Fourteen Fun Facts About Love and Sex in the Animal Kingdom

Out in the wild, flowers and candy just aren’t gonna cut it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/d5/21d52f51-bb0a-457f-8669-4afd346e85a8/brjx5m.jpg)

Dating apps have reduced the ritual of human coupling down to a swipe. Out in the wild, though, love and sex don’t come as easy. Creatures of all sorts have evolved some pretty spectacular strategies to woo their mates and ensure their genes carry on. Here are just a few examples of extreme courtship and copulation that put us tech-savvy humans to shame.

You gonna drink that?

Like humans, giraffes undergo cycles of fertility. Unlike (most) humans, giraffes will sip each other’s urine—a surefire way to tell if a female is in heat. This time-saving technique ensures that a male won’t waste energy snooping around a lady who won’t give him the time of day or is unlikely to conceive if they couple up.

A male will crane his long neck over to the female’s rump, nuzzling his head against her genitals. After she gives her suitor careful consideration (giraffes pregnancy can be a 15-month commitment), the female will voluntarily release a squirt of pee for her partner to catch in his mouth and “savor,” researchers David M. Pratt and Virginia H. Anderson wrote in a 1984 paper. In a bizarre evolutionary twist, the giraffe tongue functions a bit like an ovulation stick, sensitive enough to detect the hormones that can tell a guy if his girl is hot to trot.

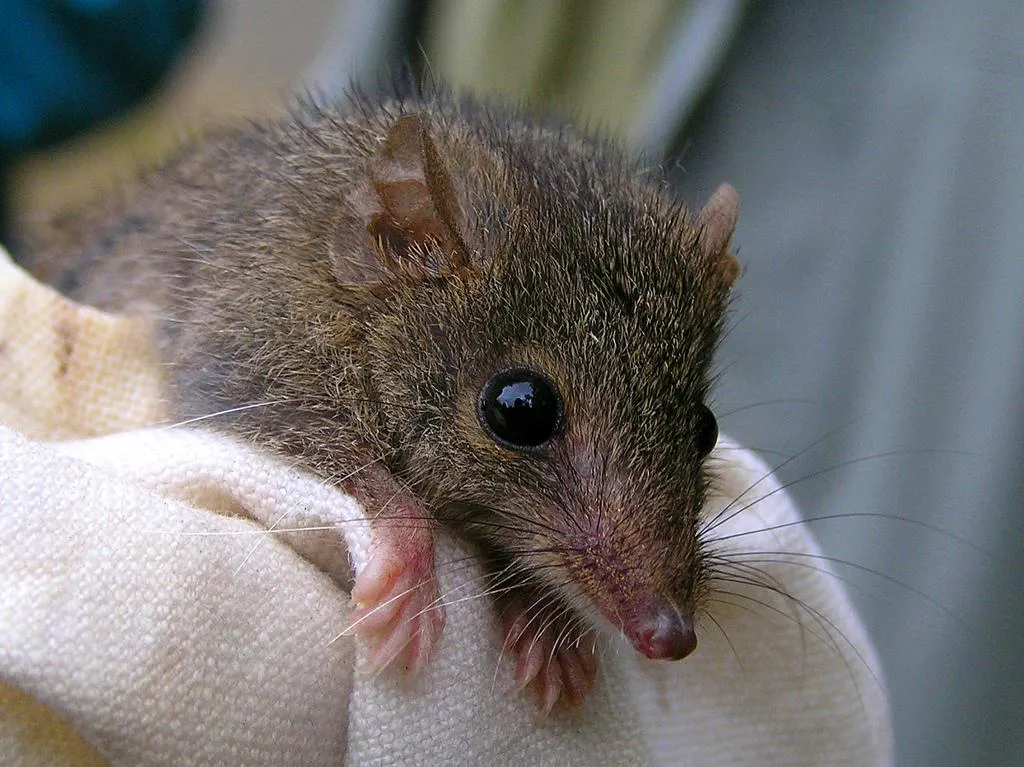

Going out with a bang

For a two- or three-week stretch in early spring, Australian forests reverberate with the sexual shenanigans of the male antechinus. These tiny, tireless marsupials can engage in a single intimate encounter for 14 hours straight. Desperate, virile and indefatigable, each of these bitty boys will mate with as many females as possible, plugging away until the fur sloughs off his skin, his immune system fails and blood pools around his organs. In a grand culmination of this fornication feat, the male antechinus physically disintegrates: He quite literally boinks himself to death, usually just shy of his first birthday.

So-called suicidal reproduction might sound absurd, but vigorous, organ-shredding sex is the antechinus males’ way of outcompeting each other in the reproductive race to father the most young. The more sperm a male churns out, the more successful he’ll be. A sexual sprint to the death is the antechinus’ one shot at passing on his genes, and he puts every second of it to good use.

Et tu, bed bug?

Here’s another wince-worthy phrase: traumatic insemination. That’s the term scientists have assigned to the stabby sex of bed bugs (Cimex species). When a male gets in the mood, he’ll mount a recently fed female (or, sometimes, male) and plunge his sharp, needle-like penis directly into her abdomen, ejaculating into the open wound (bypassing her perfectly functional reproductive tract, which is used only for outbound eggs). The sperm finds its way through a labyrinth of lymph (insect blood) to the ovaries, where it fertilizes the recovering female’s eggs.

The encounter is as violent as it sounds: Females can die from their injuries or ensuing infections. They do, however, have a few tricks to survive, including a mighty genital structure called the spermalege that bolsters healing and immunity. In some cases, the female can stop this sexual soirée before it begins by curling forward, making it more difficult for the male to access her vulnerable belly. Why this doesn’t happen on every bed bug date remains a mystery.

Who wears the penis?

Neotrogla barklice, flea-sized insects native to the caves of southeastern Brazil, are notable for their extreme sex reversal: Females carry penis-like organs called gynosomes used to penetrate the vagina-like genitals of males during copulation.

These bizarrely backwards rendezvous, in which the gynosome will siphon sperm from inside the male’s body, can last between 40 and 70 hours. Neotrogla sperm, which is chock-full of nutrients, doesn’t just fertilize the female’s eggs: It also keeps her fed during sustained bouts of intercourse.

To stabilize herself during the prolonged act of procreation, the female will anchor herself inside the male via patches of spines that adorn her gynosome. This sexual Velcro is so effective that attempts to separate barklice in flagrante have ended in tragedy, with the male torn in two, his reproductive organs still clinging to the female’s barbed member.

A kiss of death

The iconic image of the anglerfish—a deep-sea creature sporting jagged, translucent teeth and a luminescent lure to bait prey—represents only the females of this bunch. Petite, stunted and devoid of glowy baubles, male anglerfish are harder to photograph and far less interesting to look at.

Among certain species of anglerfish, like those in the sea devil (Ceratiidae) family, males are little more than sperm sacs with nostrils. Born into a world of darkness, they sniff and strain to fulfill their only life goal: find and mate with a female, detectable by a potent combination of pheromones and her species-specific glow. In some cases, the males are so poorly developed that they lack even a fully functional digestive system. Up to 99 percent of these unfortunate suitors die as starving virgins.

The other one percent don’t fare much better. Once a male locates a female, he’ll press his mouth to her flank and begin to disintegrate, fusing the pair’s flesh together. The male’s organs melt away until all that remains is little more than a pair of testes with gills. Some females can carry upwards of six males on their bodies at once, dipping into their sperm at will.

Twisted love

Cirque du Soleil performers have nothing on leopard slugs (Limax maximus). Though slow and sluggish on the ground, these slippery slime bombs get surprisingly gymnastic when it comes to coupling up.

Though the slugs are hermaphrodites, they don’t self-fertilize, and instead seek out partners to symmetrically exchange sperm (gender parity, anyone?). Upon meeting, the duo will dangle themselves from a branch or overhang, intertwining their bodies while suspended from a bungee cord of mucus. Coiled into this tight embrace, each will then unfurl an iridescent blue penis from the right side of its head. The organs swell and connect, twisting into a shimmering chandelier that acts as a pulsating conduit for sperm. Once the transfer is complete, the slugs climb back up the mucus rope or drop to the ground, where each may lay a cache of freshly-fertilized eggs.

When love lasts a lifetime

The Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis) of Hawaii often mates for life, but not always with the partner that knocked them up. On the island of Oahu, males are scarce, and single-parent females struggle to cope with the energy-demanding task of incubating eggs and raising the chicks that hatch from them. So the majestic birds came up with a solution: Here, lady albatrosses will shack up to co-parent, sometimes cohabitating for years at a time, researchers have found.

Albatrosses only raise one chick a year regardless of the sex ratio in their couple, and on average, same-sex parent couples produce and raise fewer babies than male-female pairs. But given the alternative of no partner at all, this strategy seems an excellent compromise. As the researchers explain, “in situations where males are in short supply, female-female pairing in the interim appears to make the best of a bad job.”

Lousy with lust

The name “tongue-eating louse,” as horrifying as it sounds, barely begins to do Cymothoa exigua justice. This marine parasite isn’t satisfied with consuming the tongue of its host—it actually replaces it. And that’s after a sex change during the process.

Let’s back up. First, a cadre of juvenile lice will infiltrate the gills of a hapless fish and mature into males. Upon reaching adult size, at least one will transform into a female, ostensibly to even out the sexes. The newly minted lady louse will then wriggle up the fish’s throat, anchor herself to her host’s tongue, and slowly begin to drain the organ of its blood.

The poor fish’s tongue withers into a useless nub, leaving the mouth vacant for the louse itself to physically take its place, helping its host move food around its mouth and grind big morsels down to size. During its off hours, the bug contentedly feed, relaxes and bumps uglies with the gill-dwelling males.

Tag, you’re it

Some of the world’s most riveting duels break out on the ocean floor, where you’ll find hermaphroditic flatworms parrying with their penises. This phallic form of fencing is a time-honored, high-stakes mating ritual—and the loser must bear the burden of fostering the couple’s fertilized eggs.

Each worm boasts a pair of penises, which resemble white, thin-tipped daggers that teem with semen. The goal is simple: Inseminate your partner before you get pricked by its prick. Flatworms have plenty of incentive to keep their sparring skills up to snuff.

I am whiptail, hear me roar

Somewhere along the meandering path of evolution, a branch of the reptilian tree decided it was fed up with males and their worthless sperm. So it got rid of them entirely. Today’s New Mexico whiptail lizards (Aspidoscelis neomexicanus) are one of several all-female species that reproduce without male input. Instead, these lizard ladies clone themselves in perpetuity, producing eggs with twice the typical number of chromosomes that can develop into embryos without being fertilized by sperm. (They do, however, still show some proclivities for mating behaviors, with females mounting females—an act that might boost fertility.)

New Mexico whiptails actually represent a remarable evolutionary feat: Their lineage came about via the union of two separate species, the little striped whiptail and the western whiptail. Hybrids like these are often unable to reproduce (think mules), but in blending the traits of their parents, New Mexico whiptails inherited a diverse genome, and are able to carbon copy it over and over. Should their environment change, though, they could someday be in trouble: Without another genetic pool to dip into, these lookalike ladies risk dying out in one fell swoop.

Once again, with feeling

Male white bellbirds (Procnias albus) are not ones for subtlety. When they’re feeling frisky, they’ll sidle up to a female, inhale deeply and scream directly into her face. Their calls are the loudest ever recorded in the avian world, peaking at roughly 115 decibels, the approximate equivalent of shoving your head into “a speaker at a rock concert,” researchers have said. While belting out multi-note ballads, the males will strut around and whip their wattles (fleshy outgrowths that dangle over their beaks) so vigorously that they sometimes slap their dates in the face.

Females don’t seem to mind the punishment. In fact, researchers suspect they’re pretty into the whole mess—an attraction that’s driven the evolution of such an extreme, possibly even deafening, trait. Perhaps the shrieks are the males’ way of boasting their physical prowess. Or maybe these boisterous boys just don’t know when to shut up—and the ladies know not to expect any less.

Watch out boy, she’ll chew you up

For the male praying mantis, mating can be deadly. That’s because the female of the species is, quite literally, a maneater. Male mantises frantically pursue a mate just before winter sets in, when they are facing an imminent, slow death. Perhaps that’s why they don’t seem to mind the second option: Being decapitated and eaten alive mid-fornication.

Why do the female bugs turn cannibalistic mid-shag? Sex takes a lot of energy, and devouring their partner is a great source of nutrition that boosts her ability to produce fertilized eggs. She’ll start with the head, because male mantises can actually keep at it for a while without it. (In one documented case, a female ate her mate’s head before they got busy and he still did the deed.)

As a male perishes, his abdomen spasms, pumping sperm into the partner and thus increasing the likelihood of mating success. When it’s all said and done, the female gobbles up her mate’s carcass, his lifeless body. A gruesome way to go, but at least he didn’t die cold and alone?

Oh, it’s the safety dance!

We can dance if we want to, but male peacock spiders (Maratus species) dance for their lives.

Like their avian namesakes, these gorgeous boys have rainbow-hued, light-reflecting patterns adorning a fan-like appendage on their thoraxes—but that’s not enough to impress females. These ladies want to see their potential mates shake it like a Polaroid picture—and if it’s not up to par, prepare to die, sir.

The male spiders raise their vibrant fan in the air and give the performance of a lifetime in hopes of, well, getting laid. The female spider will chase him and lunge at him, each time threatening death, until she is finally impressed with his routine (or kills him out of sheer disappointment.) This foreplay ritual can last up to 50 minutes. In the face of death, that’s one safety dance worth the effort.

Promiscuous squid

Squid aren’t picky when it comes to pleasure—especially not the fierce Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas). Nicknamed the jumbo squid, these cephalopods can reach up to six feet in length and 110 pounds. They illuminate themselves with flashes of red and white using bioluminescence. Because of their aggressive nature, they’re sometimes called “red devils.”

But maybe they should be called cupid because they shoot their arrows, or rather sperm-packed spermatophore capsules, all over. Humboldt squids are the sixth species of squid known to engage in same-sex sexual activity as documented in scientific literature for the first time last year. These guys pretty much abide by a “live fast, die young” mentality when it comes to mating, and tend to go for quantity over quality.

That’s essentially why scientists think the cephalopods wind up mounting other males so frequently. They pretty much have nothing to lose by hooking up with both males and females because their bodies make sperm throughout their lifetime and they have 300 to 1,200 spermatophores locked and loaded at any given moment.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)