These Contest-Winning ‘Fairy Tales’ Might Be Bleak, But They Are Topical

Blank Space’s fifth-annual competition plays with everything from fake news to gravity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/68/1868eb23-ae2d-49b0-a80d-5b1d377931c1/fairy-tale.jpg)

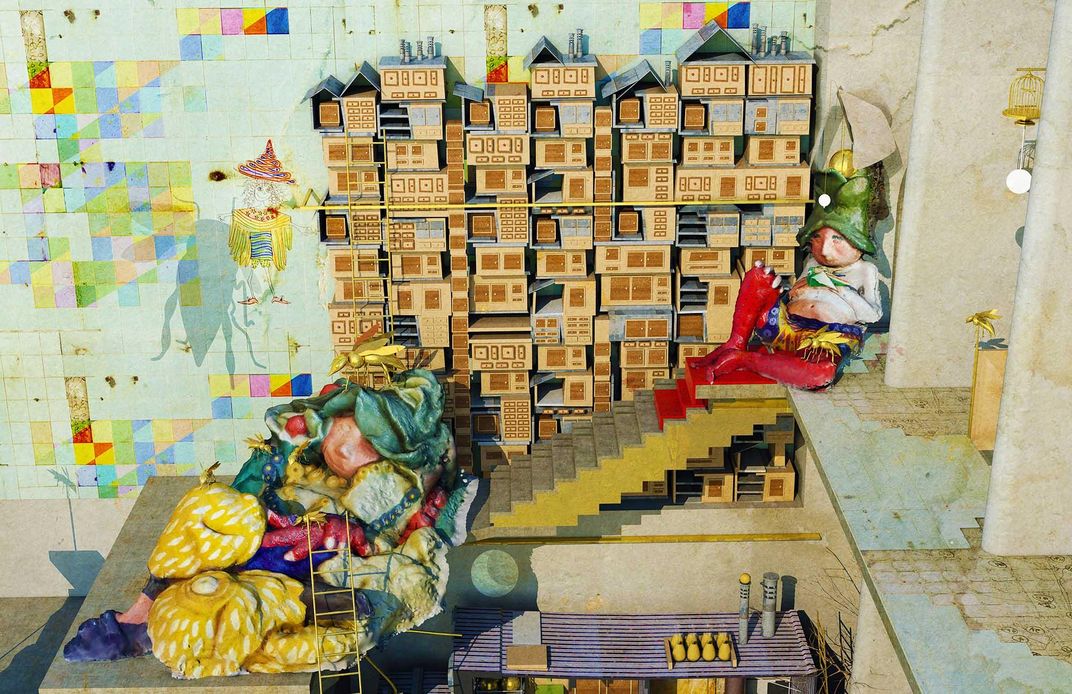

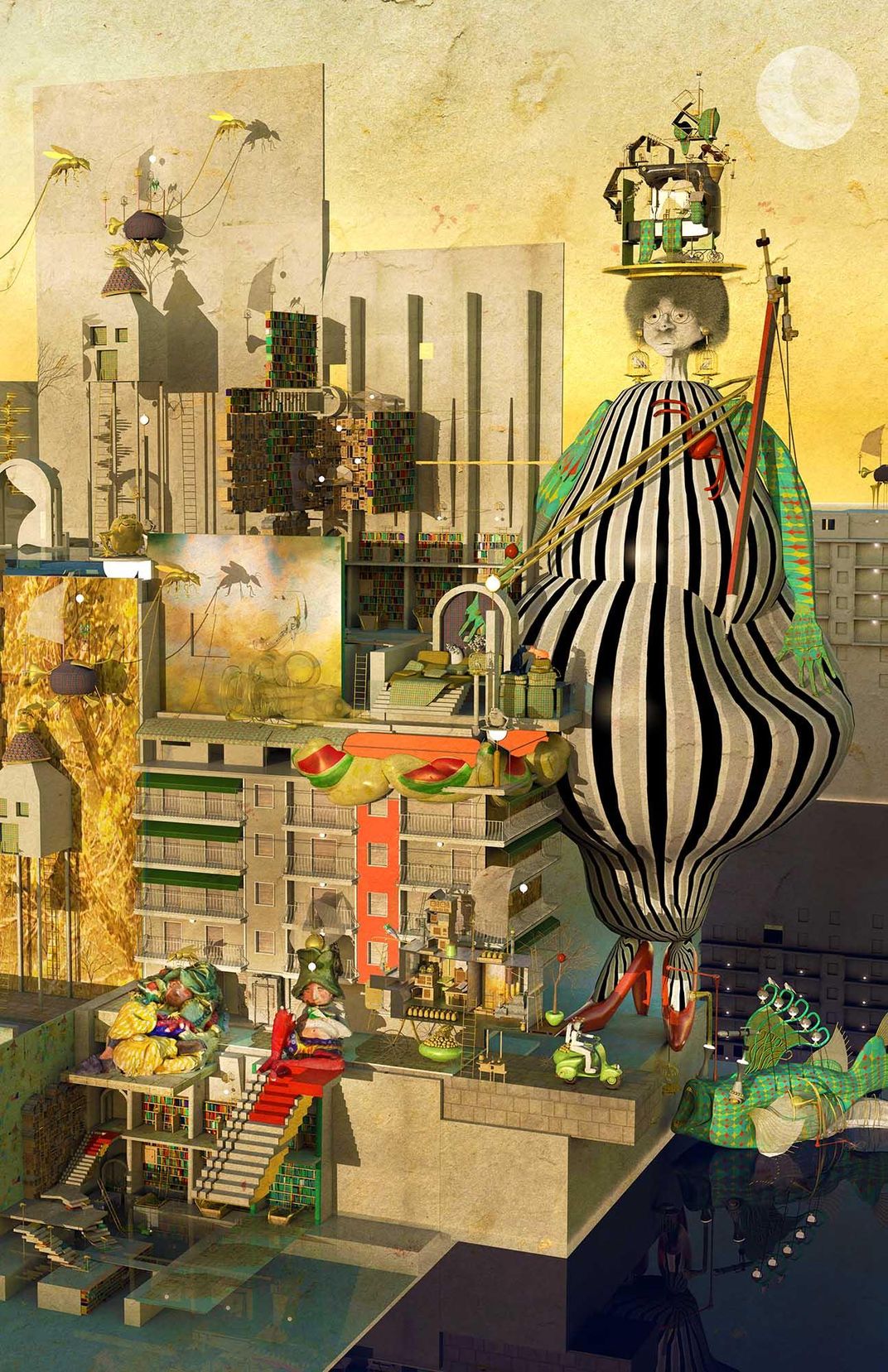

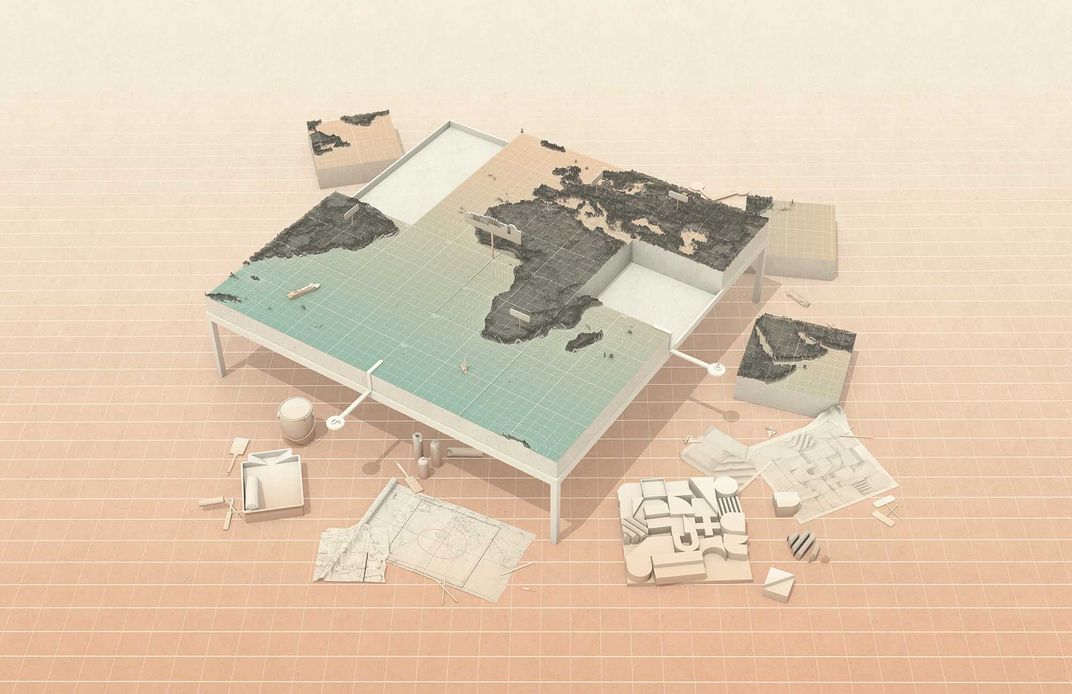

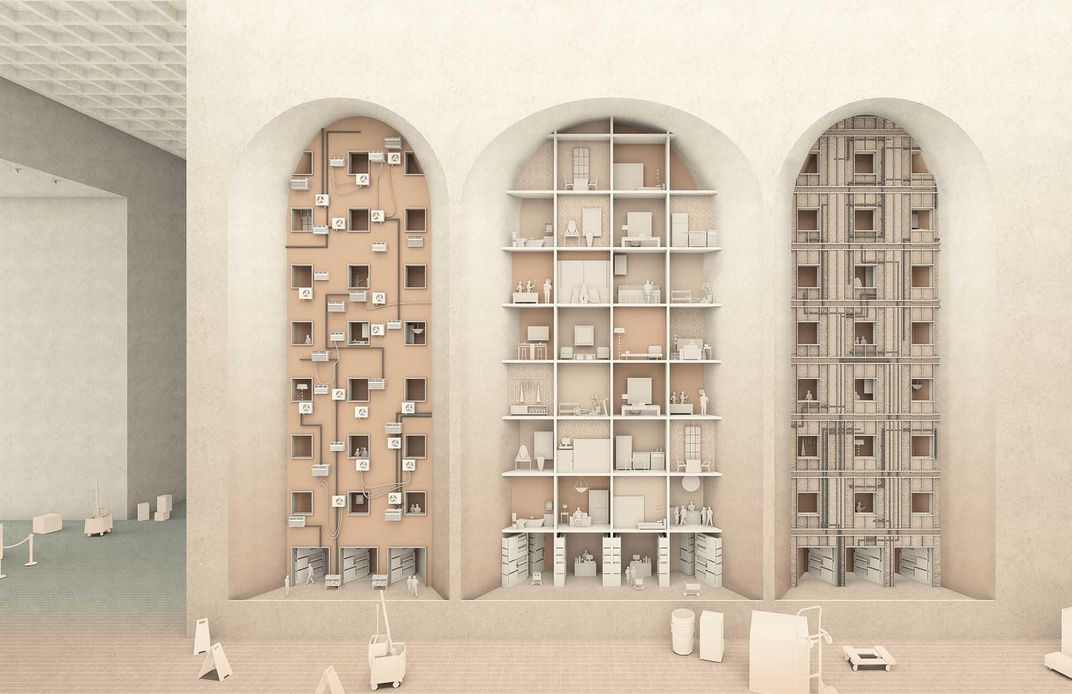

In the fairy tale, Beijing is reimagined as a city literally divided by boxes.

The rich travel from one big box to the next, and the poor, who cannot afford boxes, live in precarious towers of suitcases set to be torn down.

One day, Su, a journalist, decides to report on the forced removal of the poor from the city. When her editor refuses to run the piece, she lets a friend post the article on her behalf on his highly trafficked personal media account. But after the story is published, she realizes her writing has been twisted to serve the purposes of his audience, who are only looking to read what they want to hear.

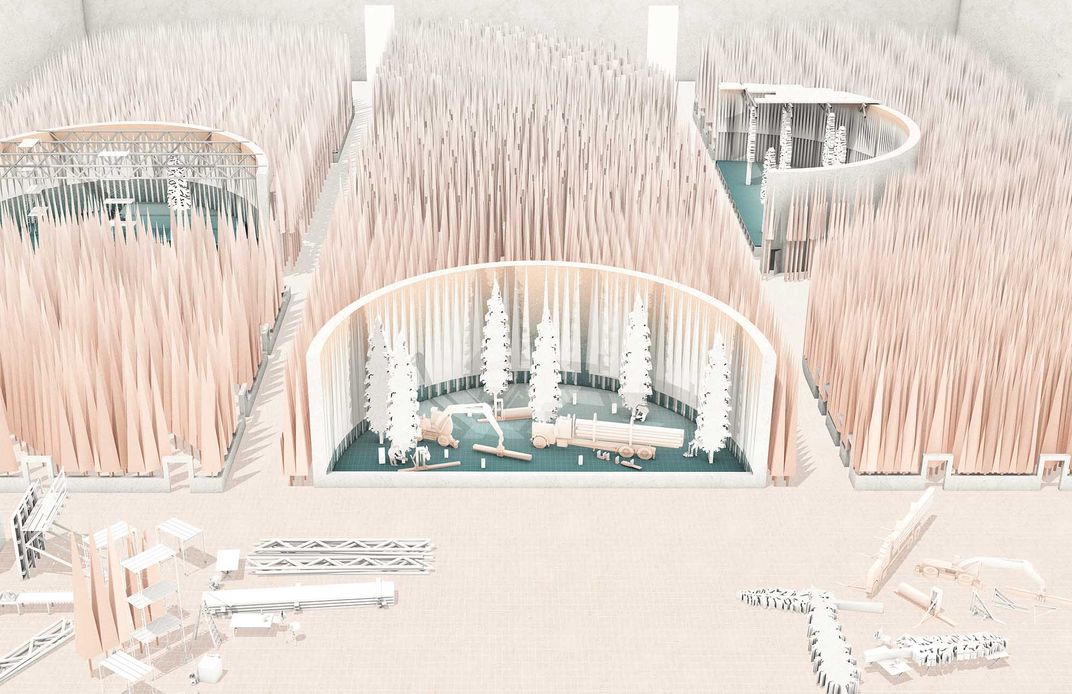

The fake news fable, titled “Deep Pool That Never Dries,” and its accompanying smoggy, dystopian illustrations—the work of Louis Liu, an architectural designer, and Senyao Wei, a writer and editor—nabbed first prize at this year’s “Fairy Tales” competition, run by the online architecture platform Blank Space, in partnership with the National Building Museum, ArchDaily, Archinect and Bustler.

The annual competition, now five years running, is intended to provoke new conversations about architecture, according to Blank Space’s co-founders Matthew Hoffman and Francesca Giuliani. Over the years, architects, designers, writers, artists, engineers, illustrators and others have tried their hand at their own original fairy tales, submitting the required five pieces of artwork and a narrative short story. This year alone, more than 1,000 applicants from 65 countries sent in pieces by the January 5 deadline.

Liu and Wei’s submission is a fairy tale inspired by real events. In late 2017, a deadly fire broke out killing 19 in a cramped apartment building on the outskirts of Beijing, where migrant workers from rural China live cheaply, renting rooms for a few hundred yuan a month. China’s internal migrants are classified based on the state’s controversial Hukou or household registration system, which labels citizens as urban or rural based on their registered birthplace, a designation that guarantees urban citizens certain privileges and exacerbates a wealth divide in the country.

Following the fire came a campaign to evict thousands of internal migrants from housing designated as unsafe and overcrowded, leaving many homeless in the bitter Beijing winter. News of the decision spread like wildfire on Chinese social media, with one open letter condemning the evictions as “a serious trampling of human rights.”

Liu and Wei were among those who watched with rapt attention as details of the story emerged. Which sources were reliable? The couple wondered. Who could be trusted?

Those questions morphed into their dreamlike submission, which opens up a conversation about how fake news is considered throughout the world. The Collins Dictionary “Word of the Year” for 2017, “fake news” as defined by the dictionary, means “false, often sensational, information disseminated under the guise of news reporting.” The term takes on different meaning in China, however, where official media is controlled by the government. While social media has become an alternative outlet for information, without editorial standards, stories with clear biases, in addition to government-fabricated pieces, can make it hard to separate fact from fiction on the internet.

The Beijing-based team decided to take on fake news through the lens of architecture, which they hoped would prove a less polarizing platform. “Architecture itself is a medium of the city,” Liu says. “People forget that they live in a city, that they are part of this reality, because now people are more into the reality of the virtual world.”

Considering the power of virtual space in comparison to physical structures, their story ends with Su returning to the site of the demolished dwellings. There, she recalls Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu’s meditation, "All tangles untied, All dust smoothed. It is like a deep pool that never dries." The final line of the story reads, “The city itself is the truth, but it accepts our lies.”

A jury of more than 20 leading architects, designers and storytellers, including Bjarke Ingels, Jenny Sabin, and Roman Mars, judged the Fairy Tale competition’s submissions, and National Building Museum curator Susan Piedmont-Palladino announced the three winners, a runner up and nine honorable mentions live at the museum late last week.

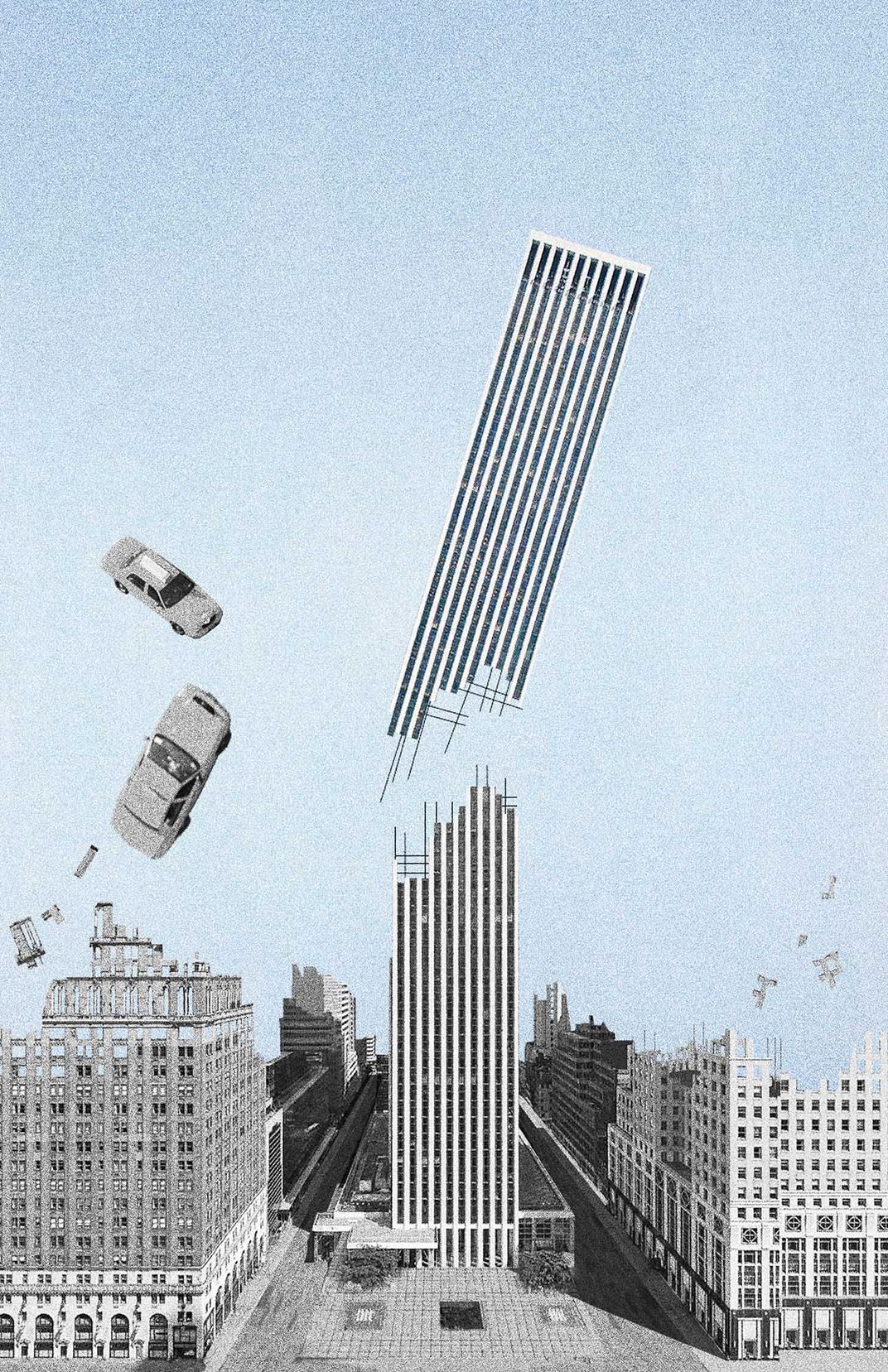

Sasha Topolnytska, an architectural designer at Deborah Berke Partners Architecture based in New York City, took second place for her submission “Ascension,” which is set in a future where the world loses gravity as a punishment for humanity’s abuses. Architect and illustrator Ifigeneia Liangi, who is pursuing PhD research at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, rounded out the top three with “The Paper Moon,” a magical tale set in her native Athens, which shakes off traditional trappings of good and evil.

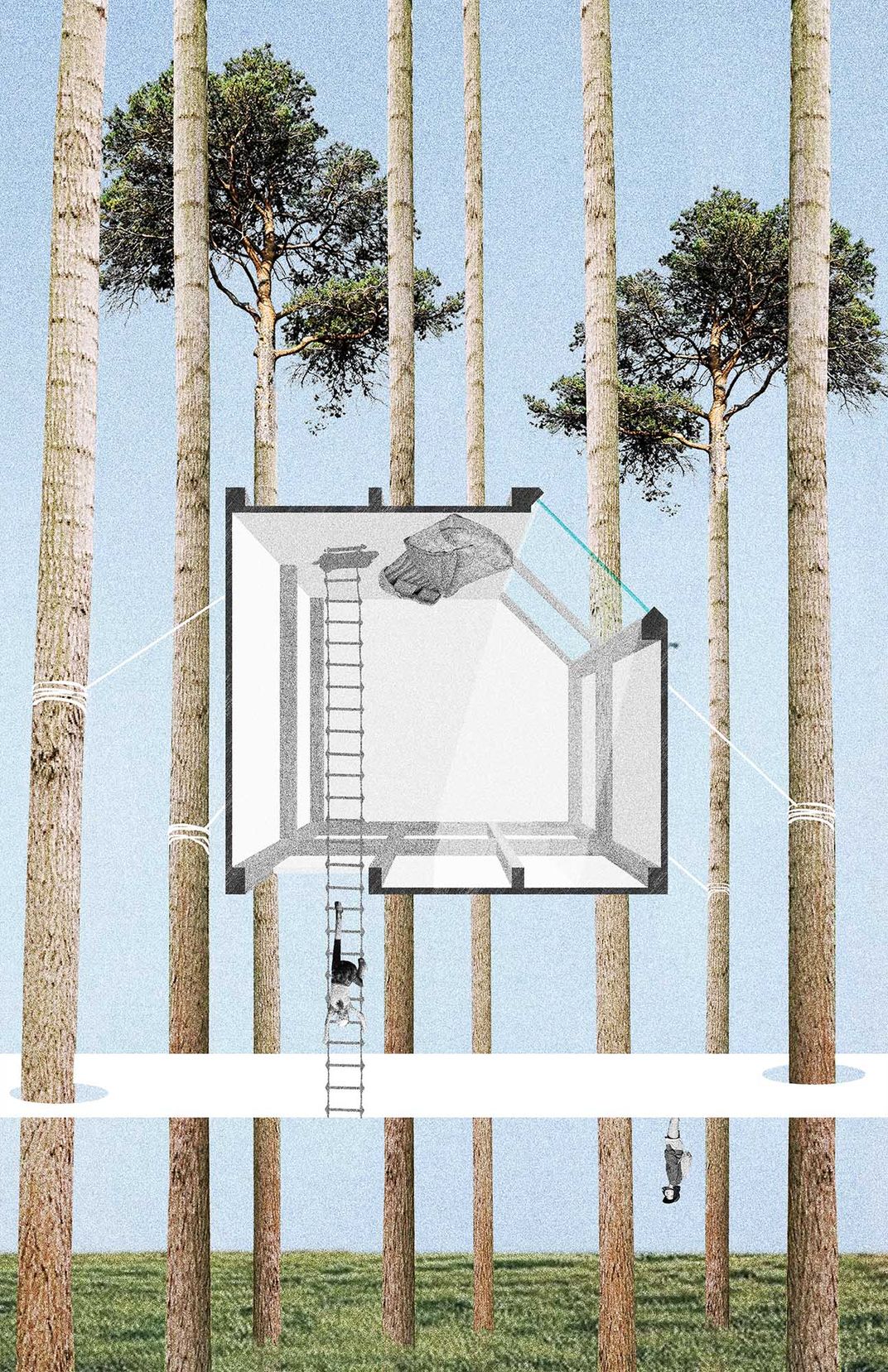

Perhaps in response to perceptions of the world today, this year’s submissions appeared somewhat more dystopian than last year’s, where Ukrainian architect Mykhailo Ponomarenko took first for his submission "Last Day," which inserted science fiction-like structures into ordinary landscapes.

The National Building Museum’s director Chase Rynd, who has served as a judge for the competition for the past two years, says he, too, noticed a darker tone in this year’s entries, but also observed an undercurrent of hope even in the bleaker pieces, something he believes feeds the competition’s well of ideas going forward.

“In my experience architects are intrinsically hopeful,” says Rynd. “I think you sort of have to be if you’re building something that’s going to last for years, decades or centuries.”

Back in October, Hoffman and Giuliana spoke to this optimism of architects in an interview with WorldArchitecture.org marking the competition’s return. The idea, they said, was “to inspire creatives and designers at a time when the world is struggling to distinguish fact from fiction — when real news is often grim and scary, and 'fake news' sows discord and diffidence."

Little did they know, the winning fable would address fake news head on.