The Gorgeous Shapes of Sea Butterflies

Cornelia Kavanagh’s sculptures magnify tiny sea butterflies—ocean acidification’s unlikely mascots—hundreds of times

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130916114019LH5_Front_0261-470.jpg)

Ocean acidification has taken up an unlikely mascot: the shelled pteropod. While “charismatic megafauna,” the large creatures that pull at our heartstrings, are typically the face of environmental problems—think polar bears on a shrinking iceberg and oil-slicked pelicans—these tiny sea snails couldn’t be more different. They don’t have visible eyes or anything resembling a face, diminishing their cute factor. They can barely be seen with the human eye, rarely reaching one centimeter in length. And the changes acidification has on them are even harder to see: the slow disintegration of their calcium carbonate shells.

Even without the threat of more acidic seas—caused by carbon dioxide dissolving into seawater—pteropods (also called sea butterflies) look fragile, as if their translucent shells could barely hold up against the rough ocean. This fragility is what attracted artist Cornelia Kavanagh to sculpt the miniscule animals. Her series, called “Fragile Beauty: The Art & Science of Sea Butterflies,” will be on display at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Sant Ocean Hall starting September 17.

“By making visible that which is essentially invisible, my pteropod sculptures could dramatize the threat of ocean acidification in a refreshing new way, causing the pteropod to become a surrogate for a problem of far-reaching implications,” says Kavanagh.

A sculpture of the pteropod Limacina retroversa shows the effects of acidification with a thinning shell and downturned “wings.” Photo Credit: John Gould Bessler

Ocean acidification is expected to affect a panoply of ocean organisms, but shelled animals like corals, clams and pteropods may be hardest hit. This is because the animals have more trouble crafting the molecular building blocks they use to construct their shells in more acidic water.

Pteropods and other shelled animals that live near the poles have an even bigger challenge: they live in cold water, which is historically more acidic than warm water. Acidification is expected to hit animals in colder regions first and harder—and it already has. Just last year, scientists described pteropod shells dissolving in the Southern Ocean off the coast of Antarctica. These animals aren’t just struggling to build their shells; the more acidic water is breaking their shells apart.

While Kavanagh’s sculptures were made before this discovery, she still tried to portray the future effects of acidification by sculpting several species of pteropod in various stages of decay. Some of her pteropods are healthy, with whole shells and “wings”—actually the snail’s foot adapted to flap in the water—outspread. Others have holes in their shells with folded wings, so the viewer can almost see them sinking to the seafloor, defeated.

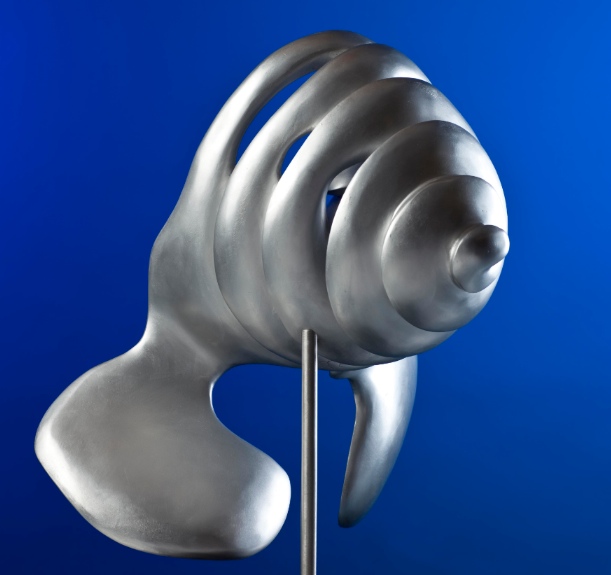

The body form of pteropods (here, Limacina helicina) reminded Kavanagh of her artistic inspirations: Modernist artists such as Miro, Arp and Kandinsky. Photo Credit: John Gould Bessler

Before starting this project, Kavanagh had never heard of pteropods. She wanted to make art reflecting the impacts of climate change, and was searching for an animal with an appealing shape for abstraction. One day she stumbled upon the image of a pteropod and was sold. She found the animals both beautiful and evocative of the work of Modernist artists she admires, such as Miro, Arp and Kandinsky.

She based her aluminum and bronze sculptures off of pictures she found in books and on the internet, blown up more than 400 times their real size. But when she finished sculpting, she panicked. “While I tried to symbolize the danger pteropods faced by interpreting their forms,” Kavanagh says, “I became increasingly concerned that my sculptures might be too abstract to be recognizable.”

A pteropod (Limacina helicina) sculpture from Cornelia Kavanagh’s exhibition, which opens this week at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Sant Ocean Hall. Photo Credit: John Gould Bessler

She contacted Gareth Lawson, a biological oceanographer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who studies the impacts of acidification on pteropods. To her relief, when he looked at pictures of her sculptures, he was able to easily identify each down to the species. After that, the pair teamed up, writing a book together and curating a show in New York, called “Charismatic Microfauna,” with scientific information alongside the sculptures.

“What drew me to work in particular is the way in which, through their posture and form, as a series her sculptures illustrate pteropods increasingly affected by ocean acidification,” says Lawson. “Through her medium she is ‘hypothesizing’ how these animals will respond to the changed chemistry of the future ocean. And that’s exactly what my collaborators and I do, albeit through science.”

Learn more about ocean acidification and see more ocean art at the Smithsonian’s Ocean Portal.

Learn more about ocean acidification and see more ocean art at the Smithsonian’s Ocean Portal.