In Norway, an Ambitious New Standard for Green Building Is Catching On

A coalition called Powerhouse is designing buildings that produce more energy than they use in their entire lifecycle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f7/f8/f7f8f896-308f-473c-9c14-3443e7548c68/svart.jpg)

In Drøbak, Norway, there’s a little school that’s one of the most unique — and possibly the greenest — in the world. On top, solar panels face the sun at a 33-degree angle, and beneath, energy wells tap geothermal energy. This spring, students, for the first time, attended the Powerhouse Drøbak Montessori lower secondary school, which claims to be the most efficient school in Norway. It is also the most recent building completed by a coalition of architects, engineers, developers and designers called Powerhouse.

“We have a mission to make every building energy positive,” says Rune Stene, director of technology at Skanska, a contracting firm that is part of Powerhouse. “That means that we want to tear down barriers to the industry, and to the players in the industry, and to be a showcase that we have the technology, we have the knowledge, and it’s possible to do it right now.”

Powerhouse is made up of some familiar names. The internationally renowned Snøhetta does the architecture. Entra is a real estate company, Asplan Viak a real estate firm, and Zero Emission Resource Organization (ZERO) is a non-profit foundation. Together, they’re the Captain Planet (“your powers combined!”) of energy-positive building. Their mission: to build buildings that provide more power over the course of their lifetimes than they cost to build, run and demolish.

“To be able to design the buildings that can produce that much energy, that accounts for all the lifetime energy, the design has to change from form follows function to form follows environment,” says Stene. “So you see at least in the new build projects, a different shape on the building. That’s not because it’s Snøhetta that are the architects. It needs to be that way to harvest as much sun as needed for energy production.”

So far, Powerhouse as a group has retrofitted one building in addition to the school, and is partway through the construction of its first purpose-built office building. Hung up at first by regulations, Powerhouse settled on two old office buildings and renovated them into one in 2014. They stripped the ediface down to its concrete frame and rebuilt it, naming the project Kjørbo and reducing power needs by 90 percent thanks to shade screens and other passive temperature controls. The newer, partially-completed Brattørkaia, a compact, angular, 172,000 square-foot office building, is rising now on Trondheim’s waterfront.

Powerhouse isn’t a standard in quite the same way as LEED, or the longer standing BREEAM certification. According to Brendan Owens, an engineer in technical development for the U.S. Green Building Council, which administers LEED, a LEED certification depends on six key areas — location and transport, sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, materials and resources, and indoor environmental quality.

BREEAM levies ratings based on several criteria, similar to LEED. However, unlike Powerhouse, which requires energy production, BREEAM is concerned more with energy efficiency. While Powerhouses seek BREEAM certification, says Stene, their design prioritizes energy. “LEED and BREEAM would cover a broader aspect of environmental issues,” he says. “The Powerhouse concept is entirely focused on energy and climate. That is because it will be the climate that kills us at the end of the day.” While there are other groups building energy-positive buildings, none have taken the full life-cycle approach, accounting for construction and demolition the way Powerhouse does.

To market a building as a Powerhouse, the design must meet a strict definition of energy-positive. It must take into account every stage of the lifecycle, from transport of materials to construction machinery to steel and aluminum production, and even its eventual demolition. The process and materials must be monitored, and at least two of the consortium must be involved in the project. Part of the equation is constructing a building that is as efficient as possible, and most of the rest of the energy is supplemented by solar panels. It’s possible, though challenging, to make such a venture profitable, says Marius Holm, managing director for ZERO.

“If we want to achieve really green buildings, we need to accept that building design or architecture may be influenced by the environmental standards we set,” he says.

Such a standard isn’t feasible in some places, points out Owens. “For certain types of building, this is not a realistic idea,” he says. A dense, urban environment may not offer enough space to implement some of the design elements seen in current Powerhouses. But even if builders can’t make net energy positive buildings, they still can have an impact.

“Powerhouse is useful because it sets such a high, stringent bar. But it shouldn’t be that people are assuming that if they don’t strive to that level of performance that nothing that they do matters,” says Owens. “Just ‘cause you’re not running a full Ironman doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t get off your couch and run a 5k.”

And people are following Powerhouse’s lead, either explicitly, as Harvard’s energy-positive HouseZero, which was built with help from Powerhouse consultants, or implicitly, by setting their heights high, aspiring to elements laid out in Powerhouse buildings without being fully energy-positive. Powerhouse itself seeks to expand abroad, and is beginning to look at ways to integrate smart technology, and even implementing similar standards at the neighborhood scale.

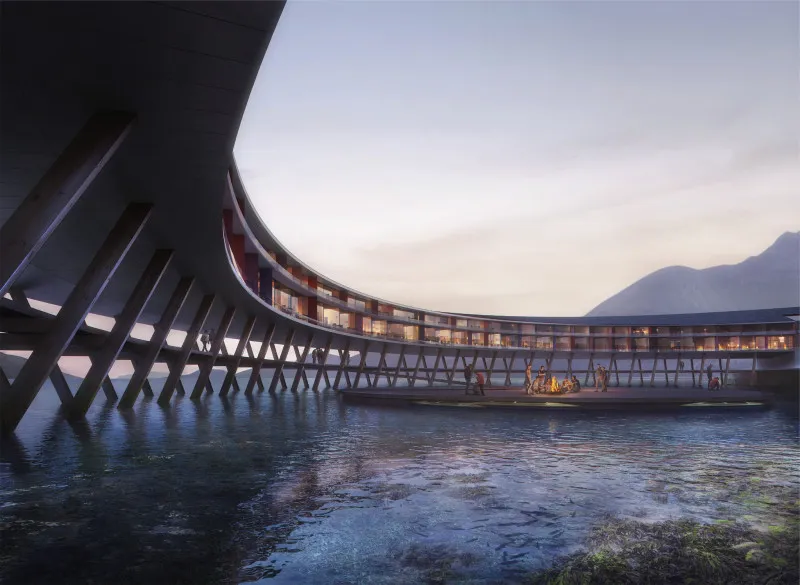

In the immediate future, the group is constructing a hotel, mostly of wood, near a glacier in the Arctic Circle, close to Norway’s Bodø and Lofoten. Called Svart, Snøhetta has released renderings of the round building, which will sit suspended over the water of a fjord. It’s a challenge on several levels. Hotels require more hot water, which must be factored in, and its location in the distant north means heating is hard and daylight sometimes scarce.

“Our ambition is to continuously push the borders for what the building industry considers possible,” says Holm.