Eek! Each of These Insect Portraits Is Made From More Than 8,000 Images

With a mastery of macro, Levon Biss captures every hair and dimple on insects’ vibrant bodies

These spectacular images have modest roots: a photographer's son finding bugs in the garden.

Levon Biss is known for his breathtaking portraits, from filmmaker Quentin Tarantino to Olympic track star Jessica Ennis-Hill. But his work keeps him traveling, so the London-based photographer was in search of a compact side project that he could dip in and out of during his short stints home.

His son's insect collection proved the perfect subject. “And it all went from there, really," says Biss. "I didn't have a big master plan to create this project, it was something that happened quite organically.”

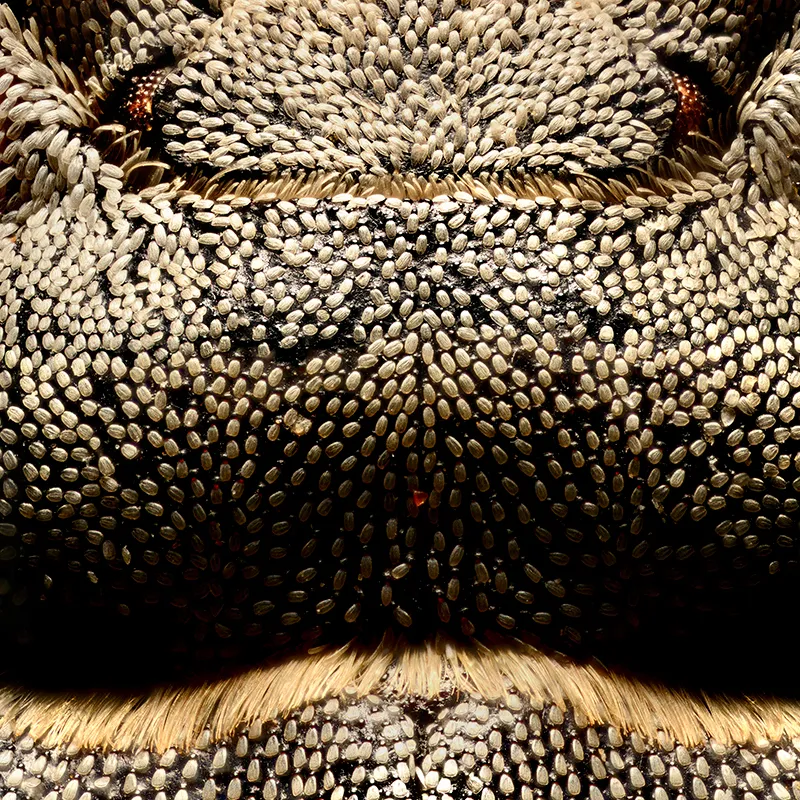

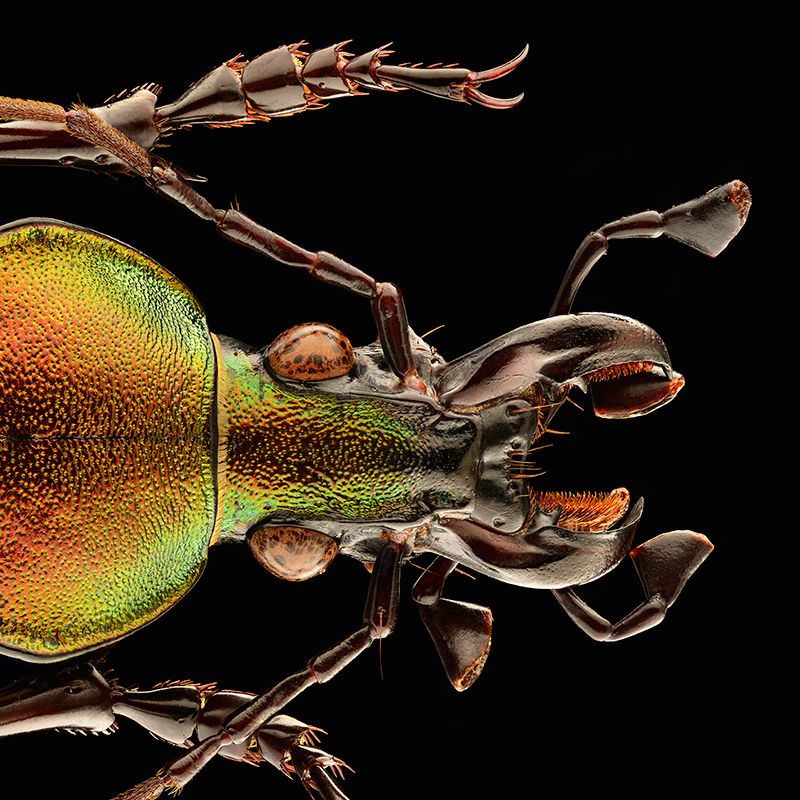

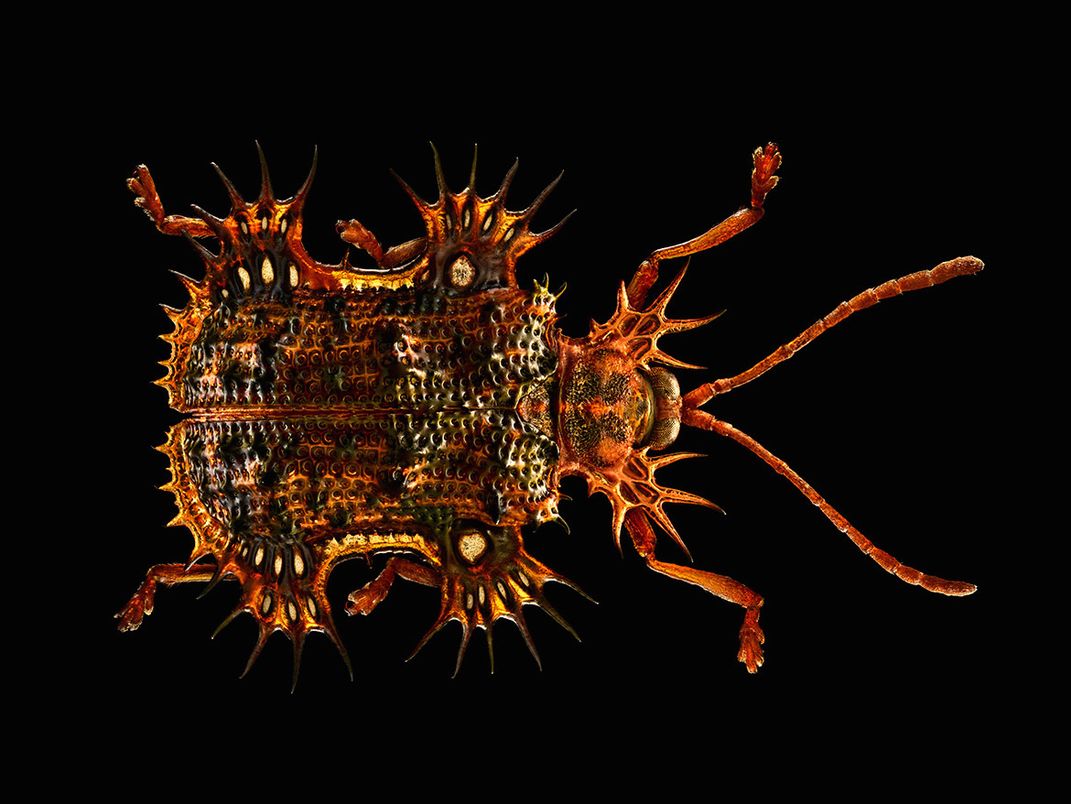

Attracted to the technical aspects of photography, the bug portraits allowed Biss to dabble in the challenging macro world, imaging the most minute details of his already tiny models. Using a microscope lens mounted to his camera, he developed a technique to capture every dimple on their vibrantly colored bodies.

Biss took several of his images to staff at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History in hopes of tapping into its collections of nearly seven million insect specimens.

“He was explaining what he was doing,” recalls James Hogan, an entomologist at the museum. “And then he just kept zooming in on the images.” As Hogan saw a ground beetle, baby bush cricket and a fly in progressively greater detail, he was floored. “Normally you zoom in on an image and it becomes pixelated quite quickly,” he says. But Biss’ images captured every hair on the bugs’ tiny legs.

Two years and countless hours of work later, Biss’ photographs were featured in “Microsculpture,” an eight-month exhibition that opened at the museum in May 2016. The collection included 24 large-scale prints paired with the actual specimens that Biss and Hogan carefully selected from the drawers where they are preserved behind the scenes.

Now, a selection of Biss' gorgeous large-format photographs are featured in a new book of the same title, Microsculpture, released this week.

The images highlight details in nature that are easy to overlook. “You would think perhaps that the surface of an insect would be really smooth,” Hogan says. “But when you’re really zoomed in, it’s not at all. There’s a whole layer of complexity there that’s not usually apparent.”

These minute curves, depressions and textures most likely have a purpose. The microscopic texture of shark skin, for example, reduces friction as they swim, helping them glide faster through the water. But determining the reason for these structures in the tiny world of bugs has largely eluded scientists, Hogan explains. By making these mysterious structures larger than life, Biss could perhaps inspire future entomologists to study them.

To capture these microsculptures, Biss attaches a microscope lense to the front of his camera, which allows him to magnify the bugs 10 times their normal size. But looking through such magnification strictly limits his depth of field. This means that only a small fraction of the image can be in focus at any given time.

Biss overcomes this problem by mounting the whole camera to a contraption that allows him to adjust its distance away from the bug, and his focal point, by 10 micron intervals. To put that into perspective, a hair on a human’s head is roughly 75 microns thick, Biss explains. So photographing a single hair would take about seven shots. Hundreds of images are required to create a single sharp image of each section of the bug.

Even so, this was only part of the process. Biss was determined to not lose his own artistic style while photographing his tiny subjects. “I like to sculpt my images with light,” he says. But applying this style to bugs, some of which are less than an inch tall, was a challenge. “You've got no real control over the light,” Biss explains, “the way it falls on the insect.”

Microsculpture: Portraits of Insects

Microsculpture is a unique photographic study of insects in mind-blowing magnification that celebrates the wonders of nature and science. Levon Biss’s photographs capture in breathtaking detail the beauty of the insect world and are printed in large-scale format to provide an unforgettable viewing experience.

To compensate for wash out, Biss divided every insect into roughly 30 sections, photographing and lighting each part separately. With all sections combined, each portrait is a composite of anywhere from 8,000 to 10,000 separate photographs.

Selecting the right creatures from the museum’s vast collection is key to Biss’ success. Biss looked for subjects that were visually appealing. But Hogan also wanted each insect to be scientifically interesting.

“We selected things that were a bit unusual, a bit weird, or perhaps things that people might not have seen before,” explains Hogan.

For example, Hogan’s favorite insect in the show was the marion flightless moth, Pringleophaga marioni, a bizarre-looking creature that can even befuddle practiced entomologists, he says. The sharp magnification of Biss’ image, however, gives away the bug’s identity since it reveals a layer of scales covering its body, a feature that is common to Lepidopteran.

The insects also have to be completely clean. At such a high magnification, the tiniest speck of dust becomes obvious.

That said, there’s one insect in the set that remains dirty: the tricolored jewel beetle. This 160-year-old bug was collected by A.R. Wallace—a contemporary of Charles Darwin.

“There's lots of dirt and grime on that one, but that dirt and grime is 160 years old,” says Biss. “It's historic[al] dirt and grime.”

The series invokes a sense of awe in both the spectacular beauty of nature and Biss’ command of macrophotography. With these images, Biss hopes to restore some respect to photography that he believes has been lost in the age of cell phone cameras and constant photo-documentation.

By spending nearly a month creating a single image of a creature, it becomes more than a snapshot, he explains. “That image to me has a gravitas. It has a weight to it. It has a sense of value.”

Editor's Note: This story, originally published on May 16, 2016, was updated on October 12, 2017 to reflect the publication of Levon Biss' Microsculpture, a new book of the photographer's detailed insect portraits.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)