Dust from the Sahara Can Seed Rain and Snow Clouds Over the Western U.S.

Clouds above California contain dust and bacteria from China, the Middle East and even Africa, new research shows

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Surprising-Science-Dust-631.jpg)

The fascinating idea that a butterfly flapping its wings in Asia can change the path of a hurricane over the Pacific is, alas, probably not accurate. But slight changes in one part of the atmosphere can indeed have disproportionate effects elsewhere, a concept known as the butterfly effect.

Just how slight one of these factors can be—and how incredibly far away their effects can reach—is vividly illustrated by a new finding by an international team of atmospheric scientists and chemists from the U.S. and Israel. As they document in a study published today in Science, dust blown from as far away as the Sahara desert of Africa can seed rain and snow clouds in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California.

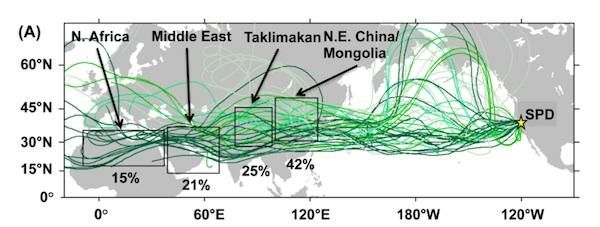

The research team, led by Kimberly Prather of the University of California, San Diego, came to the finding after using aircraft to collect atmospheric data over the Sierra Nevada mountains, as well as analyzing precipitation that fell at the Sugar Pine Dam in Northern California. They also retroactively tracked storm masses backward across the Pacific and Asia to pinpoint the origin of the dust they found in the clouds.

Cloud formation depends upon tiny particles such as dust that serve as cloud condensation nuclei or ice nuclei—flecks that act as a surface on which water can condense. Previous studies have found that dust from as far away as the Taklimakan desert in China can be blown around the globe. But temperate deserts such as the Taklimakan and the Gobi are frozen much of the year, while the Sahara never freezes, the researchers noted. Could the Sahara and deserts in the Middle East serve as a significant source of year-round dust which, when lofted high into the atmosphere, seeded storms across the planet?

The answer is yes. Of the six storms the researchers sampled, all showed at least some trace of dust. Then, working backward to determine the origin of each of these air masses and using existing data from previous studies on wind currents across the Pacific, they found strong evidence that the majority of the dust had originated in Africa, the Middle East or Asia and traveled around the globe. Additionally, the observed height of various drafts of dust (as collected by a U.S. Navy program) on the days when the air masses would have moved past the African and Asian regions matched the altitude necessary for the particles to get lifted up into the air currents.

Satellite analysis of the storm masses as they moved across the Pacific also confirmed that they carried dust all the way. As shown in the map above, most came from Northeast China or the Taklimakan, but a sizable amount came from as far as the Middle East or even the Sahara.

Although the butterfly’s role in all this seems to be nonexistent, the study did find that one type of living creature does play a part in cloud formation: bacteria. In recent years, scientists have discovered that bacteria, along with dust, can be lofted up high in the atmosphere and serve as nuclei for cloud formation. In this study, the researchers found that small amounts of bacteria were mixed in with the dust, and likely originated in Asia and Africa as well.

So if you live on the West Coast, the next time you get caught in a rainstorm think of this: Each drop that hits you might contain dust and bacteria that’s traveled halfway around the planet. A close look at something as mundane as our daily weather, it turns out, can open a new window to the complex interconnectedness of our world.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)