Digging for the Secrets Beneath Antarctica

Scientists have found life in the depths beneath the ice

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/What-Lies-Beneath-WISSARD-camp-631.jpg)

In early January, the start of summer in Antarctica, a dozen tractors towing sleds laden with 1.2 million pounds of scientific equipment completed a two-week trek from the United States’ McMurdo Station to a site 614 miles across the ice. More than 20 researchers who had arrived by plane used the gear to bore a hole nearly half a mile into the ice—becoming the first people ever to fetch a clean sample from one of the continent’s hidden lakes, arguably the most pristine bodies of water on the planet . What they found promises to open a new chapter in our understanding of life on earth.

For several decades at least, scientists have known that vast chambers filled with water lie untouched beneath Antarctica’s 5.4-million- square-mile ice sheet. With remote sensing tools, they have mapped nearly 300 subglacial lakes, kept from freezing by geothermal warmth. Any organisms living there, scientists think, might be unlike earth’s other residents, having been locked away for up to millions of years.

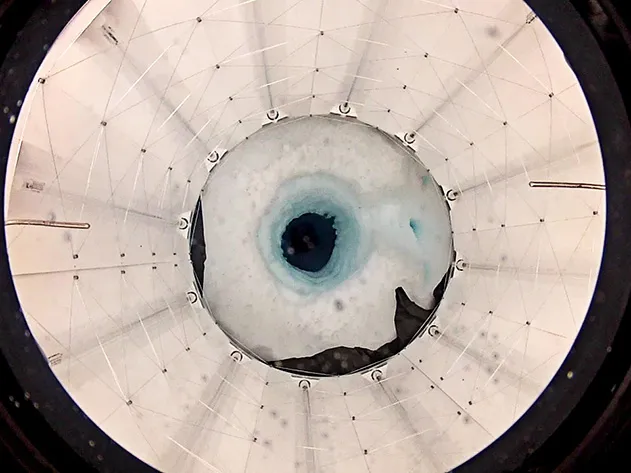

Members of the U.S.–led Whillans Ice Stream Subglacial Access Research Drilling (WISSARD) project targeted a lake at the southeastern edge of the Ross Ice Shelf. More than 2,000 feet beneath the surface, Lake Whillans covers around 20 square miles. Over three days, the researchers used hot water to drill a 20-inch-wide hole down to the lake before sending a robotic submarine in for pictures and videos. The team then spent four days—working around the clock in the brutal cold—pulling up water and sediment from the lake’s bottom. Avoiding contamination was a major concern: The hot water flowing into the bore hole at 30 gallons per minute was filtered and, to kill remaining microbes, pulsed with ultraviolet light. The remote sub, cameras and cables were also sterilized.

In laboratories set up in shipping containers, scientists right away found signs of life in the lake—the first evidence of its kind. Cells were visible under a microscope. And tests showed evidence of ATP, a phosphorus-containing compound that helps regulate energy in living cells. The findings suggest a “huge sub-ice aquatic ecosystem” swimming with microbes, says John C. Priscu, an ecologist at Montana State University and WISSARD chief scientist. “We’re giving the world the first glimpse of what its like under this huge Antarctic ice sheet that was previously thought to be dead.”

Other scientists had tried to delve into Antarctica’s hidden realm. In December, a British team called off an effort to reach Lake Ellsworth because of technical difficulties. And a Russian project aimed at Lake Vostok retrieved samples bathed in kerosene from the drilling process .

Back in climate-controlled labs in the States and Europe, Priscu and his colleagues have been running more tests. Any day now, they expect to publish results describing what exactly lives in Lake Whillans and how it survives there.

What’s next for the scientists depends on what the tests reveal, says University of Edinburgh geoscientist Martin Siegert, who led the drilling attempt at Lake Ellsworth. In the next decade, Siegert expects, scientists will find “several hundred more” of these watery Antarctic reservoirs. But he doubts this pure exploration of our planet will last much longer: “We’re in the last phase of pursuing information where nobody has set foot.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)