Mapping the Art Genome

A new Web site called Art.sy recommends art based on a visitor’s preference for a particular artist or artwork

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121101125755art-gallery-web.jpg)

I think we can all agree that artists inherit styles and techniques from their predecessors. After all, artists have grown accustomed to talking about their “influences.” Generally, they can string together genealogies, tracing their artistic lineages from famous artists of the past to schools of like-minded artists working today.

But what would you say if all of this hereditary information floating around the art world was likened to a genome?

This is exactly what business partners Carter Cleveland and Sebastian Cwilich have done with Art.sy, a new Web site that the duo launched just this week. The site is an impressive library of more than 17,000 images of artwork by some 3,000 artists—all supplied by museums, galleries, institutions and private collections from around the world. The start-up company is billing the site as the Pandora of fine art.

If you’re not familiar, Pandora is a Web site that takes a visitor’s preference for an individual musician or song and creates a personalized radio station to fit his or her taste. If you like the Beatles’ “Paperback Writer,” you may also like “Ruby Tuesday” by The Rolling Stones, for instance, or “I Can’t Explain” by The Who.

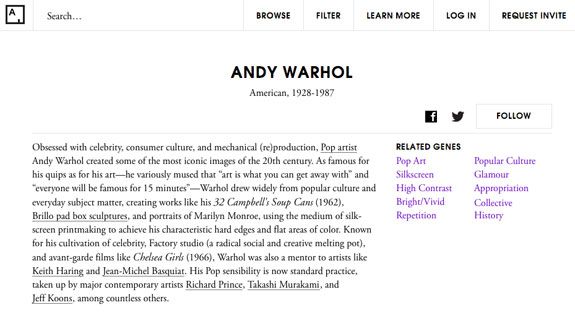

With Art.sy, a visitor can enter an artist, artwork, artistic movement or medium into a search bar and the site will generate a list of artists and works that have been deemed related in some way. “There are a lot of people who may know who Warhol is, but they have no idea who Ray Johnson is. The ability to make those connections is what this is about,” said Cwilich, Art.sy’s Chief Operating Officer, on a recent segment of The Takeaway with John Hockenberry.

The endeavor is a true collaboration between computer scientists and art historians. (This is even evident in Art.sy’s leadership. Cleveland, Art.sy’s 25-year-old chief executive officer, is a computer science engineer, and Cwilich is a former executive from Christie’s Auction House.) To create a Web site that could generate fine-art recommendations, the Art.sy team had to first tackle the Art Genome Project. Essentially, a number of art historians have identified 800-and-counting “genes,” or characteristics, that apply to different pieces of art. These genes are words that describe the medium being used, the artistic style or movement, a concept (i.e., war), content, techniques and geographic regions, among other things. All the images that are tagged with a specific gene—say, “American Realism” or “Isolation/Alienation”—are then linked within the search technology.

Matthew Israel, the director of the Art Genome Project, explained the process at the DataGotham conference at New York University last month. Using Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Diptych as an example, he said that the genes attributed to the work might include “painting,” “pop art,” “silkscreen,” “high contrast,” “repetition,” “grid,” “glamour” and “United States.” With this foundation in place, Art.sy is able to take an artist, chosen by a visitor to the site, and then create a list of artists with similar “genes.” For a given work of art, the site can also retrieve other individual works of art that express similar traits.

In his presentation, Israel described Art.sy as being like “those teachers that are really good at riffing in a lecture.” Some of the parallels that the site draws between artists are ones that art historians would naturally make, whereas others are welcome surprises. In the Takeaway radio interview, Cleveland shared an interesting example. A search he had done of Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring turned up some likely “related” suspects—paintings by Dutch and Flemish Old Masters, such as Rubens and Rembrandt. However, it also churned up a contemporary work by John Currin titled The Pillow, which is similar in that it is also a close-up of a woman’s face. “That is just a really interesting example of a connection that transcends both geography and time,” said Cleveland, on the show. “I often find that connections like that are the most satisfying.”

Some artists, on the other hand, have been befuddled by who Art.sy considers their “distant relatives.” In June, TIME magazine reported:

Another problem Art.sy faces is its classification system, which rubs some artists the wrong way. “I don’t think what I am doing has anything to do with Cindy Sherman,” says British artist Jonathan Smith after being told the site links his work to hers via a staged-photography gene. “That sounds like something a programmer would think of.”

And, a few art historians are a bit turned off by the way the site has sort of mechanized art analysis. A New York Times article from earlier this week reads:

Robert Storr, dean of the Yale University School of Art, has his doubts. “It depends so much on the information, who’s doing the selection, what the criteria are and what the cultural assumptions behind those criteria are,” Mr. Storr, a former curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, said. In terms of art comprehension, he added, “I’m sure it will be reductive.”

In Art.sy’s defense, Cwilich noted on the Takeaway, “Any exercise like this has to be undertaken with a great degree of humility and an acknowledgement that it is very subjective. But the goal is not to reduce the artwork but rather to help people discover new things.”

As one of Art.sy’s partner institutions, the Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum has contributed images of about 1,600 of its artifacts. Many of the drawings and prints by known artists are accessible on the site. The Manhattan museum is particularly grateful for this means of sharing its collection with the public, as it is closed for renovation until 2014.

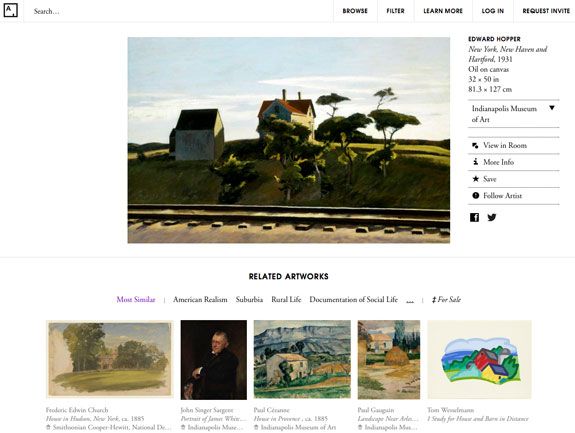

Sebastian Chan, the Cooper-Hewitt’s director of digital and emerging media, has been putting the site through its paces. “We’ve been looking to see which images come up with our own ones, and generally the results have been good,” says Chan, in an email. “I don’t see Art.sy as providing ‘exact matches’ but rather providing a ‘serendipity engine,’ which improves the ability for users to explore without necessarily knowing exactly what they are looking for.”

Chan compares Art.sy to a traditional museum visit. “When visitors walk in the door of a museum, they are there to explore, get happily lost and immerse themselves in works they didn’t know they were interested in,” he says. “That sense of being ‘happily lost’ is very difficult to design for in traditional museum Web sites, which have been modeled on librarian-style ‘search’ and aimed at ‘scholars.’” But Art.sy, Google Art Project and even the Cooper-Hewitt’s Alpha Collection Online are attempting it.

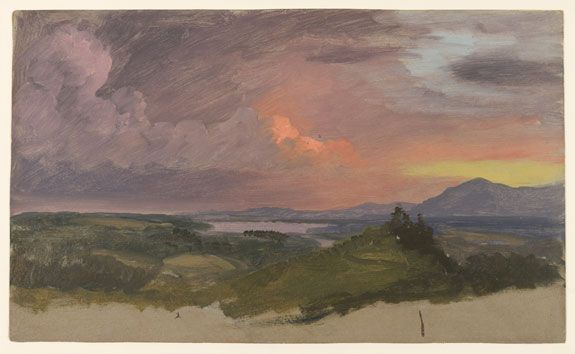

In his own explorations on Art.sy, Chan found that Thomas Moran’s Grand Canyon in Stormy Weather, Arizona, from the Cooper-Hewitt’s collection, has some similar colors and patterns as works by artist Ed Ruscha. He also discovered that Frederic Edwin Church’s Sunset in the Hudson Valley can be compared to pieces from the Walters Art Museum, Indianapolis Museum of Art and the Yale Center for British Art.

“Art.sy offers an interesting opportunity for us to see how our collection meshes with those of other institutions,” says Chan.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)