King of the Playground, Spencer Luckey, Builds Climbers That Are Engineering Marvels

The 46-year-old architect and his crew build multi-story climbing structures for museums and malls around the world

Spencer Luckey wants each of his climbing structures to be like a really good Taylor Swift song, something that people can size up and appreciate immediately. "I am always trying to make stuff that will get the biggest audience," he says.

For the last decade, Luckey has been at the helm of a family business, Luckey Climbers, that his father, Thomas Luckey, founded in 1985. His sculptures—multi-story mazes for scurrying children—are found around the world, from the playground of his former elementary school to museums, malls, even an IKEA in Moscow.

If his greatest hits are museum climbers that complement the subject matter in surrounding exhibits, then "the mall jobs," he says, which are more about color and composition, "are little ditties."

***

I met Luckey at his studio in New Haven, Connecticut, on a warm August morning. Walking down Chapel Street in the city’s Fair Haven neighborhood, you can easily miss it, but behind a garage door is a 12,000-square-foot workshop.

The space is much like I imagined it. Inside, there is a steel fabrication studio on the ground floor with welding equipment, a forklift and monstrous metal helices. The twisted steel pipes are bound for indoor playgrounds at the Clay Center for the Arts and Sciences of West Virginia and a mall in Skokie, Illinois. Upstairs, staff use a design studio, woodworking tools and a pungent spray booth for painting and applying other finishes. There is also a dusty ping-pong table and other odds and ends. Against one wall stands a giant statue of Alvin the Chipmunk that one of Luckey’s employees fished out of a dumpster in Belfast, where they built one of their largest climbers to date.

We are in his design suite, a room with computer stations, a scribbled-on white board, and worn floorboards transplanted from his father’s old shop, talking about the company’s 30-year history. To start at the true beginning, he takes me just outside, to a shelf full of wooden cars, a sled, a rocking horse and models of merry-go-rounds and funky staircases, all made by his father.

“I actually think it all started with this car,” Luckey says, pointing to a wooden ride-on buggy he was gifted when he was six or seven years old. “He got a big kick out of making it, and he realized that it didn’t have to work perfectly for a kid to totally get into it. The kid would use it in any old way. It sort of freed him from all of the practical constraints of being an architect.”

Thomas Luckey, a graduate of Yale’s architecture school, made elaborate merry-go-rounds until an art philanthropist offered funds for him to build his first indoor playground in the Boston Children’s Museum in the mid-1980s.

“He was totally obsessed. He built this in his living room,” Luckey says, showing me a picture of the topsy-turvy climber.

With that first one, Thomas sort of codified the rules for what a Luckey Climber would be. It is a vertical, caged-in maze for children to climb. Ranging from ten to upwards of 50 feet in height, the climbers contain anywhere from 16 to 135 platforms to ascend. Thomas stipulated that there be no reaches greater than 20 inches, and only so much headroom.

“If you can’t stand up, then you can’t fall down,” says Luckey. “In other words, try to keep them on their knees.”

Playing on a Luckey Climber mirrors other activities, such as tree climbing, that some researchers believe help foster critical cognitive skills. Psychologists Tracy and Ross Alloway with the University of North Florida have found that climbing a tree can benefit working memory, or the processing of incoming information. “What hand are you going to put on the limb? Where are you going to put your foot?” Ross asks. “All those different elements require mental processing.” When the husband and wife team published their research last year, Ross had said that doing activities that are unpredictable and that require conscious decision making could help individuals’ performance at work or in the classroom.

After the Boston Children’s Museum, jobs sprung up around the country, in Winston-Salem, Tampa, Pittsburgh and Memphis. Thomas would build a model for a client, and then the client would make suggestions or approve it, and mail it back. From the model, Spencer, even before graduating from Yale’s architecture school himself, would help his father and others build the full-scale climber.

Eleven years ago, Thomas suffered a fall and became a quadriplegic. In the aftermath, he was trying to manage a job in Illinois from his hospital bed. Spencer took his laptop and an extra monitor to his father’s hospital room, and together, they designed the model for the client.

With the accident, the future of the business was called into question. But Spencer sold the job and assured the client of his confidence in his ability to carry on, while also opening the doors to a whole new way of working: digital fabrication.

“I had always thought if we could just kind of modernize it a bit, give it some jet-age sensibilities, we could make this thing really sail,” Luckey says.

In a bumpy transition, Spencer took over the business. His father died from complications of pneumonia in 2012, at the age of 72. These days, at any given time, Spencer has more than a dozen climbers in the works, from proposals to installations. He is able to make detailed computer models that reduce error, cut huge hunks out of the guesswork, and allow for even more complexity.

***

Luckey led me over to Charles Hickox, a designer who makes all of the digital renderings of the climbers. On his computer screen is the space-themed climber for the Clay Center in Charleston, West Virginia. The structure consists of twisting helices and platforms with images of the Orion Nebula on their underside.

“As an artist, you want to be an entertainer,” Luckey says. “People love seeing people perform outrageous feats.”

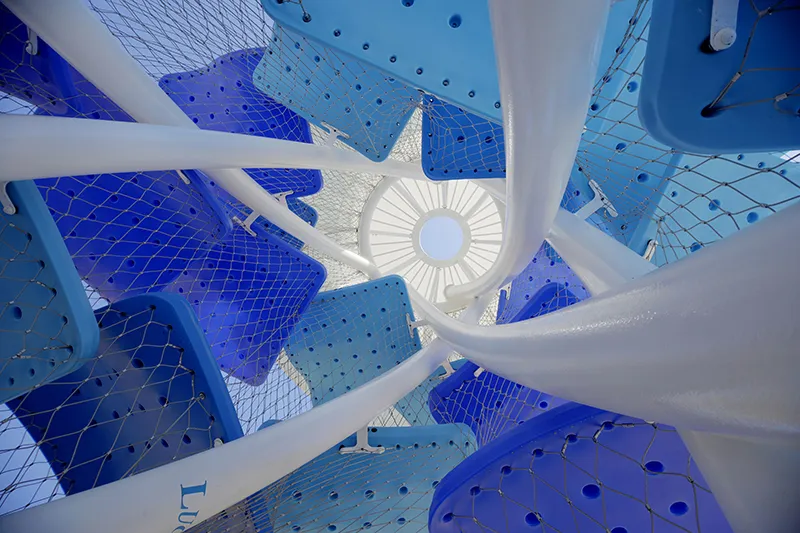

For each climber, Luckey’s palette is the same: pipes, platforms, cables and wire netting. But how he combines these materials is part whimsy, and part geometry. He’s modeled climbers off of the yin yang symbol, a dragon, palm trees and a Burj Khalifa made out of bendy straws. He often adds drama by projecting lights on them.

“You get to this point where you grope around in the dark on the design,” Luckey says. “Then you find the volume knob and just want to turn it up.”

Many of his designs boast staggering engineering feats. At the Providence Children’s Museum, for example, Luckey built an outdoor climber that rests entirely on a little ball, with none of the platforms touching the structure’s central steel pipe.

“That may not seem like any kind of achievement to an outsider, but in the climber world this was a revelation,” says Luckey.

In one of his most complex endeavors, Luckey built a climber at the Liberty Science Center in Jersey City, New Jersey that cantilevers off the second floor into a multi-story atrium. The structure is a giant suture curve, the same shape as the stitches on a baseball.

“It couldn’t touch the floor or the ceiling,” says Luckey. He knew he had cinched the project when the lead at the Liberty Science Center said, “So you just step over the edge?”

“That was like the ‘look mom, no hands,’” Luckey says. “Everyone along the way kept saying you should really just have a tension cable coming down. There are a zillion simpler solutions, but I kept pushing to make it as illogical and pleasurable an object as possible.”

Luckey is particularly fond of his science-themed climbers for museums. Designing a structure that’s somehow suggestive of a scientific concept, he says, pushes him in a much richer direction. The work is satisfying. “There is a chance that you will teach somebody something,” Luckey says.

Perhaps the most overtly scientific one is the “Neural Climber” at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. In a dark room with a vibrant light show, the climber has a metal frame and round glass platforms, positioned like stepping-stones for kids. The glass is etched with web-like neuron patterns, to make for a no-skid surface.

“I thought the reflection and transparency were cool analogs for intuition and contemplation and all of those brain functions,” says Luckey. “I also liked it because you have to stand on glass. Your mind sort of says, ‘Don’t do it.’”

For the Witte Museum in San Antonio, Luckey proposed a “digestive tract” climber. Each of the panels, or steps, is a TV screen. When you look up at it from below, the screens show footage from actual endoscopies. “It’s gorgeous in there,” he says.

The museum hasn't moved forward with the plan. Still, Luckey says, “This is so over the top and unruly that it could be really great.”

***

Peter Fox has known Luckey since elementary school and helped Thomas Luckey in the company's earliest days of building merry-go-rounds.

“I learned a lot from Tom about keep hitting the same note and eventually you have these revelations. You can see how it evolved,” says Fox, of the merry-go-round models. “Same with the climber. It’s just evolved. Now, we’re all just giddy with pride because all of our details are so worked out.”

Spencer Luckey agrees: “We’ve kind of gotten beyond the technical problems, and now it is just play.”

Luckey offers to drive me to the Foote School, a private K-9 day school in the Prospect Hill neighborhood of New Haven. Luckey attended the school, where the only two Luckey Climbers in Connecticut are found. When we get there, we first inspect Thomas Luckey’s, built in the late 1990s. It has a rippled roof, wavy pathways within it, and a spiral staircase in the center.

“This is my version,” says Luckey. Across the playground is his more modern take. Built in 2014, the climber, encircled by a white, steel ring, has bright green Pringle-shaped platforms. It is certainly not your average playground.

“This is just a theory,” Luckey says, “but kids look at the castles and pirate ships, and they go, ‘Well, do I have to be a pirate to go in the pirate ship? I kind of feel like being a bad guy or having a tea party.’”

His idea, in no small part, is to enable that kind of freedom inside his climbers, without excluding anyone.

“Kids are just constantly looking up. They want to shed their kid baggage and get some authority,” Luckey adds. “Part of the idea is to enable that and give them a proper voice that doesn’t pretend to be something that it isn’t.”

It’s his hope that a 10-year-old won’t look at this climber and think it’s too kiddie.

“They might look at this and think, that looks like a good time,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)