia—but it is in Mauritania. There, adult birds feed on thin-shelled bivalves, Loripes lucinalis, swallowing them whole and then crushing them in their gizzards. “But that favorite prey is also a complicated prey,” van Gils says. The bivalves are buried deep, and they are also slightly toxic and cause diarrhea in the birds. “We think that as a juvenile they have to learn physiologically…how to treat this prey,” he says. But that learning is worth it because the other option—a diet of rare Dosinia isocardia bivalves and seagrass rhizomes—which only the youngest birds rely on, isn’t as abundant or nutritious.

Van Gils and his colleagues found that, in their first year, shorter-billed red knots don’t survive as well in the tropics, probably because they can’t access the L. lucinalis bivalves and make the dietary switch. “There will be a few short-billed birds that made it,” van Gils says, “but the majority of birds that survive [are] the long-billed birds.” And in years following those early snowmelts, fewer juveniles survived their winter in Africa, the team found.

Smaller or fewer red knots could affect their winter habitat in a couple of ways, van Gils speculates. Red knots in Mauritania live among seagrasses, which form the base of a key shore ecosystem that provides food and shelter for a diverse range of organisms. Disrupting or changing what the red knots eat, or having fewer of the birds around, could negatively affect the seagrasses. “It’s really different, a poorer system without seagrass,” he says.

“These results show that global warming affects life in unanticipated ways,” Martin Wikelski of the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology and Grigori Tertitski of the Russian Academy of Sciences write in an accompanying commentary.

It’s difficult to say exactly what is happening to the shorter-billed birds the disappeared, Wikelski and Tertitski note. The study by van Gils and his colleagues assumes, as most bird studies do, that red knots that don’t show up where expected have died. And it’s possible that some of those missing birds have instead forged new paths and established new populations. “Only by tracking the development and morphology of individual birds throughout their life can researchers fully understand the population consequences of environmental change,” they write. And this is something that, while difficult and time consuming, researchers are starting to do.

But van Gils notes that he and his colleagues have seen a similar “maladaptation” to climate change in another Arctic bird, the bar-tailed godwit. “We also see that this species is getting smaller [and a] shorter bill,” he says. With two species undergoing similar changes, he posits, this may be “a really general phenomenon that happens in a lot of high Arctic breeders.”

It can be tempting to think that seeing animals or plants change in response to warming temperatures is an example of organisms adapting to a new normal and that these species will do just fine in response to climate change, but that is a “dangerous hypothesis,” van Gils says. “We see that getting smaller is actually a warning signal.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)