Prehistoric Pointillism? Long Before Seurat, Ancient Artists Chiseled Mammoths Out of Dots

Newly discovered 38,000-year-old cave art predates the French post-Impressionist art form

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c8/89/c88916ba-5a82-4fd2-b24b-3a939c9e3016/pointillism-v2_720.jpg)

Almost 100 years ago, archaeologists were hard at work tearing up the ground at Abri Blanchard and Abri Cellier, two archaeological sites in Dordogne, France. Sometimes using explosives to aid in their work, these amateur explorers scoured the cave-filled region to come up with numerous engravings and paintings made by some of our earliest ancestors to settle modern Europe. The two sites quickly became known as treasure troves of early human habitations—think cave paintings like those in Lascaux—and were thoroughly picked over.

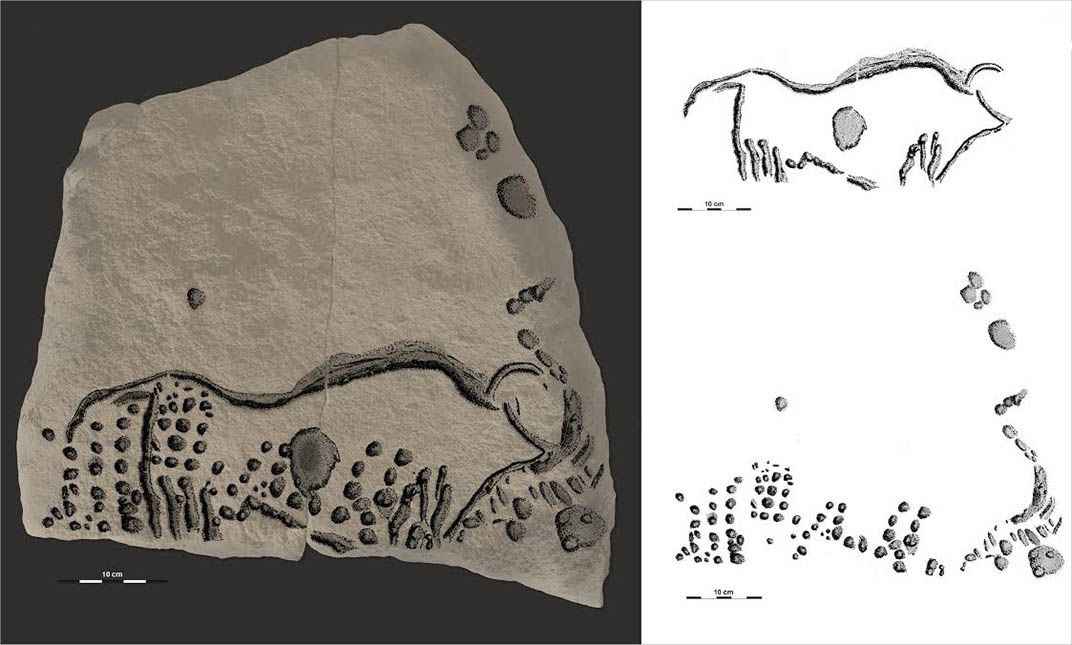

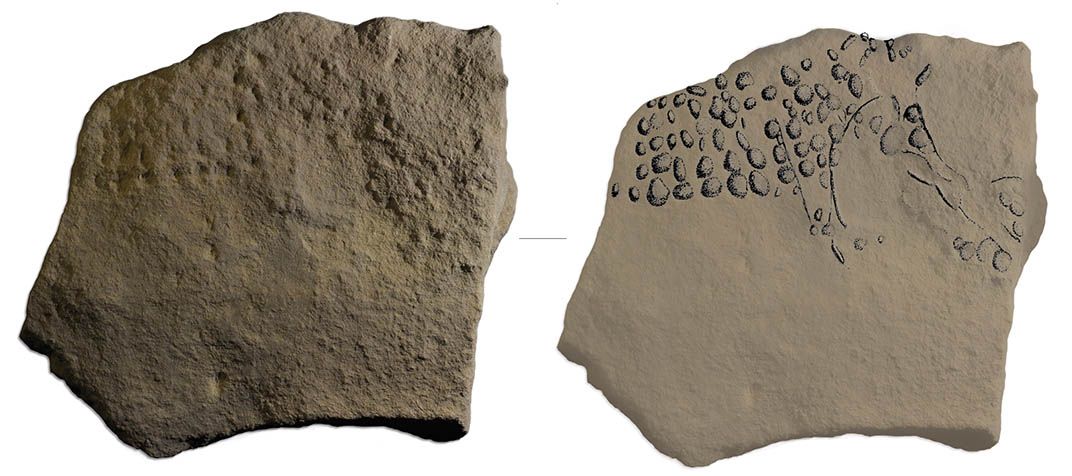

So when Randall White and a team of researchers visited Abri Blanchard in 2012 and Abri Cellier in 2014, they didn’t have high hopes of finding anything undisturbed. When they found a large pile of limestone blocks stacked at Abri Cellier, for instance, it seemed like just another pile of unremarkable materials that the early archaeologists had disrupted without thoroughly examining and documenting. Then they realized the rocks were covered in markings. Chiseled into one of the stones were rows of dots that formed a striking pattern: a woolly mammoth.

“You actually see the hand of people from 38,000 years ago. Who wouldn’t be moved by it?” says Randall White, a professor of anthropology at New York University and one of the authors of a study published last Friday in the journal Quaternary International.

White’s team had recently found an image made with a similar technique at Abri Blanchard earlier, so they already suspected that what they had on their hands was made by humans. But to be certain, they used microscopic analysis to look at surface abrasions to confirm the patterns matched human-created marks rather than marks left by nature. From there it was easy to—shall we say—connect the dots to figure out that the mammoth was the product of an unknown member of the Aurignacian people, named for the French village Aurignac.

Approximately 40,000 years ago, when Europe was still largely blanketed in snow, ice and glaciers from the Würm glaciation, the Aurignacians became the first modern humans to arrive in Western Europe, where Neanderthals had already settled. For millennia, the Aurignacians survived in rocky shelters in in France, Germany, Spain and elsewhere, benefitting from milder microclimates in those regions. They hunted game and likely saw the migration of numerous herds along the nearby river valley: mammoths, horses, aurochs (large, wild cattle) and others.

Most remarkably to those like White who study ancient human civilizations, the Aurignacians pulled inspiration from the world around them to create art. Decorated beads, clay figurines like the Venus of Willendorf, and hundreds of paintings and etchings in their rocky shelters.

“What makes the art so incredibly cool is the fact that the Aurignacians were a graphic society already. It tells us, in a general sense, that they had very modern minds,” says Genevieve von Petzinger, an archaeologist and the author of The First Signs: Unlocking the Mysteries of the World’s Oldest Symbols.

That affinity with modern humans can also be misleading, says White. “You feel very close, and at the same time very distant,” he says. “They had their own culture and we have our own culture. There’s always a gap … I’m not sure I’m anywhere close to understanding the significance of that image for their lives.”

What we do know is that the prehistoric pointillist technique must have been a labor-intensive process, White says. The artists would have rubbed down the surface of the stone slab with a harder stone, like quartzite, until the surface was smooth. Then they used another tool to create a cupule, a cup mark that looks like the hollowed-out dots on a domino piece. In the case of the woolly mammoth, the engraver made more than 60 individual punctuations and then altered the edge of the rock by grinding it away to make a notch for the neck.

“They essentially built the mammoth into the adapted corner,” White says. He estimates the entire process took around 2 hours.

The style is especially striking because it’s now been found not only at Abri Cellier and Abri Blanchard, but also in a pointillist rhinoceros painted on the walls of the Chauvet caves nearly 250 miles away. In the case of the rhinoceros, the image was made by applying paint to the palm of the hand, then pressing the circular smudge into the wall repeatedly, until a figure emerged, says French archaeologist and chemist Emilie Chalmin-Aljanabi. Based on the paints they created, these early humans must have been “excellent mineralogists,” she adds.

But don’t go too dotty about this instance of prehistoric pointillism, art experts caution. Using the term “pointillist” to describe the engravings and paintings might be stretching the definition of the French post-Impressionist artistic technique, says Gloria Groom, the director of European painting and sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago.

“I don’t think you can say they were striving for abstraction,” Groom says of pointillist artists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who invented the technique in 1886. “It was about the way colors can be laid on canvas to maximize the sense of light. What’s behind pointillism is divisionism, the new scientific theories of light and color and ocular perception.” Pointillism was also very precise, Groom says; many of Seurat’s paintings started out as sketches, then drawings on grids before the final composition. Seurat drew on his background as a draftsman to achieve this technical precision.

Yet the new artistic discoveries made at Abri Blanchard are certainly significant to our understanding of how art evolved and functioned in prehistoric times. With the new discoveries made at Abri Blanchard, the number of artistically modified blocks has jumped from 88 to 147 across the nine Aurignacian rock shelter sites.

“Some of these sites were excavated so early, people feel like, it’s already been done,” says von Petzinger, who admits to getting very excited about “rows of dots.” “I think it’s really exciting that Randy and his team are revisiting these sites. Little did we know what was sitting right under our noses.”

This kind of find could help archaeologists ask more pointed questions about the spread of culture across Paleolithic societies she adds.

“For a 30,000 year period, we only have about 400 sites,” says von Petzinger. “To be finding these same techniques fairly widespread in use makes us wonder about whether there were common cultures back then. Were they staying in touch? Are they techniques developed in Europe, or even earlier? That’s what’s so exciting about the Aurignacian time period. The more we realize how well-established art traditions already were, the more we can ask how long ago they started.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)