A Plague of Locusts Descends Upon the Holy Land, Just in Time for Passover

Israel battles a swarm of millions of locusts that flew from Egypt that is giving rise to a host of ecological, political and agricultural issues

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130306041137Locust-small-300x164.jpg)

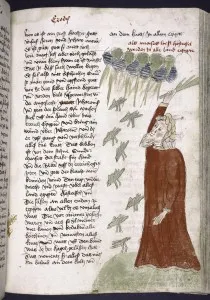

Locusts have plagued farmers for millennia. According to the Book of Exodus, around 1400 B.C. the Egyptians experienced an exceptionally unfortunate encounter with these ravenous pests when they struck as the eighth Biblical plague. As Exodus describes, “They covered the face of the whole land, so that the land was darkened, and they ate all the plants in the land and all the fruit of the trees that the hail had left. Not a green thing remained, neither tree nor plant of the field, through all the land of Egypt.”

Locusts attacks still occur today, as farmers in Sudan and Egypt well know. Now, farmers in Israel can also join this unfortunate group. Earlier today, a swarm of locusts arrived in Israel from Egypt, just in time for the Jewish Passover holiday which commemorates Jews’ escape from Egyptian slavery following the ten Biblical plagues. “The correlation with the Bible is interesting in terms of timing, since the eighth plague happened sometime before the Exodus,” said Hendrik Bruins, a researcher in the Department of Man in the Desert at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel. “Now we need to wait for the plague of darkness,” he joked.

While the timing is uncanny, researchers point out that–at least in this case–locust plagues are a normal ecological phenomenon rather than a form of divine punishment. “Hate to break it to you, but I don’t think there’s any religious significance at all to insects in the desert, even a lot of them, and even if it seems reminiscent of a certain Biblically described incident,” said Jeremy Benstein, deputy director of the Heschel Center for Sustainability in Tel Aviv.

In this region of the world, locusts swarm every 10 to 15 years. No one knows why they stick to that particular cycle, and predicting the phenomena remains challenging for researchers. In this case, an unusually rainy winter led to excessive vegetation, supporting a boom in locust populations along the Egyptian-Sudanese border. As in past swarms, once the insect population devours all of the local vegetation, the hungry herbivores take flight in search of new feeding grounds. Locusts–which is just a term for the 10 to 15 species of grasshoppers that swarm–can travel over 90 miles in a single day, carried mostly by the wind. In the plagues of 1987 and 1988 (PDF)–a notoriously bad period for locusts–some of the befuddled insects even managed to wash up on Caribbean shores after an epic flight from West Africa.

When grasshoppers switch from a sedentary, solo lifestyle to a swarming lifestyle, they undergo a series of physical, behavioral and neurological changes. According to Amir Ayali, chair of the Department of Zoology at Tel Aviv University, this shift is one of the most extreme cases of behavioral plasticity found in nature. Before swarming, locusts morph from their normal tan or green coloring to a bright black, yellow or red exoskeleton. Females begin laying eggs in unison which then hatch in synch and fuel the swarm. In this way, a collection of 1 million insects can increase by an order of magnitude to 1 billion in a matter of several days.

From there, they take flight, though the exact trigger remains unknown. Labs in Israel and beyond are working on understanding the mathematics of locust swarming and the neurological shifts behind the behaviors that make swarming possible. ”If we could identify some key factors that are responsible for this change, we could maybe find an antidote or something that could prevent the factors that transform innocent grasshoppers from Mr. Hyde to Dr. Jekyll,” Ayali said. “We’re revealing the secrets one by one, but there’s still so much more to find out.”

A swarm of locusts will consume any green vegetation in its path–even toxic plants–and can decimate a farmer’s field almost as soon as it descends. In one day, the mass of insects can munch its way through the equivalent amount of food as 15 million people consume in the same time period, with billions of insects covering an area up to the size of Cairo, Africa’s largest city. As such, at their worst locust swarms can impact some 20 percent of the planet’s human population through both direct and indirect damages they cause. In North Africa, the last so-called mega-swarm invaded in 2004, while this current swarm consists of a measly 30 to 120 million insects.

Estimating the costs exacted by locusts swarms remains a challenge. While locust swarms reportedly cause more monetary damage than any other pest, it’s hard to put an exact figure on the problem. Totaling the true crost depends on the size of the swarm and where the winds carry it. To be as accurate as possible, costs of pesticides, food provided to local populations in lieu of wrecked crops, monitoring costs and other indirect effects must be taken into account. No one has yet estimated the cost of this current swarm, though the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) allots $10 million per year solely to maintain and expand current monitoring operations.

This morning, the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture sprayed pesticides on an area of around 10,000 hectares near the Egyptian border. To quell a plague of locusts, pest managers have to hit the insects while they’re still settled on the ground for the night and before they take flight at dawn. So far, pesticide spraying is the only option for defeating the bugs, but this exacts environmental tolls. Other invertebrates, some of them beneficial, will also shrivel under the pesticide’s deadly effects, and there’s a chance that birds and other insectivores may eat the poisoned insect corpses and become ill themselves. Researchers are working on ways to develop fungus or viruses that specifically attack locusts, but those efforts are still in initial investigative stages.

Even better, however, would be a way to stop a swarm from taking flight from the very beginning. But this requires constant monitoring of locust-prone areas in remote corners of the desert, which is not always possible. And since the insects typically originate from Egypt or Sudan, politics sometimes get in the way of quashing the swarm before it takes flight. “We really want to find them before they swarm, as wingless nymphs on the ground,” Ayali said. “Once you miss that window, your chances of combating them are poor and you’re obliged to spray around like crazy and hope you catch them on the ground.”

In this case, Egypt and Israel reportedly did not manage to coordinate locust-fighting efforts to the best of their abilities. “If you ask me, this is a trans-boundary story,” said Alon Tal, a professor of public policy at Ben-Gurion University. “This is not a significant enemy–with an arial approach you can nip locusts in the bud–but the Egyptian government didn’t take advantage of the fact that they have quite a sophisticated air force and scientific community just to the north.”

Ayali agrees that the situation could have been handled better. He also sees locusts as a chance to foster regional collaboration. Birders and ornithologists from Israel, Jordan and Palestine often cooperate in monitoring migratory avian species, for example, so theoretically locusts could likewise foster efforts. “Maybe scientists should work to bridge the gaps in the region,” Ayali said. “We could take the chance of this little locust plague and together make sure we’re better prepared for the next.”

For now, the Israelis have smote the swarm, but Keith Cressman, a senior locust forecasting office at the FAO’s office in Rome warns that there is still a moderate risk that a few more small populations of young adults may be hiding out in the desert. This means new swarms could potentially form later this week in northeast Egypt and Israel’s Negev region. His organization warned Israel, Egypt and Jordan this morning of the threat, and Jordan mobilized its own locust team, just in case.

For those who do come across the insects (but only the non-pesticide covered ones!), Israeli chefs suggest trying them out for taste. Locusts, it turns out, are the only insects that are kosher to eat. According to the news organization Haaretz, they taste like “tiny chicken wings,” though they make an equally mean stew. “You could actually run out very early before they started spraying and collect your breakfast,” Ayali said. “I’m told they’re very tasty fried in a skillet, but I’ve never tried them myself.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)