Dinosaur Diamond: Utah Field House of Natural History

The humor and use of specimens to highlight fossil mysteries make this dinosaur museum an essential stop

![]() There are dinosaurs everywhere in Vernal, Utah. A old-school sauropod advertises for a Best Western hotel, a pair of tussling Allosaurus skeletons adorns the side of a downtown building, and a bikini-clad version of Vernal’s dinosaur mascot, Dinah, invites visitors for a swim on a fading sign along the town’s main drag. But if you want a look at real dinosaurs—or at least the casts of real dinosaur skeletons reassembled into their natural forms—you have to stop by the Utah Field House of Natural History.

There are dinosaurs everywhere in Vernal, Utah. A old-school sauropod advertises for a Best Western hotel, a pair of tussling Allosaurus skeletons adorns the side of a downtown building, and a bikini-clad version of Vernal’s dinosaur mascot, Dinah, invites visitors for a swim on a fading sign along the town’s main drag. But if you want a look at real dinosaurs—or at least the casts of real dinosaur skeletons reassembled into their natural forms—you have to stop by the Utah Field House of Natural History.

If you come at the museum from the east along Main Street, you can’t miss it—a huge, green Tyrannosaurus yawns from behind a wall which encloses a trail of classic dinosaur sculptures. These aren’t the lithe, agile animals of Walking With Dinosaurs or even modern museum displays like those inside the museum itself, but bulky creatures which represent an outdated—but not forgotten—image of prehistoric life. These are your father’s dinosaurs.

The interior of the museum is a different story. Casts of Allosaurus and Diplodocus skeletons greet visitors in the spacious foyer, and a nearby alcove displays reproductions of some of the most impressive skeletons discovered at Dinosaur National Monument (itself a 20 minute drive east, straight out of town). There’s a cast of the beautiful, articulated skeleton of the juvenile Camarasaurus which is on display at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, but the real gem is a reproduction of the slightly jumbled skeleton of Allosaurus jimmadseni. The specimen represents a second species of Allosaurus (currently on its way to scientific publication) and honors the late James Madsen, Utah’s first state paleontologist and the author of the impressive monograph Allosaurus fragilis: A Revised Osteology. (I was actually surprised to find a hard copy of Madsen’s study for sale in the gift shop for a paltry $11—a find that made this paleo-nerd very happy, indeed.)

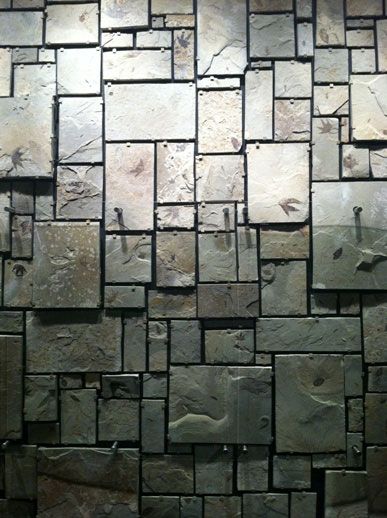

From the expansive foyer, visitors to the museum can walk through a winding corridor that leads through several glimpses of prehistory in eastern Utah. Though I was there for the dinosaurs, I have to say that the exhibit on the fossils of the approximately 45-million-year-old Green River Formation was especially impressive, including a gorgeous collage of well-preserved plant fossils making up one of the exhibit’s walls. Given the proximity of the museum to Dinosaur National Monument, though, the stars of the museum are the dinosaurs in the Jurassic exhibit.

Inside the dim interior of the dinosaur hall, a Stegosaurus and Allosaurus strike poses in front of a beautiful mural of life during the days of the Morrison Formation, while a prostrate and decapitated skeleton of the sauropod Haplocanthosaurus helps demonstrate the enduring nature of fossil mysteries. Since paleontologists don’t know what the head of Haplocanthosaurus looked like, the exhibit explains, the head of the dinosaur restored in the mural is only a temporary sketch taped onto the painting until a skull is found. This kind of humor and use of specimens to highlight fossil mysteries make the Utah Field House of Natural History stand out from the many other dinosaur museums in the region, and make the institution an essential stop for anyone traveling the northeastern part of the Dinosaur Diamond.

To see more from the Utah Field House of Natural History, check out the gallery below.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)