How Do You Make Beer in Space?

Strap on your beer goggles and join us on a hops-fueled rocket ride

:focal(2100x2312:2101x2313)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/2e/e02e3c99-18a4-460c-9c74-4e16f26d721c/apr2018_h08_futureofbeer.jpg)

There is no pie in the sky.

There’s no beer, either.

In 2007, following confirmation that two of its astronauts had flown three sheets to the ozone, NASA formally banned crews from imbibing in orbit. These days any rocketeer wishing to get staggeringly pie-eyed and maybe moon the Moon will have to hitch a ride with another space agency altogether.

It’s equally sobering to note that carbonated beverages are outlawed on the International Space Station. Gas bubbles in a carbonated drink don’t act the same as on gravity-rich Earth. Instead of floating to the top, the bubbles lie there, evenly distributed in the liquid. Maybe that’s just as well. The drink would be a frothy mess. To rework the lyrics of David Bowie’s “Space Oddity,” the head on a brewski poured from a tin can far above the world would float in a most peculiar way. How peculiar? Tristan Stephenson, author of The Curious Bartender, has speculated that the bubbles in this slop would “flocculate together into frogspawn-style clumps.”

Frogspawn would make a great craft beer name, if it isn’t one already. And though weightlessness might make falling off one’s bar stool safer, as the British magazine New Scientist once delightfully explained, “without gravity to draw liquids to the bottoms of their stomachs, leaving gases at the top, astronauts tend to produce wet burps.” It ain’t easy to belch in outer space.

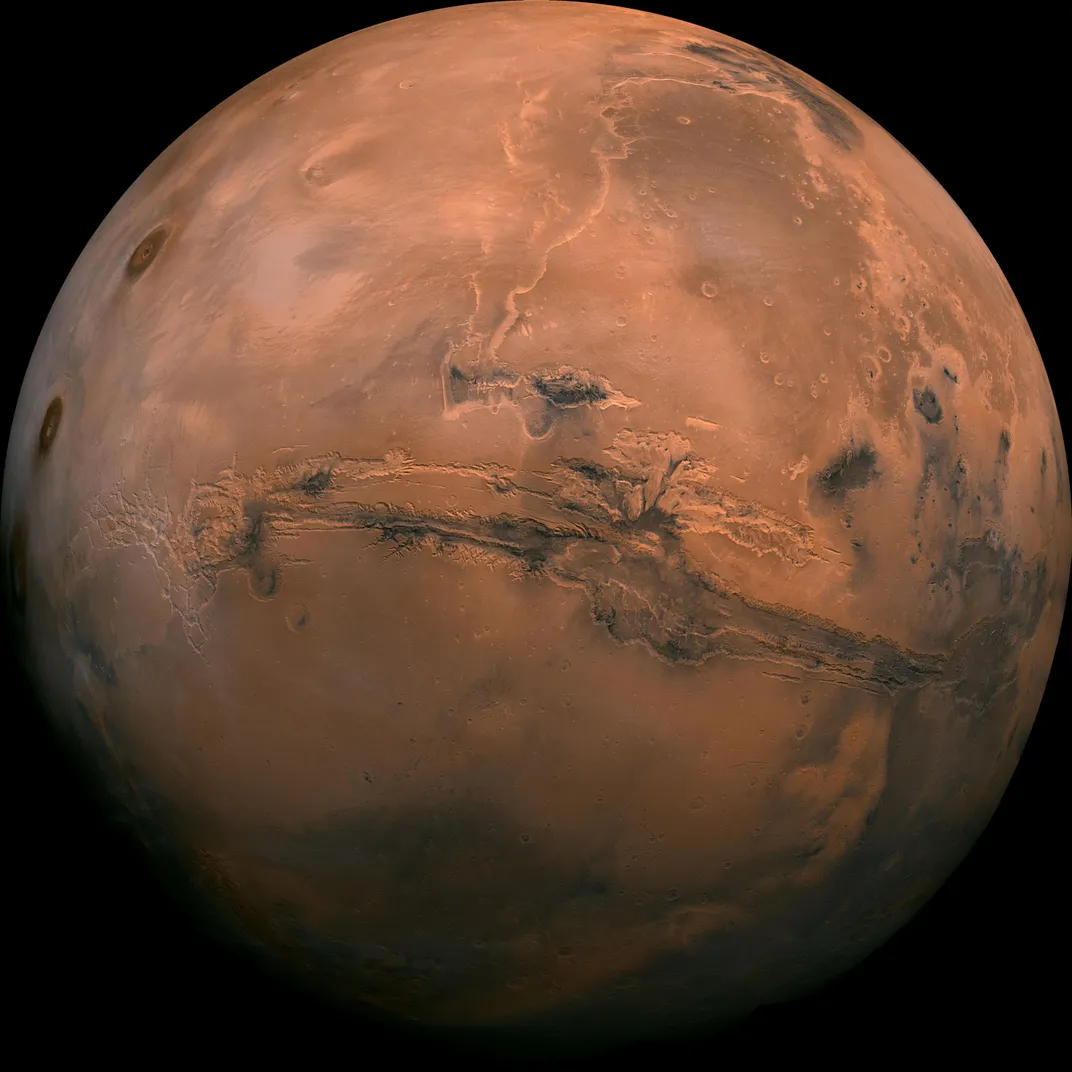

All this hasn’t stopped the typographical Frankenstein known as Anheuser-Busch InBev from devising plans to boldly brew where no man has brewed before. Last December, as part of the macrobrewery’s microgravity research, the makers of Budweiser had Elon Musk’s SpaceX rocket transport 20 barley seeds to the ISS. Mindful of NASA’s long-term goal to send humans to Mars by the 2030s, space station scientists conducted two 30-day experiments, one on seed exposure and the other on barley germination. In a statement, Bud announced that its long-term goal is to become the first beer of the red planet.

It’s a well-known fact that water, a basic component of beer, is in short supply outside of Earth. But satellite imaging has confirmed that vast glaciers of ice exist below Mars’ rocky surface. “Several universities are working on mining and mining technology for Mars, including mining water,” says Gary Hanning, who heads Budweiser’s innovation and barley research team in Fort Collins, Colorado. “The miners will have to bring out the ice, thaw it, clarify it, purify it and all those other good things. But it’s still going to be an extraordinarily limited raw material.” Houston, we have a drinking problem.

We all know that Budweiser travels well, but...49 million miles! According to NASA, shipping costs to space can run about $10,000 a pound. “The cost per gallon of beer is going to be outrageous,” Hanning concedes. “We’re going to want to produce our own food and crops and products there, and not haul them back and forth all the time.” It’s been argued that you can’t really enjoy a cold one when the temperature outside is minus 195 degrees, and that beer crops won’t grow in a place inhabited only by sand and iron dust. “Argued by whom?” asks Steve Rushin, author of the witty, beer-centric novel The Pint Man. “Those are the kind of arguments you have on Earth, in a bar, after one too many.”

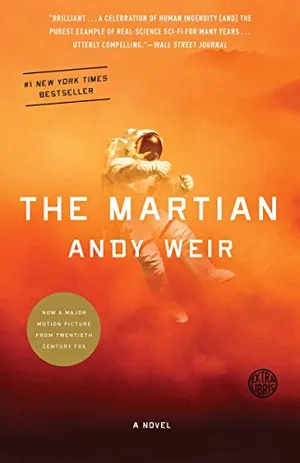

In the blue planet’s taprooms, Budweiser’s extraterrestrial dilly-dillying has raised a star-fleet of existential questions. If Matt Damon could live off potatoes grown in his own poop in The Martian, could Mars colonists live off Bud? Would self-driven Mars rovers eliminate the need for designated drivers? Will robot beers be made by robots, or consumed by them? And, at a time when the names of small-batch brands are becoming increasingly otherworldly (Space Cake, Black Hole Sun, Totally Wicked Nebula, Klingon Ale), what are beers’ final frontiers?

The Martian

After a dust storm nearly kills him and forces his crew to evacuate while thinking him dead, Mark finds himself stranded and completely alone with no way to even signal Earth that he’s alive—and even if he could get word out, his supplies would be gone long before a rescue could arrive.

A cynic might say the reason Budweiser is trying to stake out territory on the fourth rock from the Sun is that its turf on the third is slowly shrinking. Last year, for the first time in decades, Bud was not among the top three best-selling beers in America. Sales have slumped for all industrial-scale brews, due in no small part to the rapid fermentation of craft beers.

Beer geekerati have long disparaged the conglomerate’s brews as watery and flavor-challenged while championing traditional, local tipples. The intense infusions (blood orange, ghost peppers), esoteric additives (stag semen, crushed lunar meteorites) and sometimes preposterous ingredients (yeast grown in a brewmaster’s beard, coffee beans predigested by elephants) supposedly lead to more complex flavors than the beer majors can provide. Even Elvis—and perhaps only Elvis—might have been tempted by Voodoo Doughnut Chocolate, Peanut Butter & Banana Ale.

Steve Rushin predicts beer is fated to become even more locavore-ish (locavore-acious?) than it is now. “In the future you’ll choose from beers brewed in your own neighborhood, possibly your own street, maybe your own house,” he says. “You may already be living in this future.”

For its part, Budweiser seems to be living in the future of Total Recall, a 1990 sci-fi thriller that envisioned what bar service on Mars will look like in 2084 (neon Coors Light and Miller Lite signs, and not a craft beer in sight). Asked if he’s distressed that the first beer poured on Mars may be a pedestrian Bud, James Watt, co-founder of the Scottish “punk” beer company BrewDog, growls: “It’s not so bad if it means it leaves this planet.” Despite the King of Beers’ plans for interplanetary conquest, Watt doubts it will one day become the King of Galactic Beers. “You can’t make much beer with 20 seeds of barley,” he says. “Call me when Bud is growing hops on Mars.”

**********

As it turns out, a group of students at Villanova University have done just that—more or less. A few months back, Edward Guinan had one of his classes experiment to see which terrestrial plants would thrive in the dense, cakey soil of Mars. “I ruled out Venus, a pressure cooker with sulfuric acid rain,” he recalls. “The average temperature is around 865 degrees: It would be like trying to grow stuff in a pizza oven.” He set out to approximate Martian dirt.

Most students who took part in Guinan’s Red Thumbs Mars Garden Project sowed practical, nutritious vegetables with the soil simulant they developed. But one—surprisingly, not a frat boy—picked hops, the blossoms that impart a bitter bite to beer at the outset of production. The moderate, almost diffident Guinan vetoed marijuana, perhaps on the theory that space travelers would already be high enough.

Seedlings were cut with vermiculite and cultivated in a small patch of the campus greenhouse. Since less than half as much sunlight falls on the surface of Mars as on Earth, a mesh screen was erected to partially blot it out. In the thin light and thick soil, the hops flourished, but the potatoes—a staple of Damon’s diet in The Martian—did not. “Hollywood!” mutters Guinan.

In his eyes, The Martian’s more unforgivable blooper pertained to perchlorate, a chemical compound that abounds in the Martian regolith. While perchlorates are toxic and interfere with the human body’s ability to absorb iodine, researchers have also found that combining perchlorates with iron oxides and hydrogen peroxide—both found on Mars’ surface—and irradiating it with UV light (as on Mars) greatly increases the toxicity. Inhaling or ingesting it can lead to thyroid problems and even death. Guinan says hops farmers on Mars will have to purge the poison from the soil before Budweiser’s Clydesdales draw ploughs through it. “Fortunately,” he says, “perchlorate is water-soluble; farmers could rinse it out of the soil.” Spoiler alert: Perchlorate seemed to have no effect on Damon’s character. “On the real Mars he would have died,” Guinan says with a shrug. “The filmmakers didn’t want audiences to know that little detail.”

So much for movie science.

**********

Earth’s first robo-beer is generated by a machine-learning algorithm in a repurposed East London railway arch. In this tiny space, an open-access “guerrilla brewery,” beer hobbyists pay a monthly fee to use the industry-standard kits, share tips with other members and flaunt their ingenuity. Rob McInerney surveys the DIY domain with a critical eye and a twitching nose. The co-creator of AI-brewed IntelligentX is looking at and sniffing ale simmering in a stainless steel tank.

The liquid is covered with creamy sand-colored foam, like toasted meringue on a vast juicy pie. “IntelligentX is beer that learns,” McInerney says, flatly. The archway is heady with a smell of hops and malt as pungent as a newly mowed field. “You drink more, you get less smart, but IntelligentX is going to get smarter.”

McInerney’s potable is brewed by Automated Brewing Intelligence (ABI), a program that develops recipes based on algorithms cranked out with the help of consumer feedback. ABI continually rewrites the brewing process by altering variables like bitterness, alcoholic content and level of carbonation. The algorithm can also change the percentage of grain, malt, hops and encoded wild-card ingredients like lime and grapefruit.

“ABI acquires information about beer-making in much the same way as humans,” says the 33-year-old McInerney, who completed his PhD in machine learning at the University of Oxford. “It starts by observing the recipes that human brewers devise, then, through experience, comes up with its own ideas.”

Previously, cans were stamped with a web address linked to a Facebook Messenger bot, which grilled imbibers about the beers they just sampled. Questions, which differ for each person who comes onto the platform, involve customer preference and flavor; answers are yes or no, while rankings are done on a scale of one to ten. Soon, says McInerney, users will be directed to the company’s website, where data will be fed directly into the algorithms and to gather feedback. Once harvested, the data is interpreted by the ABI engine and pinged back to a master brewer, who tweaks the recipe.

The four basic brews of IntelligentX—golden, amber, pale and black—have already been through dozens of iterations. McInerney plans to open-source every unique recipe created by its algorithm so that home brewers can recreate their favorites. “Suddenly, you’ve got a product that’s a culmination of people,” he says, “not just some sort of machine creating stuff.”

The area surrounding McInerney’s brewery looks nothing like the East End where, in the late 1920s, George Orwell lived in the abject poverty he recounted in Down and Out in Paris and London. But McInerney has his own Orwellian fantasy: an iPub in which the pints are hooked up to ABI, which records how quickly a patron has guzzled, at what temperature and the volume of beer left in the glass. “I believe the future is a place where AI augments the skills of humans,” he says. “IntelligentX uses AI to confer superhuman skills on brewers, enabling them to receive feedback faster than ever before.”

If the destiny of beer is ABI, Sam Calagione, the founder of Dogfish Head, a U.S. craft brewery, says the concept makes him uneasy. “If you’re just going off algorithms,” he says, “you’re not going to be able to innovate ahead of what’s currently available. The context of what people say they want has to be relevant to what they’ve already tried.”

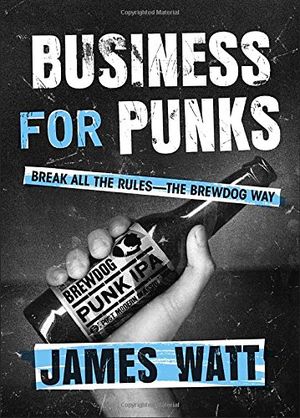

BrewDog’s James Watt agrees: “We love innovation in all aspects of what we’re doing—the amount you could learn from that level of automation is pretty crazy. But brewing for the majority is brewing for nobody in particular, and you’d end up with the lowest common denominator beer, which excites just as little as it offends. And that’s not worth sticking around for.”

**********

The World’s End is a pub in a 2013 British android-apocalypse film of the same name. It’s a place where you might have enjoyed drinking the End of History, a 110-proof Belgian ale released eight years ago by Watt’s brewery in Scotland. Only 12 bottles were made, and—to the outrage of animal rights activists—all were packed in taxidermied roadkill. “Beer pairs well with the apocalypse, for obvious reasons,” observes Steve Rushin. “If you’re the last man on earth, you’d probably want an End of History.”

In his manifesto Business for Punks: Break All the Rules—the BrewDog Way, Watt posits himself as the Johnny Rotten of beer-making. Like ye olde Sex Pistols singer, the brewer’s attitude tends to be edgy, willfully controversial and, in the extremity of its vision, directly political. Business for Punks counsels would-be entrepreneurs: “Don’t be a pathetic leech scrambling around for crumbs off someone else’s second-rate pie. Bake your own goddamn pie.”

Business for Punks: Break All the Rules--the BrewDog Way

James Watt started a rebellion against tasteless mass market beers by founding BrewDog, now one of the world’s best-known and fastest growing craft breweries, famous for beers, bars, and crowdfunding. In this smart, funny book, he shares his story and explains how you too can tear up the rule book and start a company on your own terms. It’s an anarchic, DIY guide to entrepreneurship—and a new manifesto for business.

Watt carefully curated BrewDog’s reputation as the provocateur of the craft beer revolution by staging brash stunts: launching the imperial-strength saison Make Earth Great Again in protest of the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris climate accord; provoking a trademark suit by the Presley estate by naming an IPA “Elvis Juice”; marking the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton by lacing a brew with Horny Goat Weed and christening it Royal Virility Performance.

Since establishing a beachhead in the North Sea port of Aberdeen nearly a decade ago, BrewDog has opened scores of wildly popular bars—bare brick, spray-painted graffiti—across the United Kingdom and around the world: Tokyo, Helsinki, Rome, São Paulo. Currently, the company is building The DogHouse, humanity’s first craft beer hotel-cum-sour brewery. Located in Columbus, Ohio—a long pub crawl from 16 colleges and universities—and next to BrewDog’s 100,000-square-foot brewhouse, the crowd-funded project will feature beer-infused breakfasts, lunches and dinners, with beers paired to every course. Amenities include hop-imbued massages.

The 32 rooms will feature Punk IPA taps and, in the showers, mini-fridges stocked with craft beers picked by Watt and BrewDog co-founder Martin Dickie. “We elected not to construct an outdoor swimming pool and fill it with beer,” says Tanisha Robinson, CEO of BrewDog USA. “I like my beer fresh and cold, not sweet. It’s not only kids who pee in pools.”

Robinson can’t decide whether the DogHouse is a hotel in a brewery or a brewery in a hotel. “It is the only fully immersive craft beer destination,” she says. “It could be the future of beer tourism.”

As Neil Armstrong might have put it: “That’s one small stout for man, one giant lager for mankind.”

A Toast to Outer Space

A brief history of extraterrestrial drinking.

1969

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/67/eb/67ebe562-ac4a-4064-a688-ba8e24e9106e/apr2018_h09_futureofbeer.jpg)

Buzz Aldrin, the aptly named Apollo 11 astronaut, takes communion in the hours before he and Armstrong embark on the first moonwalk. Wine and wafer are provided by Aldrin’s Webster Presbyterian church. He describes the lunar sacrament in his 2009 memoir Magnificent Desolation: “I poured a thimbleful of wine from a sealed plastic container into a small chalice, and waited for the wine to settle down as it swirled in the one-sixth Earth gravity of the moon.”

1994

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/a1/d2a1e704-1d03-4f04-b3b9-9397a57b02a0/apr2018_h10_futureofbeer.jpg)

Coors sponsors Kirsten Sterrett’s space shuttle experiment devised to test the effects of microgravity on fermentation. After the results are in, the University of Colorado grad student gives the space suds a “little taste.” The tiny sample isn’t really enough to savor, she says, “but why throw something like that away?”

1997

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/a3/6ca3c196-d1f6-41d2-9924-35052d8375ab/apr2018_h06_futureofbeer.jpg)

After a flash fire is extinguished aboard the Russian space station Mir, cosmonauts celebrate by breaking out their stashes of cognac. Though NASA forbids drinking in orbit, the Russians’ attitudes are a bit looser; Mir is supplied with French and Armenian brandy. Cognac was brought up on unmanned supply ships, and Russian ground control “winked at the practice,” according to American astronaut Jerry Linenger, who was aboard Mir at the time but declined to imbibe. “On board there is a little bit [of cognac],” acknowledged Mir’s commander, cosmonaut Vasily Tsibliyev. “It is needed because you can imagine the stressful

situation on board.”

2006

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/ee/66ee822f-3a88-41cd-a802-0cf612cb3e7f/apr2018_h05_futureofbeer-wr.jpg)

Japanese and Russian researchers send barley seeds to the International Space Station, to be planted in the Zvezda Service Module. After five months in the ionosphere, the grains are brought back to Earth, where Sapporo turns the fourth generation of those plants’ descendants into Space Barley, a six-pack of which fetched about $110. Yet more proof that what happens in space doesn’t stay in space.

2014

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/84/96/84961cdb-82dc-4bc7-8258-e0b53e81c2ff/apr2018_h07_futureofbeer.jpg)

Colorado sixth-grader Michal Bodzianowski builds and dispatches a mini-microbrewery (a tube jammed with hops, yeast, water and malted barley) to the ISS in 2013 to see how the ingredients interact. The next year, a civilian rocket carries up six strains of brewer’s yeast. Upon recovering the specimens, Oregon craft brewer Ninkasi steeps the payload in hazelnuts, star anise and cocoa nibs. The resulting imperial stout is dubbed Ground Control. It is now presumably Major Tom’s

favorite brew.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.