Seeing Pictures of Home Can Make It Harder To Speak a Foreign Language

Being exposed to faces or images that you associate with your home country primes you to think in your native tongue, a new study shows

![]()

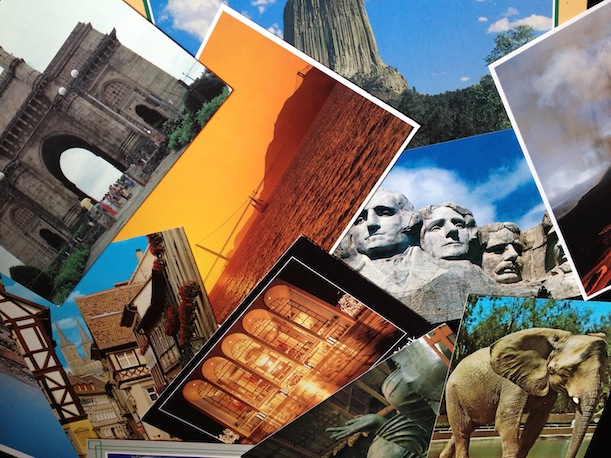

Being exposed to faces or images that you associate with your home country primes you to think in your native tongue, a new study shows. Photo by Mohi Kumar

If you’ve ever attempted to move to a foreign country and learn to speak the local language, you’re aware that successfully doing so is an enormous challenge.

But in our age of widely distributed Wi-Fi hotspots, free Skype video calls from one hemisphere to another and favorite TV shows available anywhere in the world over the web, speaking a foreign language may be more difficult than ever.

That’s because, as new research shows, merely seeing faces and images that you associate with home could make speaking in a foreign tongue more difficult. In a study published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from Columbia University and Singapore Management University found that for Chinese students who’d recently moved to the U.S., seeing several different types of China-related visual cues measurably reduced their fluency in English.

In the first part of the study, the researchers tested 42 students’ English speaking ability under two different circumstances—while looking at a computer screen, they either spoke with an image of a Caucasian face or a Chinese one. In both cases, they heard the exact same prerecorded passage (about the experience of living on a college campus) and responded with their own thoughts in English.

When the students conversed with the image of a Chinese person, they spoke more slowly and with slightly less fluency, as judged by an observer that was unaware of which image they’d been looking at. As a control, the researchers also tested a group of native English speakers’ fluency when speaking with both images, and found no difference.

In the second part, instead of looking at a face, 23 other students viewed quintessential icons of Americana (Mt. Rushmore, for example) or icons of Chinese culture (such as the Great Wall) and then were asked to describe the image in English. Once again, looking at the Chinese-related images led to reduced fluency and word speed.

Finally, in the last part of the experiment, the researchers examined particular objects with names that can be tricky to translate from Chinese to English. The Chinese word for pistachio, for example, translates literally as “happy nut,” while the word for lollipop translates as “stick candy,” and the researchers wanted to see how prone to using these sorts of original Chinese linguistic structure the students would be under various conditions. (For an English example, think of the word “watermelon”—you wouldn’t translate into other languages by combining that language’s word for “water” with the word for “melon.”)

The researchers showed photos of these sorts of objects to 85 Chinese-speaking students who’d only been in the country for about 3 months. Some students saw familiar images from Chinese culture, while others saw American or neutral images. All groups demonstrated the same level of accuracy in describing objects like pistachios, but they proved to be much more likely to make incorrect overly literal translations (calling pistachios, for example, “happy nuts”) when shown Chinese imagery first than with either of the other two categories.

The researchers explain the results as an example of “frame-switching.” In essence, for the native Chinese speakers still learning English as a second language, being exposed to faces or images that they associated with China unconsciously primed them to think in a Chinese frame of reference. As a result, it took more effort to speak English—causing them to speak more slowly—and perhaps made them more likely to “think in” Chinese too, using literal Chinese linguistic structures instead of translating into the correct English words.

All this could eventually have some impact on the practices surrounding the teaching of second languages, providing further evidence that immersion is the most effective way for someone to gain mastery because it reduces the sort of counter-priming examined in this study. If you’ve recently immigrated to place where your native tongue isn’t widely spoken or you’re living abroad for an extended period of time, there’s a lesson here for you too: If you want to become fluent in the language around you, keep the video calls and TV shows from home to a minimum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)