Homer, Mary Shelley and Stephen King dreamed up horrific monsters that plague our nightmares. But the creatures in their stories can’t hold a candle to the gory, grotesque and vicious monsters that haunt the real world. From lizards that blast blood from their eyeballs to ants that decorate their nests with the skulls of their rivals, creatures with terrifying and fascinating adaptations have evolved to survive and flourish on our hostile planet.

Just in time for Halloween, Smithsonian magazine has rounded up 14 frightening facts about animals that out-spook even the scariest made-up monsters.

Decorating With Decapitated Heads

Serial killer Ed Gein, who made furniture and clothing out of human skin, inspired many classic horror films, including Psycho (1960), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and The Silence of the Lambs (1991). In a similarly demented fashion, a Florida ant species, Formica archboldi, decorates its home with the severed limbs and decapitated heads of its prey.

The ants usually go for easy targets, and they rarely pursue other ant species—with one violent exception. The most common “skull” found in F. archboldi nests belong to its beastly cousin Odontomachus, the trap jaw ant. A Predator-like predator, Odontomachus is capable of delivering 41 strikes per second with its rapid-fire mandible and powerful stinger.

On paper, F. archboldi should steer clear of such a brute, but to take down its foe, F. archboldi spits paralysis-inducing formic acid at the trap-jaw ant. Then, the headhunting critters drag their Odontomachus back to their nest for dismemberment, casting their victim’s remains aside, like humans tossing bones away while eating fried chicken.

Eaten Alive

Plenty of people are scared of snakes, but only seven percent are actually dangerous to humans. Toads, however, have to be on alert for the serpents more often—especially in small-banded kukri territory. Small-banded kukri snakes, Oligodon fasciolatus, are named for their teeth, which resemble and function like the deep-slashing, swift machete—called a kukri blade—used by Gurkha soldiers in Nepal and India.

When O. fasciolatus attacks a toad, it will often devour the amphibian alive. First, the serpent inserts its curved fangs into its prey’s soft belly, whipping its head from side to side to widen the incision. Then, the kukri plunges its head into the cavity, ripping out—in no particular order—the toad’s lung, heart, liver and stomach. The process can occasionally last hours, depending on the organs the snake pulls out first. No other snake in the world is known to feed this way, and it seems that the snake developed this gory technique to avoid the toad’s poisonous glands on its neck and back.

Mother’s Vomited Guts for Lunch

Lots of mothers feel pressured to give their children the world. Usually nourishment, protection, love and attention are enough. But not for India’s Stegodyphus lineatus spider-moms. These matriarchs sacrifice their blood, guts and life for their offspring.

Leading up to the birth of her babies, the arachnid mom binges on insects until her belly fills up. Meanwhile, her internal organs begin to liquify. For two weeks after she gives birth, she slowly vomits out her entrail slurry to feed her children as she wastes away and her body shrivels up. When she finally dies, her babies feast on her carcass.

Expelled Organs

When backed into a corner, sea cucumbers basically undergo a self-exorcism. But instead of ejecting evil spirits from their body, the creatures puke their guts out as a defense mechanism. Certainly expelling its organs would cause a sea cuke to meet its maker, right? Wrong! The spineless echinoderms, which are related to starfish and sea urchins, simply grow their viscera back in a few short weeks. By learning more about the genes behind this unique adaptation, scientists hope to apply their findings to advancements in regenerative medicine.

A Paralyzing, Liquefying Venom

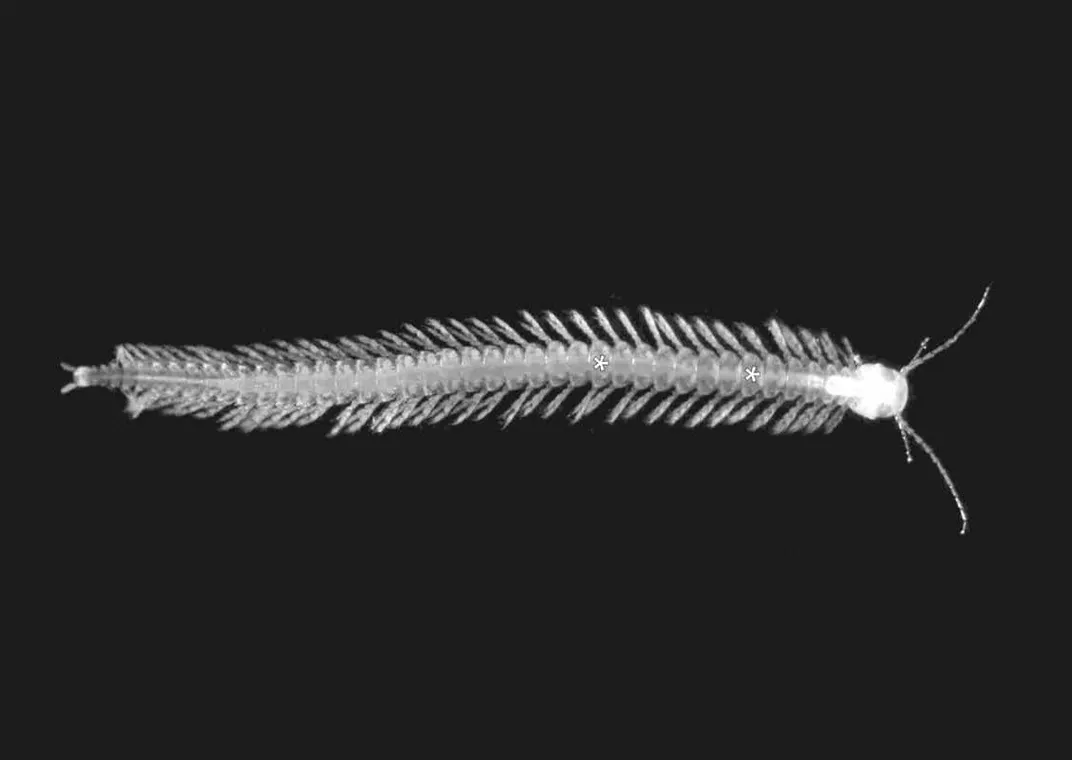

A blind, venomous crustacean called Xibalbanus tulumensis has a spider-like way of eating. The critter, which lives in underwater caves and looks like an inch-long centipede, sports tiny needle-like front claws that can inject neurotoxic venom. The creature squeezes venom, which includes a paralyzing agent and digestive enzymes, from reservoirs attached to its claws. Once the venom has liquefied the prey’s internal organs, the crustacean can slurp the slurry from their victim’s exoskeleton, like juice from a juice box.

Bite After Death

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/52/02/52023f77-fdc7-4891-b9ee-4015c44d428b/snake-751722_1920.jpg)

For most animals, decapitation means sudden death. But rattlesnakes don’t let dismemberment keep them down. Pieces of their body can still function over an hour after being sliced and diced. Though death is imminent, rattlesnakes can survive for at least an hour after being decapitated and can strike and inject venom into unsuspecting victims. Other chunks of the snake, including the signature rattle, can slither and shake hours after being dismembered.

A Diet of Blood

Vampire bats have sensitive nerves in their face act as heat sensors, guiding them to their next warm meal, be it a horse, cow or pig. They also have the sharpest teeth in the animal kingdom—which sink effortlessly into their victims and help them feed unnoticed. Special enzymes in their saliva prevent their blood-only diet from clotting as they slurp, and unique gut microbes help them digest blood and produce necessary proteins and vitamins. Only three bat species out of more than a thousand feed on blood, and they rarely bite humans.

Drinking From Festering Wounds

When riding atop rhinoceros, giraffes or zebras, oxpeckers look like adorable companions. The birds sound warning calls when danger approaches and eat parasitic critters—like ticks, flies and maggots—that live on their animal transporters. But these birds have a sinister side: they also feed on the blood of their host.

Oxpeckers, despite what their name suggests, don’t create wounds on their larger companions. Instead, they sip blood from festering lesions. Animals hosting oxpeckers tend to have more sores, and their wounds take longer to heal.

Bleeding a Gruesome Green

Green blood certainly sounds like something that would only run through the veins of an alien, as Star Wars’ Duros have. But five species of skink lizards native to New Guinea and the Soloman Islands have brilliant bright green liquid pumping through their circulatory system. Fittingly, these lizards belong to the genus Prasinohaema, which means green blood in Greek. And like the blue-green fleshed humanoids of planet Duro, these earthbound skinks are green through and through: They have green bones, muscles, tissues, tongues and mucous lining.

But it’s not easy being this green. The substance making these little reptiles viridescent is biliverdin, a pigment that triggers jaundice in humans. Green-blooded skinks have 20 times more biliverdin in their bodies than the highest level of the chemical ever found in a human—and for that person, the quantity was fatal.

The Sting That Kills

The humble box jellyfish, which has wandered the ocean for at least 500 million years, can kill a human in five minutes flat. Escaping its sight is nearly impossible: the creature has 24 eyes that give it a 360-degree view of its surroundings. Though it lacks a centralized organ for cognition, the predator has four primitive “brains” that make it hypersensitive to changes in its environment. The ghoul drifts through the abyss at a towering ten feet in length, with 15 tentacles, each covered in 5,000 stinging cells that deliver a fatal shock. Luckily, box jellies aren’t out to get you. They tend to reserve their stings for passing prey, like shrimp and fish, but when threatened, they will sting in self-defense.

Eating Their Mates

The bright red hourglass adorning a black widow’s body isn’t an ominous warning of impending death. It’s a signal to birds and other predators that they’re a not-so-tasty snack. In one study, scientists painted fake black widow spiders with and without the red hourglass. They found the all-black spiders were three times more likely to be snacked on by birds. Because dramatic coloration alerts the spider’s prey of danger, scientists think this hourglass shape is a balance between warding off predators and remaining stealthy to their own prey.

But black widows have earned a frightful reputation for the bright red hourglass on the abdomen for a reason; their neurotoxic venom is 15-times stronger than a rattlesnake’s. They use their fangs to inject venom into their prey, liquefying their meal. Black widows get their name from their grim mating behaviors, which often includes eating their mate after copulation.

Killer Skin Secretions

Golden poison dart frogs—the most toxic frog in the world—earn their name from the Emberá people of Colombia who use the frog’s secretions to coat the tips of their hunting arrows. The laced weapons can easily paralyze or kill an animal.

The frog’s bright colors ward of predators while giving them a hauntingly vibrant appearance, earning them the name, “jewels of the rainforest.” The frogs get their special powers from compounds in plants that their insect prey eats, which are then excreted through the frog’s porous skin. One frog secretes enough poison to kill ten men. But the golden poison dart frogs aren’t all doom and gloom—their toxins are cluing scientists into life-saving medical treatments like heart stimulants and pain killers.

Cute, But Deadly

The world’s only venomous primate is a slow-moving creature with a fluffy coat, adorably over-sized eyes and grooved teeth that can crunch through bone. Slow lorises derive their flesh-rotting venom from oozing glands in their armpits. When threatened, lorises clasp their tiny hands above their head and lick the gland’s toxic oily secretions which super-charge their bite. Their venom, which smells like rotting eggs, is volatile enough to decompose the flesh of others.

Slow lorises are one of just a handful of venomous mammals. Scientists think the primates evolved their toxic venom not to hunt prey, but to defend their territory from other lorises. A recent study found one in five slow lorises has a recent bite from a peer, and many had half-rotten ears, toes or faces. Their bite usually leads to anaphylactic shock in humans, but cases of loris bites are rare.

Birthed Out of Mother’s Back

People who feel physically ill at the sight of honeycomb-esque patterns of holes or cracks suffer from a condition called trypophobia. Because certain poisonous animals sport these circular clusters in the form of scales, for instance, some psychologists suggest the reaction triggered by this visual cue could be deeply rooted in our psyche, developed as an evolutionary survival response.

Regardless of how that specific fear came to be, the way Suriname toads give birth to dozens of babies at once that burst out of cavernous, clustered holes on their backs is sure to churn people’s stomachs—trypophobes or not.

When a female toad hears the call of a lover she fancies, she produces 60 to 100 eggs that bulge up under the skin of her back. The male caller fertilizes those eggs and the female takes cover for two to three months. When her babies are ready to hatch, the fully-formed toadlets rip through the thin layer of skin on her back, occasionally cannibalizing their siblings on the way.

The mother’s skin regenerates and she carries on until the next mating season, when she will repeat the brutal process all over again.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/fb/38fb3898-247b-4beb-87c8-e4f3a16c4379/gettyimages-569176479.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/corryn.png)