Scientists Discover the Genetic Reason Why Birds Don’t Have Penises

Developing bird embryos do have penis precursors, it turns out, but a genetic signal causes the penis cells to die off during gestation

![]()

Developing bird embryos do have penis precursors, it turns out, but a genetic signal causes the penis cells to die off during gestation. Image via Wikimedia Commons/Habib M’henni

Take a close look at nearly any male land bird—say, a rooster, hawk or even a bald eagle—and you’ll notice that they lack something present in most male animals that have sex via internal fertilization. Namely, a penis.

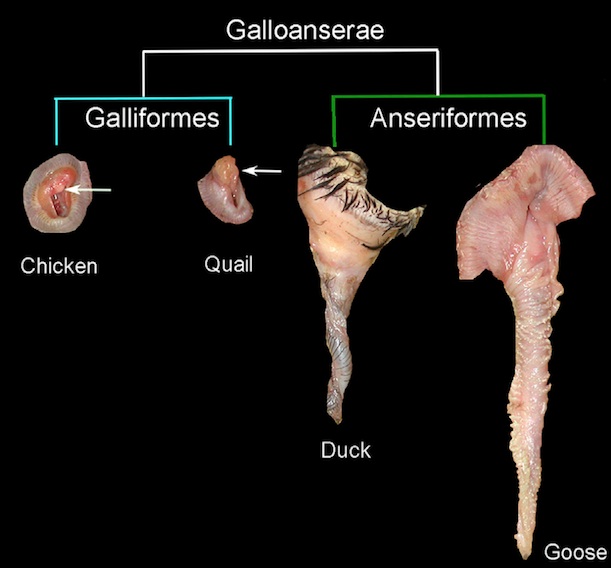

With a few exceptions (such as ostriches, ducks, and geese), male land fowl have no external sex organs. Instead of using a penis to fertilize a female’s eggs during mating, they eject sperm out of their cloaca—an orifice also used to excrete urine and feces—directly into the cloaca of a female (the maneuver is known by the touchingly romantic name “cloacal kiss”).

The evolutionary reason why these birds don’t have penises remains a mystery. But new research has finally shed light on the genetic factors that prevent male land birds from growing penises as they mature.

As described in an article published today in Current Biology, researchers from the University of Florida and elsewhere determined that most types of land fowl actually do have penises while in an early embryonic state. Then, as they develop, a gene called Bmp4 triggers a cascade of chemical signals that causes the cells in the developing penis to die off and wither away.

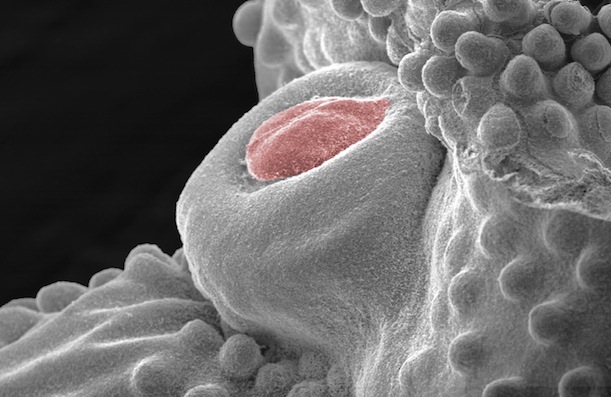

The team, led by Martin Cohn and graduate student Anna Herrera, compared the embryonic development of two types of land birds that lack penises (chickens and quail) with two species of waterfowl that have coiled penises that can be elongated (geese and ducks). Using an electron microscope, they found that in the early stages of development, male embryos from both of these groups had penis precursors.

An electron microscope of the developing penis in a chicken embryo (shown in pink), before the Bmp4 gene activates and causes its cells to die. Image via A.M. Herrera and M.J. Cohn, University of Florida

But soon afterward, for the chickens and quail, the Bmp4 gene activates in the cells at the tips of the developing penises. This gene triggers the synthesis of a particular protein called Bmp4 (bone morphogenetic protein 4), which leads to the controlled death of the cells in this area. As the rest of the bird embryo develops, the penis shrinks away, ultimately producing the modest proto-phallus found on the birds as adults.

To confirm the role of the Bmp4 gene, the researchers artificially blocked the chemical signaling pathway through which it triggers cell death, and found that the chicken embryos went on to develop full-fledged penises. Additionally, the researchers performed the opposite experiment with duck embryos, artificially activating the Bmp4 signal in the cells at the tip of the developing penis, and found that doing so caused the penis to stop growing and whither away as it usually does in chickens.

Most male birds, including chicken and quail, have no penises, but ducks and geese have coiled penises that can measure up to 9 inches in length. These retract when not in use. Image via Current Biology/Herrera et. al.

Knowing the genetics behind these birds’ lack of penises doesn’t explain what evolutionary benefit it might confer, but the researchers do have some ideas. Male ducks, for instance, are notorious for having sex with females by force; by contrast, the fact that most land birds have no penis means that females have more control over their reproductive destiny. This could theoretically allow them to be more choosy over their mates, and select higher quality males overall.

Of course, all this might make you wonder: Is there really a point to studying the missing penises of birds? Well, as noted after the brouhaha that erupted a few months ago over federally-funded research into duck penises, research into seemingly esoteric aspects of the biological world—and, really, the natural world as a whole—can provide very real benefits to humanity in the long-term.

In this case, a better understanding of the genetics and chemical signals responsible for the development of the organ could have applications that stretch much farther than even the duck’s penis. Many of the particulars of embryonic development—including the Bmp4 gene and associated protein—are highly conserved, evolutionarily, meaning that they’re shared between many diverse species, including both birds and humans. So researching the embryonic development of even animals that are only distantly related to us, like birds, could one day help us better understand what goes on when human fetuses are in the womb and perhaps enable us to address congenital defects and other deformities.

And if that doesn’t do it for you, there’s also just the astounding weirdness of watching duck penises unfurl in slow motion. Brace yourself:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)