Forget Dinos: Horseshoe Crabs Are Stranger, More Ancient—And Still Alive Today

But now evolution’s ultimate survivors may be in danger

Each summer, guided by the light of the moon, some of the world’s strangest inhabitants ascend the East Coast’s beaches to spawn the next generation. These hard-shelled, many-eyed anomalies remind some of armored aliens or living spaceships. They're actually horseshoe crabs, and they date back 450 million years, having outlived the dinosaurs and survived five mass extinctions—including one that nearly wiped out life on Earth.

"They look like something you can imagine but never see," says wildlife photographer Camilla Cerea, who has begun documenting the charismatic crab and the people working to monitor it and save it from modern threats. "It's almost like seeing a unicorn."

Horseshoe crabs—in actuality, marine arthropods that aren’t even distantly related to crabs—aren’t just a curiosity to ogle on the shore. Their bluish, copper-tinged blood is used to test for toxic bacterial contamination, meaning you have them to thank if you’ve ever used contact lenses, had a flu shot or ingested medicinal drugs. Humans bleed 500,000 of the creatures a year to procure this medically valuable substance, before returning the crabs to the waters.

But now, the lethal combination of climate change, habitat loss and over-harvesting means that these living fossils face their biggest existential challenge yet.

Thanks to shoreline development and sea level rise worsened by climate change, horseshoe crabs are steadily losing the beach habitats they rely on for mating and breeding. In addition to extracting their blood, humans harvest the creatures to use as bait for fishing eels and whelk; in some parts of the world humans also eat their eggs or the animals themselves. Last year, the Atlantic horseshoe crab was listed as “vulnerable” on the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, with some populations facing even greater risks.

Cerea first heard about horseshoe crabs through her day job as a photographer for the National Audubon Society. The birds that the society is devoted to protecting often feed on their clutches of tasty blue eggs, and as the crabs have declined in some regions, so have birds. When Cerea first looked up the arthropods online, she was captivated. "Honestly, I had never seen something like that in my entire life," she says.

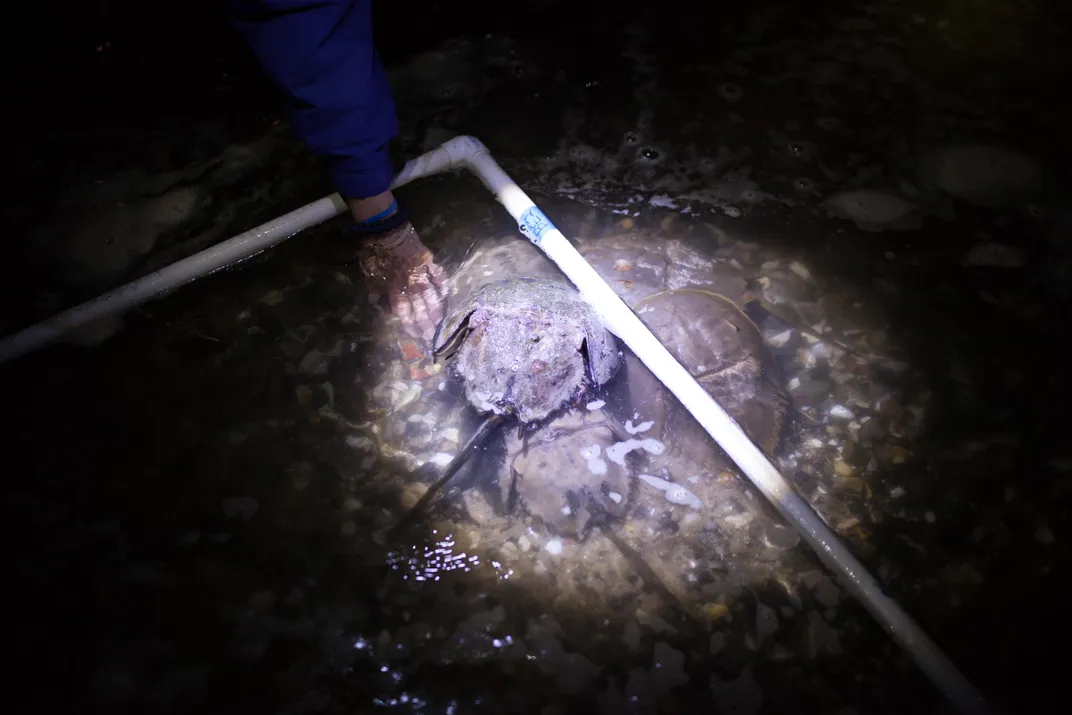

She soon found out she wasn't alone in her appreciation. During their summer breeding season, a devoted corps of volunteers organized by Cornell University and NYC Audubon patrols the beaches of New York City at night to count the horseshoe crabs, and tag them for tracking. "Every volunteer has a different reason to be there," Cerea says. "But everybody has an amazing passion about the horseshoe crabs themselves."

The monitoring in New York is done for this year, but Cerea plans to be back again next year—both as a photographer and a volunteer. "It's such an important and tangible animal, and very few people know it," Cerea says. "They're even older than dinosaurs, but they're real, they're there." Let’s hope we don't end up being the reason that evolution's ultimate survivors aren't here in another 450 million years.