The Unsettling Beauty of Lethal Pathogens

British artist Luke Jerram’s handblown glass sculptures show the visual complexity and delicacy of E. coli, swine flu, malaria and other killing agents

![]()

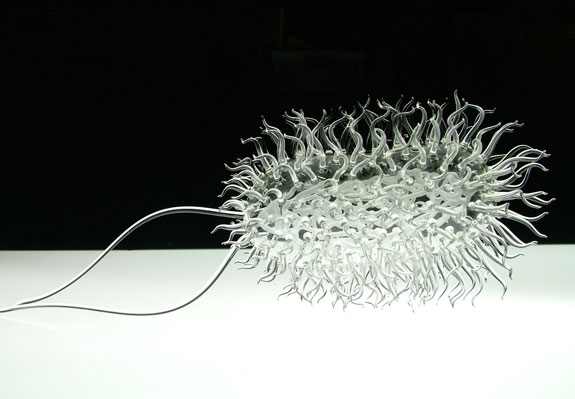

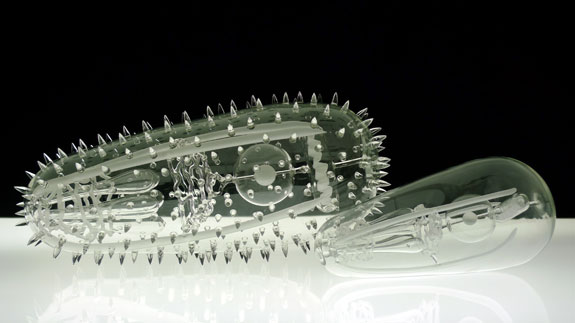

Few non-scientists would be able to distinguish the E. coli virus bacteria from the HIV virus under a microscope. Artist Luke Jerram, however, can describe in intricate detail the shapes of a slew of deadly viruses pathogens. He is intrigued by them, as a subject matter, because of their inherent irony. That is, something as virulent as SARS can actually, in its physical form, be quite delicate.

Clearly adept at scientific work—as an undergraduate, the Brit was offered a spot on a university engineering program—Jerram chose to pursue art instead. “Scientists and artists start by asking similar questions about the natural world,” he told SEED magazine in a 2009 interview. “They just end up with completely different answers.”

To create a body of work he calls “Glass Microbiology,” Jerram has enlisted the help of virologist Andrew Davidson from the University of Bristol and the expertise of professional glassblowers Kim George, Brian George and Norman Veitch. Together, the cross-disciplinary team brings hazardous pathogens, such as the H1N1 virus or HIV, to light in translucent glass forms.

The artist insists that his sculptures be colorless, in contrast to the images scientists sometimes disseminate that are enhanced with bright hues. “Viruses have no color as they are smaller than the wavelength of light,” says Jerram, in an email. “So the artworks are created as alternative representations of viruses to the artificially colored imagery we receive through the media.” Jerram and Davidson create sketches, which they then take to the glassblowers, to see whether the intricate structures of the diseases can be replicated in glass, at approximately one million times their original size.

These glass sculptures require extreme attention to detail. “I consult virologists at the University of Bristol about the details of each artwork,” says Jerram. “Often I’m asking a question about how a particular part of the virion looks, and they don’t know the answer. We have to piece together our understanding by comparing grainy electron microscope images with abstract chemical models and existing diagrams.”

Yet, to physically create these structures in glass, the design may have to be tweaked. Some viruses, in their true form, would simply be too delicate and wouldn’t hold up. Jerram’s representation of the H1N1 (or Swine Flu) virus, for instance, looks far spikier than it might in reality. This was done, not to add to the ferocity of the virus’ image, but to prevent the artwork from crumbling or breaking.

Jerram has to decide what to do when new research suggests different forms for the structures of viruses. “Over time, scientific understanding of the virus improves and so I have to amend my models accordingly,” explains the artist. For example, “I’m currently in dialogue with a scientist at the University of Florida about the structure of the smallpox virus. He has published papers that show a very different understanding of the internal structure. I now need to consider whether to create a new model or wait until his model has become more widely accepted by the scientific community.” Jerram’s art is often used in scientific journals as an alternative to colorful simulations, so being as up-to-date as possible is definitely in his best interest.

Jerram’s marvelous glass sculptures bring awareness to some of the worst killers of our age. “The pieces are made for people to contemplate the global impact of each disease,” he says. “I’m interested in sharing the tension that has arisen between the artworks’ beauty and what they represent.”

Jerram’s microbial sculptures are on display in “Playing with Fire: 50 Years of Contemporary Glass,” an exhibition at New York’s Museum of Art and Design through April 7, 2013, and “Pulse: Art and Medicine,” opening at Strathmore Fine Art in Bethesda, Maryland, on February 16. “Pulse” runs through April 13, 2013.

Editor’s Note, February 15, 2013: Earlier versions of this post incorrectly stated or implied that E. coli and malaria are viruses. They are not–E. coli is a bacteria and malaria is a malaise caused by microorganisms. Errors in the first paragraph were fixed and the title of the post was changed.