Biologists Pinpoint Bacteria That Increase Digestive Intake of Fat

A new study in zebrafish found that certain types of gut bacteria lead to a greater absorption of fat during digestion

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120913085046Staphylococcus_aureus_bacteria_escape-small.jpg)

You may have read this remarkable fact several times over, but it bears repeating: There are at least ten times as many bacteria cells as human cells in your body. And in contrast to conventional wisdom, not all these bacteria do you harm—in recent years, a number of experiments have shed light on the profoundly important role bacteria play in the healthy functioning of our bodies. The human microbiome (which refers to the trillions of microorganisms that live on your skin, in your saliva and inside your digestive tract) has been found to help our bodies digest complex carbohydrates, kill dangerous pathogens and even assist in directing the development of cells and organs.

Now, for the first time, a team of biologists has identified a type of bacteria that resides in the digestive tract and increases the intake of fat into the intestine. According to a study published yesterday in Cell Host and Microbe, researchers from the University of North Carolina and elsewhere have directly observed that bacteria from the phylum Firmicutes play a key role in promoting the absorption of fat from food. Although the observations took place in zebrafish, previous studies have found a correlation between the abundance of bacteria from this same phylum and obesity in humans.

“This study is the first to demonstrate that microbes can promote the absorption of dietary fats in the intestine and their subsequent metabolism in the body,” said John Rawls, one of the study’s authors. “The results underscore the complex relationship between microbes, diet and host physiology.”

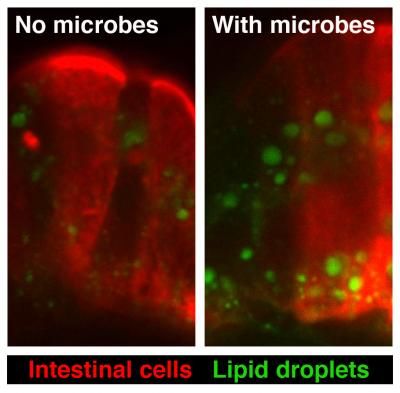

To observe the role of the microbes in fat digestion, the research used zebrafish, because the fish are nearly transparent when young. By using two groups of fish—one that had normal populations of gut microbes and one that was raised “germ-free,” in a sterile environment—and feeding them specially formulated fatty acid molecules that had been tagged with a florescent dye, they could see if the microbes affected fat absorption.

The answer was clear: The presence of the Firmicutes populations led to much higher amounts of fat absorbed from the very same foods, meaning a higher caloric intake from the same diet. Here’s a side-by-side comparison of cells that line the zebrafish intestines, with lipid droplets in green due to the florescent dye:

Most intriguingly, the researchers found that the Firmicutes bacteria didn’t just play an active role in helping the zebrafish absorb fat—the population of the bacteria itself was influenced by diet, as fish fed normally had higher abundances in their digestive tracts than fish denied food for several days. In previous studies, mice that gained weight due to a fattier diet developed larger populations of Firmicutes than mice on a normal diet, and when researchers transferred bacteria samples from the obese mouse’s intestines to those of the normal mice, the latter group absorbed more fat from the same diet as before.

This indicates that the relationship between Firmicutes bacteria and fat absorption could be circular: More Firmicutes means more efficient fat absorption, and a fattier diet means more Firmicutes. “Diet history could impact fat absorption by changing the abundance of certain microbes, such as Firmicutes, that promote fat absorption,” said Ivana Semova, the study’s lead author. The fact that other studies have found higher populations of the same type of bacteria in the intestinal tracts of obese humans, too, underscores the correlation between these two factors.

For those concerned with gaining weight, though, it isn’t all bad news: Scientists have found that changes in the populations of various types of bacteria in the digestive tract, including Firmicutes, are reversible. Over time, in the experiments with mice, a low-fat diet led to diminished populations of the microbes, which would then theoretically lead to less efficient absorption of fat from food.

The researchers say that a better understanding of the role microbes play in our digestion of food can help with efforts to combat both malnutrition and obesity. ”If we can understand how specific gut bacteria are able to stimulate absorption of dietary fat, we may be able to use that information to develop new ways to reduce fat absorption in the context of obesity and associated metabolic diseases, and to enhance fat absorption in the context of malnutrition,” Rawls said.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)