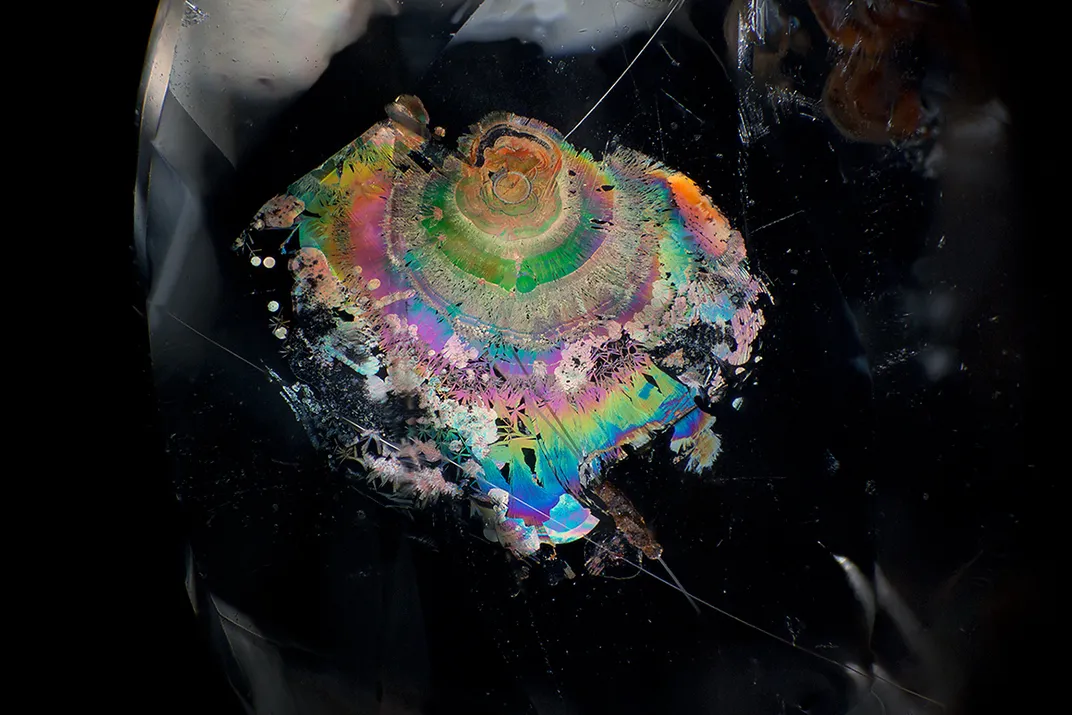

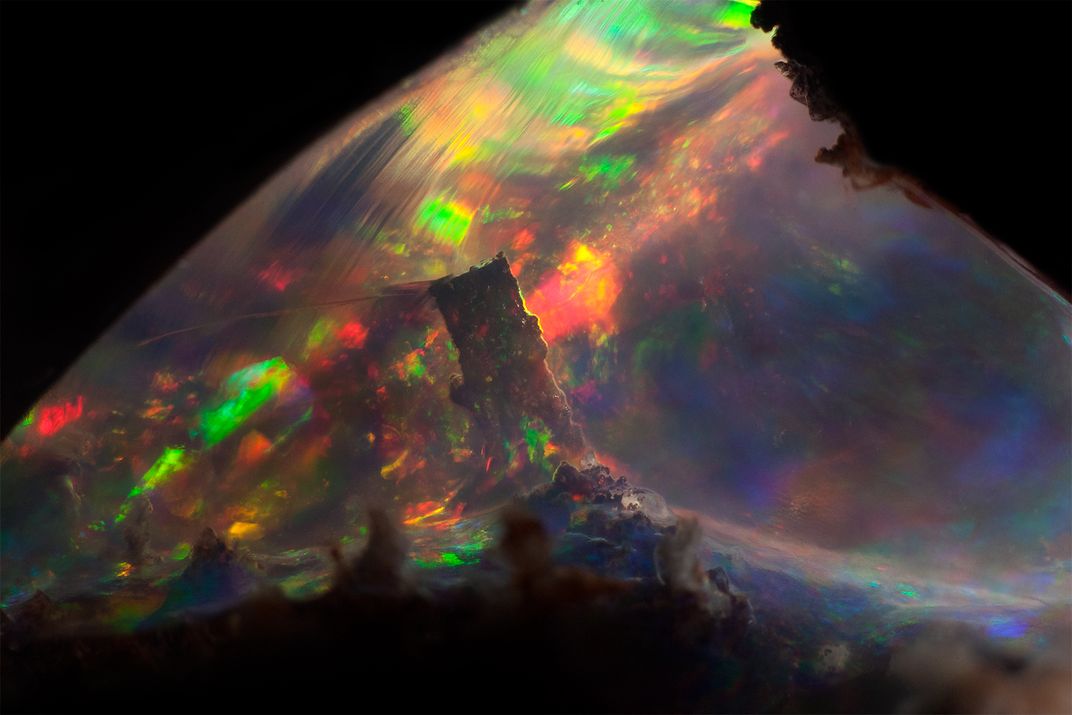

Surreal Photos Reveal the Otherworldly Insides of Gemstones

If you thought gems were beautiful to the naked eye, take a look at them under a microscope

Alice found her alternate universe down a rabbit hole; Galileo, through a telescope. Photographer Danny Sanchez finds his in gems under microscope.

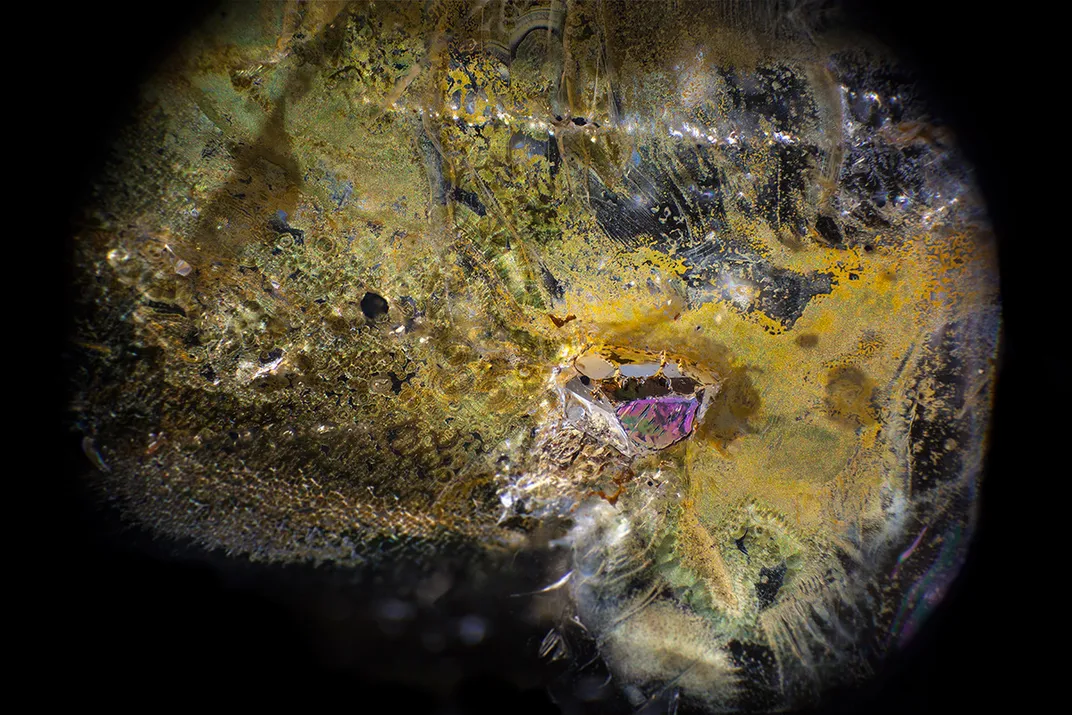

To collectors and sellers, an ideal gem is devoid of excess minerals called inclusions, which are seen as detractors of value or beauty. To many gemologists, inclusions are tools that can help them determine where a gem is from or under what conditions it formed.

But to Sanchez, a Los Angeles-based gemologist and photographer, inclusions are his portals into alien worlds. Back in 2005 Sanchez was working for the Distance Education Department of the Gemological Institute of America, ensuring that stones sent to students met the correct criteria. Looking at these stones under a microscope rendered them “wholly other” he explains, and he began to think, “I want to look at this forever.”

Inspired by the work of John I. Koivula and Eduard Gübelin in Photoatlas of Inclusions in Gemstones, Sanchez began teaching himself photomicrography, or the art of photographing under a microscope. Slowly but surely, he purchased tools from Craiglist and eBay to capture the inner worlds of gemstones and began to experiment.

Jeff Post has seen countless photos of gemstone inclusions in his work as curator of the Smithsonian's National Gem and Mineral Collection. “In the gem world … this is a very typical thing,” he says. “There are some famous gemologists … known for being able to study and identify inclusions in gems.” But no matter how many photos of inclusions he’s seen, Post says that the joy of viewing them doesn’t diminish. "Even though you've seen a hundred paintings at the National Gallery, if you go to another room, that doesn't mean you don't enjoy the next one just as much."

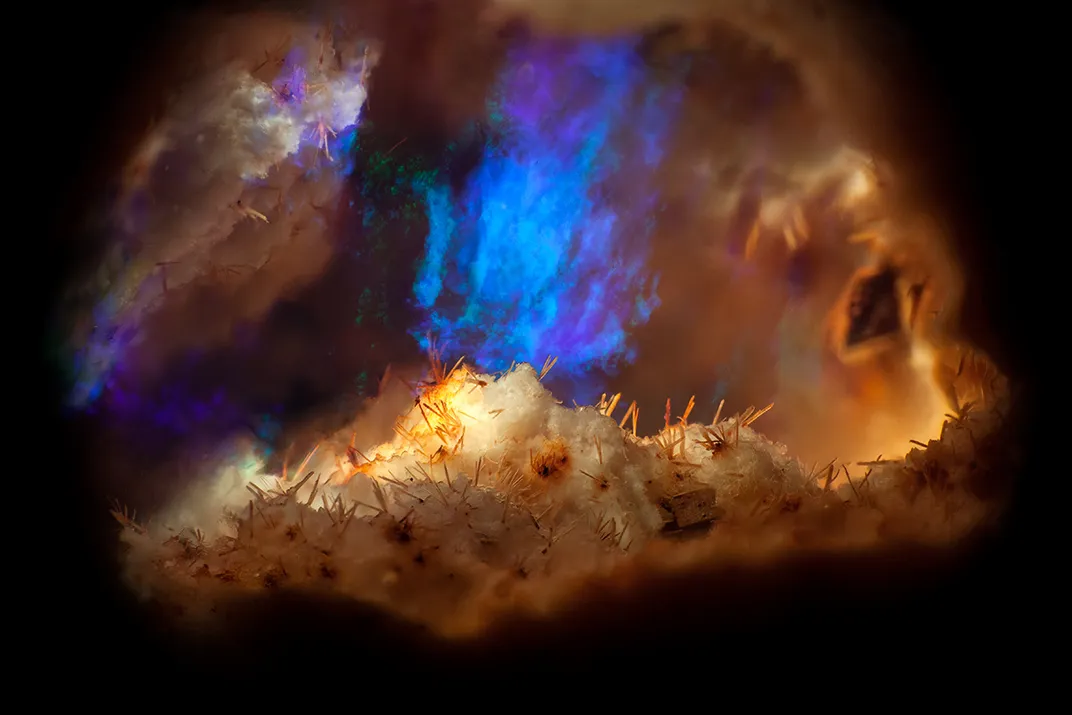

Where Sanchez says he differs from other photographers of gemstone inclusions is in his aesthetic. “I definitely don’t do it with an eye towards research or documentation," he explained. "I do it to stimulate the imagination." For instance, his photo of ferrous staining in quartz may remind viewers of mountains on Mars, and an image of titanium-based rutile in quartz brings to mind caves from Henry Levin's 1959 film Journey to the Center of the Earth. That’s the fun of his photography, he says: “People see what they want to see.”

Sanchez estimates that only one in ten stones that he purchases yields an interesting image. While he is able to gauge gems’ potential at trade shows with a magnifier, he can’t know for sure what he’ll see until he has them under the microscope.

Back in his studio, Sanchez directs light through fiber optics into a polished gem using thin silicon pipes, turning the stone over with his hand until he finds something that strikes him. Just finding that angle could take between 30 and 45 minutes. “If it doesn’t happen for me, I’ll put it down,” he says. “I’ll just put it away, and I'll look at something else. Every stone, and every photo, I have to feel excited about it.”

One of the challenges of shooting through a microscope is that there is no depth of field—the photographer's term for the varying levels of sharpness in an image that give viewers a sense of what's near and far. To compensate, Sanchez takes multiple photos at different points of focus. With a digital camera hardwired to his microscope and the stone and lights fixed in place by friction arms, he employs a vertical focus rail to make movements as small as 0.25 millimeters. He’ll take between 20 and 60 images to get through just one millimeter of depth, then he combines them in a process known as focus stacking to generate a final image.

Sanchez says he enjoys making gemstone inclusions “clear and illustrative” for an audience who has rarely, if ever, seen this kind of thing before. He recently showed his work at Art Basel in Miami, and he will shift more into the public eye with shows in Los Angeles, Mexico City and Brussels this year.

For more of Sanchez’s photos and information on his upcoming exhibits, visit his site here.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2018-08-01_at_7.20.11_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2018-08-01_at_7.20.11_PM.png)