Behold, the First Closeup Pictures From the Pluto Flyby Are Here

From fresh-faced moons to ice mountains, these are the visual surprises that hit the ground the day after the Pluto flyby

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/bc/48bceaa5-b57a-483d-9518-6ce07688a73d/nh-plutosurface.jpg)

"I had a pretty good day yesterday. How 'bout you?" quipped a grinning Alan Stern, the mission leader for the New Horizons probe, as his team prepared to unveil the first close images from yesterday's successful Pluto flyby. The results, from five of the spacecraft's seven instruments, show that the Pluto system is weird, wonderful and packed with scientific treasures.

New Horizons zipped past Pluto on Tuesday morning, coming within about 7,000 miles of the planetary surface. The encounter lasted a few hours and involved good long looks not just at Pluto's sunlit face, its largest moon Charon and its four smaller moons, as well as a parting study of the nightside of Pluto partially illuminated by moonlight from Charon.

"New Horizons is now more than a million miles on the other side of Pluto," Stern said during a July 15 press briefing. "The spacecraft is in good health and it communicated with Earth again for a number of hours this morning." While the latest haul represents just the tip of a massive Plutonian iceberg, these early images from the mission are already yielding some startling implications.

Perhaps the biggest surprise is that Pluto has mountains of water ice towering near its equator. The peaks reach up to 11,000 feet high in a region where there are no obvious impact craters. This suggests that some geologic force created the mountains, while other relatively recent activity kept the surrounding terrain fresh and smooth. That's a shock, because until now, scientists thought that the most probable thing driving this kind of activity on icy worlds is tidal heating—the gravitational push-and-pull from a much larger orbital partner.

"This is the first time we have seen an icy world that isn't orbiting a giant planet," mission scientist John Spencer said during the briefing. "We see strange geological features on many of these moons and we usually interpret this as tidal heating … but that can't happen on Pluto. You do not need tidal heating to power ongoing recent geological activity on icy worlds. That's a really important discovery that we just made this morning. I know this is just the first of the many amazing lessons we're going to get from Pluto."

Stern emphatically agrees: "We now have an isolated small planet that's showing activity after 4.5 billion years … I think it's going to send a lot of geophysicists back to the drawing board."

An additional wrinkle is that previous observations showed Pluto covered in other types of ice, such as methane and nitrogen. Scientists had previously surmised that these ices settle on Pluto as its thin atmosphere freezes out, coating the world in a thin veneer. These types of ices are too weak to form mountains, so the new image boosts the notion that they are just frosting on "bedrock" of water ice, says Stern. But Pluto is also losing its atmosphere at a steady rate—so where is all this atmospheric material coming from?

"There must be internal activity that'd be dredging nitrogen up, like geysers or cryovolcanism," suggests Stern. "We haven't found any yet, but this is very strong evidence that will send us looking."

Not all the images are as immediately visual, but they are offering the team new clues to the complexity of the Pluto system. Today's release includes the best view yet of Pluto's farthest moon, Hydra. While more reminiscent of an eight-bit video game character than a moon, the image did help the team figure out Hydra's size: 28 by 19 miles.

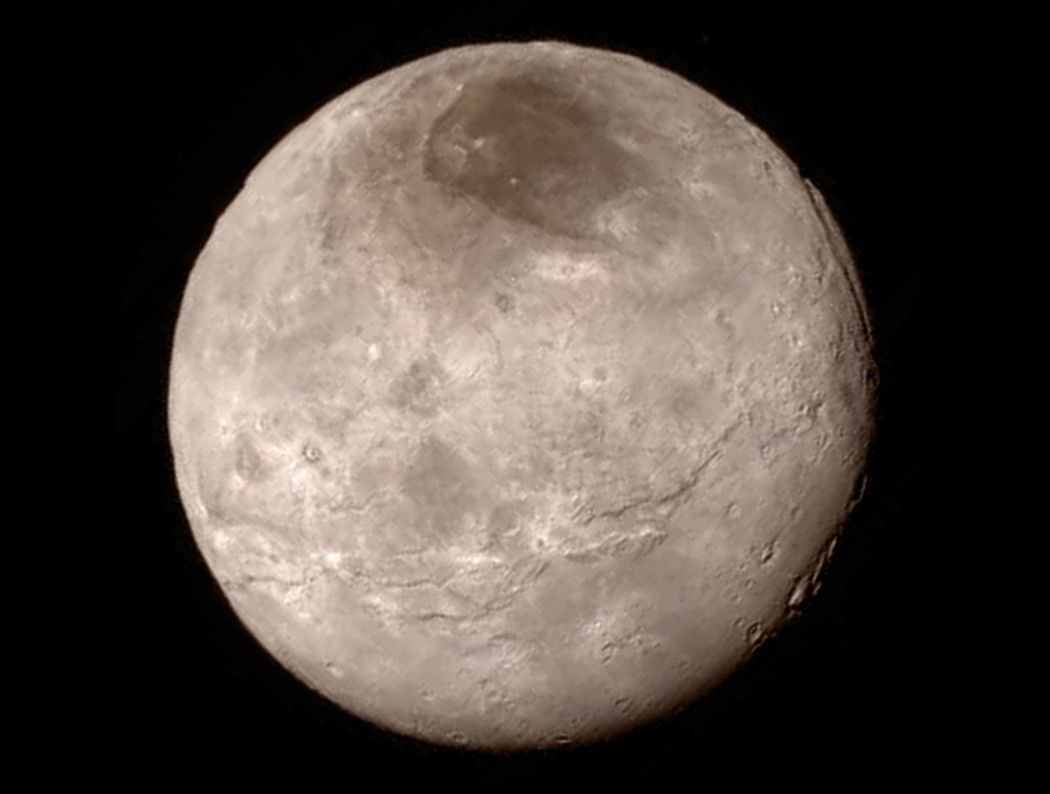

The scientists were also overjoyed to see their first high-resolution image of Charon, which shows a relatively young surface lined with geologic features and topped with a dark region informally dubbed Mordor. One striking trough stretches up to 600 miles across the moon's face, the team reports, while elsewhere a canyon cuts four to six miles deep. "Charon today just blew our socks off," said mission scientist Cathy Olkin. "We've been saying that Pluto did not disappoint. I can add that Charon did not disappoint either."