How a Deadly Flesh-Eating Fungus Helped Make Bats Cute Again

A silver lining to the worldwide epidemic of white nose syndrome: People like bats more now

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e8/e0/e8e0c712-dddc-42ae-ad7a-0452d5bd4be4/bat.jpg)

Let’s face it: Bats have an image problem. Since the time of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, these stealthy shadows have been tied up with images of the dark and demonic, of vampiric seduction, of blood-sucking and essence-drinking. They’ve been vilified as vectors for rabies and Ebola, deemed nighttime nuisances, and even inspired the very specific fear of one flying into your hair and getting stuck. “It’s hard to come across a bat in a non-terrifying situation,” says Amanda Bevan, urban bat project leader at the nonprofit Organization for Bat Conservation.

That’s a pity, because bats are wondrous. There are yellow bats and red bats, bats that slurp flowers and bats that drain cows, bats no bigger than a bumblebee and bats with wingspans longer than a person is tall. Bats that scarf down scorpions thanks to a honey badger-esque immunity to venom; bats that make their living swooping for fish off the coast of Mexico; and fruit bats in the forests of Indonesia whose males produce breastmilk.

In fact, despite their seeming elusiveness, bats comprise the second-most diverse group of mammals after rodents. One-fifth to one-quarter of all mammals are bats. Or, as Bevan puts it: “There are so many bats, and we know so little.”

From a human-centric point of view, many of these bats are also exceedingly useful. A 2011 study in Science estimated the economic value of bats to U.S. agriculture as being somewhere around $23 billion per year. In the same study, the researchers estimated that a colony of 150 big brown bats in Indiana ate nearly 1.3 million crop-devouring insects per year, and a million bats would consume 600 to 1,320 metric tons of insects per year. Even better, those insects included disease-carrying mosquitoes, flies and gnats.

“Bats are just secretly badass,” says Winifred Frick, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz who works with the nonprofit Bat Conservation International. “They’re not just this little animal that gets stuck in your attic and makes a mess.” She should know: her study subject is a species of desert bats in southwestern United States and Mexico that exclusively pollinates the agave plant—and thus enables the making of tequila. (You’re welcome.)

Unfortunately, our winged saviors face a grave danger. Since the winter of 2007, cave bats around the world have been falling prey to the existential menace of white nose syndrome, a fast-spreading fungus named for the white fuzz it forms on bats’ muzzles. This flesh-eating disease—which goes by the terrifyingly apt name of P. destructans—strikes bats while they lay dormant in hibernation. Once it infects its victim, the fungus weakens and starves the bat as it slumbers, eventually eroding its flesh and dissolving holes in its mouth, ears and wings. In the past decade, more than 6 million bats have died from white nose.

First identified in New York state in the winter of 2006, the disease has spread “at an alarming rate,” according to the U.S. Geological Society. In 2016, an infected, dying bat was found in Washington state. “It’s basically a race against time before it spreads across the country,” says Lindsay Rohrbaugh, a wildlife biologist with Washington, D.C.’s Department of Energy and Environment. “Now that it’s jumped over the Rocky Mountains, it’s a definite emergency. I think the western states thought they had some time to talk and plan how to deal with, but now there’s this sense of urgency: what do we do now?”

Two North American bat species—the gray bat and the Indiana bat—have recently found themselves on the national endangered species list thanks to the disease. Another, the Northern long-eared bat, is considered threatened.

For devoted bat scientists, watching the contagion spread has been devastating. Rohrbaugh, who has been working with bats in the D.C. area since 2012, has seen victims with holes in their wings, eaten away by the fungus. But the carnage has a silver lining. From a public awareness standpoint, the plight of bats worldwide may have finally given bats the PR boost they needed to shake their long-held stigma. As people realize how crucial bats are to their health, their surroundings and the economy, they're beginning to embrace bats as the charismatic creatures they’ve always secretly been.

In the UK, it’s practically a national pastime to go out on bat walks; recently, there was even the first bat walk organized by the deaf community. But in the U.S., urban bat walks and other bat appreciation events haven’t yet taken off in the same way as, say, birding. Leading the charge to turn around bats’ image problem are Frick’s and Bevan’s groups and the recently initiated Urban Bat Project, which is working to start bat walks in urban areas across the country from New York to D.C. to Michigan.

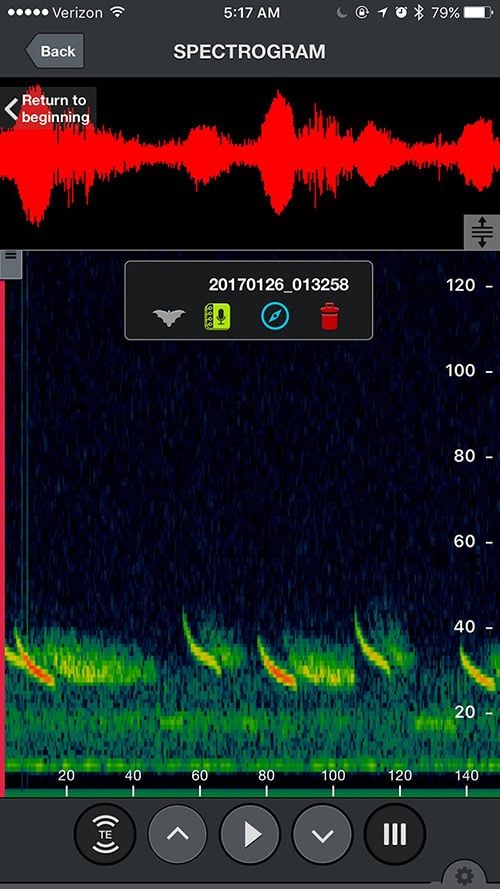

Many of these burgeoning bat walks feature something called the Echo Meter Touch, made by the company Wildlife Acoustics. This nifty bat-detecting gadget is the first acoustic bat identifier made for consumers, and comes in the form of an iPhone app with a microphone attachment. The microphone picks up silent bat calls, and the app visualizes them on a graph and converts them into a frequency that humans can hear. At the same time, it identifies what species of bat among the more than 50 bats that inhabit North America is making the call, and shows an illustration of that particular species.

The beauty of this interface is that it makes the invisible, visible—think of it as a wildlife metal detector, Shazam for bats, or a real-life Pokedex. “You don’t really get to see them because they’re flying around at night, but with an Echo Meter Touch, you really get a feel for how many bats are flying over your neighborhood park or your state park,” says Frick.

Frick has been using the Echo Meter Touch 2 Pro in her research in places as far flung as Fiji and Rwanda. Many of the bats she encounters aren’t yet entered into the program, so she records their calls and makes note of new species to begin building a bat call library. But for the public, she mainly sees this as a tool for education and outreach. She’s hoping that, at $179, the Echo Meter Touch 2 can be a “gateway drug” into lifelong bat appreciation. “People don’t realize how many bats are flying around in the night sky,” she says. “It could be a great tool to get more people aware and give them the opportunity to really interact with the bats that are there.”

Acoustic bat detectors have been around for decades, but there’s a reason they haven’t taken off. Unlike birds, bats don’t use their calls to claim territory or announce themselves to potential mates. Instead, the purpose of bat calls is to seek and destroy insects. That has two important consequences, as far as bat researchers are concerned. First, bats change their call frequency depending on the environment they’re in, meaning one bat can deploy many different calls. Second, different species of bats may share certain calls, because that frequency is particularly good at locating insects, meaning one call could indicate several species of bats.

These challenges have meant that, until now, bat detector use among hobbyists has been limited. Most of the ones used for bat walks in the UK are a simple version known as a heterodyne detector, which has to be tuned to a particular frequency and can only detect a single kind of bat at a time, says Frick. But over the past decade, improvements in mathematical algorithms have helped researchers disentangle the minute differences between different species’ ultrasonic calls.

Recently, Rohrbaugh and the Urban Bat Project put the Echo Meter Touch to use during one of D.C.’s first official bat walks. The event drew myself and around 40 other Washingtonians to Kingman Island, a thin sliver of land in the Anacostia River ringed with forest. On a warm August night, we watched the sky turn violet, and waited. Every now and then, what looked like a living pair of leaves would emerge from the silhouettes of trees that made up the darkening horizon. We’d squint to make out what it was: If it soared, it was a bird. If it flapped, it was a bat. Sometimes, it was just a very large mosquito.

Peering at the app on Rohrbaugh’s phone screen, we watched as previously unseen silver-haired bats, tricolored bats and hoary bats materialized onscreen. Later, her team caught a big brown bat in a mesh net—a smallish female who had recently given birth, with scarring on her wings from a past bout of white nose. She chirped audibly as Rohrbaugh untangled and examined her, her delicately translucent wings backlit by a flashlight. With her tiny pug face and almost imperceptibly small teeth, she was hardly the nocturnal nightmare that Hollywood might have prepared you for.

Compared to the other citizen science programs Rohrbaugh has organized, she was surprised by the instant popularity of a bat-themed event. She advertised the walk just a week prior on Facebook, and was immediately bombarded with more than 50 RSVPs for each of the two consecutive nights. There were “overwhelmingly quite a few people,” she says—which she hopes points to the potential for these kinds of programs to get the public invested in our nocturnal neighbors.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t mean the bat PR war is over yet. Unsavory myths persist, particularly the one about rabies (in fact, in many places, less than 1 percent of bats have rabies; of the 23 human rabies cases reported in the past 9 years, 11 were associated with bats). Bevan says that much of her organization’s work is turning around the negative PR campaign bats have faced, e.g. by helping citizens put up bat houses and plant bat-friendly native plant species. “There are definitely a lot of negative stigmas around bats, and we are always fighting that,” she says.

Yet for those who love them, these creatures have clearly transcended their darker associations. Frick recalls her first one-on-one bat experience with a yellow-winged African bat (Lavia frons) she encountered in the summer of 2000 as a field assistant in Kenya. She was a birder at the time, and came across the creature hanging from a tree while on the lookout for avians. “It was unlike anything I had ever seen before,” she says. "It's just a spectacular animal." She fell in love with bats that summer, she says—but also with the wildlife biologist she was working with, who is now her husband.

Frick instructs me to Google the bat, and I do. With its lush gray fur, upturned nose and cartoonishly large golden ears, it's a creature of undeniable alien glory. “See how freaking cool it is? Isn’t it just totally bizarre looking?” she says. “They’re so wild.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HeadshotGross_Web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HeadshotGross_Web.jpg)