The Dubious Science of Genetics-Based Dating

Is love really just a cheek swab away?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11/f2/11f2daed-6cf6-47b2-a867-8282f5ae5c5a/dsc06463.jpg)

We live in a golden age of online dating, where complex algorithms and innovative apps promise to pinpoint your perfect romantic match in no time. And yet, dating remains as tedious and painful as ever. A seemingly unlimited supply of swipes and likes has resulted not in effortless pairings, but in chronic dating-app fatigue. Nor does online dating seem to be shortening the time we spend looking for mates; Tinder reports that its users spend up to 90 minutes swiping per day.

But what if there was a way to analyze your DNA and match you to your ideal genetic partner—allowing you to cut the line of endless left-swipes and awkward first dates? That’s the promise of Pheramor, a Houston-based startup founded by three scientists that aims to disrupt dating by using your biology. The app, which launches later this month, gives users a simple DNA test in order to match them to genetically compatible mates.

The concept comes at a time when the personalized genetics business is booming. “Companies such as 23andMe and Ancestry.com have really primed the market for personalized genetics,” says Asma Mizra, CEO and co-founder of Pheramor. “It's just becoming something that people are more familiar with.”

Here’s how it works: For $15.99, Pheramor sends users a kit to swab their saliva, which they then send back for sequencing. Pheramor analyzes the spit to identify 11 genes that relate to the immune system. The company then matches you with people who are suitably genetically diverse. The assumption is that people prefer to date those whose DNA is different enough from their own that a coupling would result in a more diverse, likely-to-survive offspring. (The way we can sense that DNA diversity is through scent.)

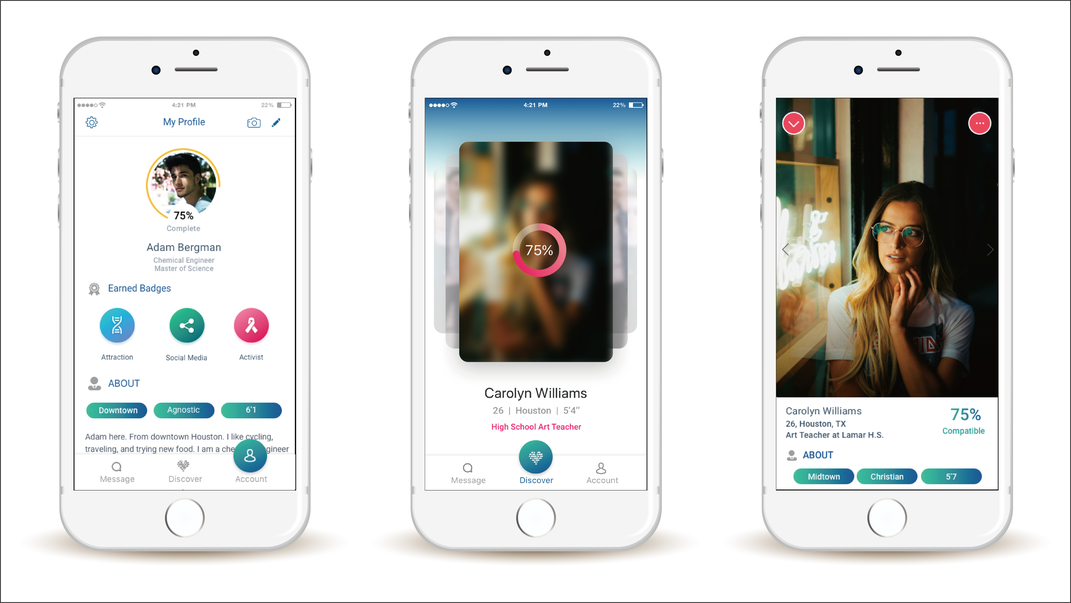

Pheramor does not just look at genetic diversity, though. Like some dating apps, it also pulls metadata from your social media footprint to identify common interests. As you swipe through the app, each dating card will include percent matches for compatibility based on an algorithm that takes into account both genetic differences and shared common interests. To encourage their users to consider percentages above selfies, prospective matches’ photographs remain blurred until you click into their profiles.

“I've always been motivated to bring personalized genetics to everyday people,” says Brittany Barreto, Chief Security Officer and co-founder of Pheramor. “We don't want to be gatekeepers of the scientific community. We want people to be able to engage in science, everyday people. And realize that it is something that you can use to make more informed decisions and have that agency to make those decisions. So we're saying, you're not going to find your soulmate but you're probably going to go on a better first date.”

But can the science of attraction really solve your dating woes?

The Genetics of Love

Pheramor claims to “use your attraction genes to determine who you are attracted to and who is attracted to you.” That's not entirely true; there are no "attraction genes." (Or if there are, we haven't found them yet.) What Pheramor is actually comparing are 11 genes of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which code for proteins on the surface of cells that help the immune system recognize invaders.

The idea of linking immune system genes to attraction stems from a 1976 study published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, in which scientists found that male mice tended to select female mice with dissimilar MHC genes. The mice detected those genes through scent. Researchers hypothesized reasons for this selection ranging from the prevention of inbreeding to promoting offspring with greater diversity of dominant and recessive genes. In 1995, a Swiss study applied the concept to humans for the first time through the famous "sweaty T-shirt study." The research showed that, like the mice, the women who sniffed the sweaty garments were more likely to select the shirts of men with greater genetic difference.

But experts caution the science behind matching you with someone who has different immune system genes remains theoretical. One is Tristram D. Wyatt, a researcher at Oxford who authored a 2015 paper on the search for human pheromones published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society. As an example, Wyatt cites the International HapMap Project, which mapped patterns in genetic sequence variants from people from all around the world and recorded their marital data.

“You might expect that if this was a really strong effect, that people really were choosing their partners on the basis of genetic difference of the immune system genes, that you would get that ... out of the data," he says. “And it didn’t work out that way. One research group found, yes, people were more different than you’d expect by chance. And another research group using the same data but slightly different assumptions and statistics said the opposite. In other words: there was no effect."

Pheramor isn’t the first dating app to look to genetics for dating. Back in 2008, GenePartner launched with the tagline “Love is no coincidence,” and also calculated partner preference based on two people's diversity of MHC genes. In 2014, Instant Chemistry entered the market with a tailored concept to show people already in relationships how “compatible” they were based on their MHC diversity. That same year, SingldOut (which now redirects to DNA Romance) promised to use both DNA testing and social networking information from LinkedIn.

Unfortunately, the science behind these all companies’ claims stems from that same mouse research done back in the 1970s. “It’s a lovely idea,” says Wyatt, “but whether it actually is what people or for that matter other animals are doing when they choose a mate is up in the air.” In other words: No, you still can’t reduce love to genetics.

The Problem with Human Pheromones

On its website, Pheramor claims that these 11 “attraction” genes create pheromones, or chemical signals, that make you more or less attractive to a potential mate. The site’s science section explains “science of pheromones has been around for decades” and that they “are proven to play a role in attraction all the way from insects to animals to humans.” It continues: “if pheromones tickle our brain just the right way, we call that love at first sight.”

None of this is true. “Pheromone is a sexy word and has been since it was invented,” says Wyatt. But the science of pheromones—specifically human pheromones—is still cloudy at best.

First identified in 1959, pheromones are invisible chemical signals that trigger certain behaviors, and are used for communication in animals from moths to mice to rabbits. Since then, companies have claimed to use pheromones in everything from soap to perfume to help humans attract a mate. (Fun fact: If you’ve used a product that claims to use pheromones, most likely it was pig pheromones; pig sweat shares chemicals in common with human sweat but we have no idea if they have any effect on us, reports Scientific American.) In 2010, headlines began reporting on Brooklyn’s “Pheromone Parties,” a trend that seized on this idea by having people sniff each other’s t-shirts to supposedly detect genetic diversity.

In fact, we’ve never found pheromones in humans. Scientists are still searching for the fabled “sex pheromone,” but so far they’re nowhere close. In their defense, there are several challenges: For one, you have to isolate the right chemical compound. For another, there’s the chicken-and-the-egg problem: if a chemical does create a behavioral response, is that an innate response, or is it something learned over time through culture?

Pheramor points to that famous “sweaty T-shirt study,” as supporting evidence for pheromones. However, later attempts to isolate and test alleged pheromones—such as steroids in male sweat and semen or in female urine—have failed. And in 2015, a review on the scientific literature on pheromones found that most research on the topic was subject to major design flaws.

Right now, Wyatt thinks our best bet for hunting down the first human pheromone is in maternal milk. Infants seem to use scent to find and latch on to their mother’s nipples, and some researchers believe a pheromone could be responsible. Looking at babies rather than adults has the added benefit of getting rid of the acculturation problem, since newborns haven’t yet been shaped by culture.

But until we find it, the idea of a human pheromone remains wishful hypothesizing.

.....

In short, whether it’s worth it to swab for love is something that the scientific community is not ready yet to assert. “You’d need a lot more research, much more than you have at the moment,” says Wyatt. However, Pheramor could actually help expand that research—by increasing the data available for future research on MHC-associated partner choice.

The team has established a partnership with the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University, a leader in studying human attraction and sexuality, which plans to hire a dedicated post doc to look at the data Pheramor collects and publish papers on attraction. Justin Garcia, a research scientist at the Kinsey Institute, says that the data Pheramor is amassing (both biological and self-reported) will offer new insight into how shared interests and genetics intersect. “That is a pretty ambitious research question but one I think they in collaboration with scientists here and elsewhere are positioned to answer,” he says.

One area they want to expand on is the research on genetic-based matching in non-heterosexual couples. So far, research on MHC-associated partner choice has only been done in couples of opposite sexes—but Pheramor is open to all sexual preferences, meaning that researchers can collect new data. “We let [users] know, right from the get go that the research has been done in heterosexual couples. So the percentage that you see may not be completely accurate,” Mizra says. “But your activity on this platform will help us to publish research papers on what the attraction profiles in people who identify as LGBTQ are.”

Beyond adding data to the research, Pheramor could also help address the lack of diversity on dating apps. Statistically speaking, Mizra points out, women of color are the most “swiped left on” and “passed” in dating apps. As a Pakistani-American who is also Muslim, she knows personally how frustrating that kind of discrimination can be.

“So how do we change that perspective if we truly believe that we're bringing a more authentic and genuine connection?” she says. “One of the things that we're doing is we're saying, ‘You know what? Let the genetics and let the data kind of speak for itself.’ So, if you have a 98 percent compatibility with someone that you probably wouldn't think you'd get along with, why don't you give it a try?”

For now, the team is focused on getting their app, currently in beta testing, ready for roll out. They’re hoping to launch with 3,000 members in Houston, after which they want to expand to other U.S. cities. “Our app is really novel, it's really new and I don't think it's for everybody,” says Barreto. “It's for people who understand which direction the future is heading and which direction technology is heading and how quickly it moves. And I think over time people will become more comfortable with it and realize the value in that.”

In the end, swabbing your DNA probably won’t get you any closer to love. On the other hand, none of those other fancy dating algorithms will, either. So swab away: what do you have to lose?