In an Era of Superstorms, This Exhibit Captures Our Shifting Relationship with the Earth’s Rising Seas

“Sink or Swim” shows how we’re learning to be smarter and more resilient in our response to increasingly unpredictable oceans and rivers

It’s been a tough century for people living along the world’s coastlines. The combination of rising seas and catastrophic storms—from Hurricane Katrina to Indonesia’s 2004 tsunami to Tropical Storm Sandy—has not only brought horrific levels of death and destruction, but continues to raise basic questions about the relationship between humans and the sea.

Has our faith in technology as the way to conquer nature made us increasingly vulnerable to its unpredictability and destructiveness? Do we instead need to learn how to use nature to help us reduce its threats? Is the key to the future of this relationship our ability to find new ways to be resilient in the wake of natural disasters?

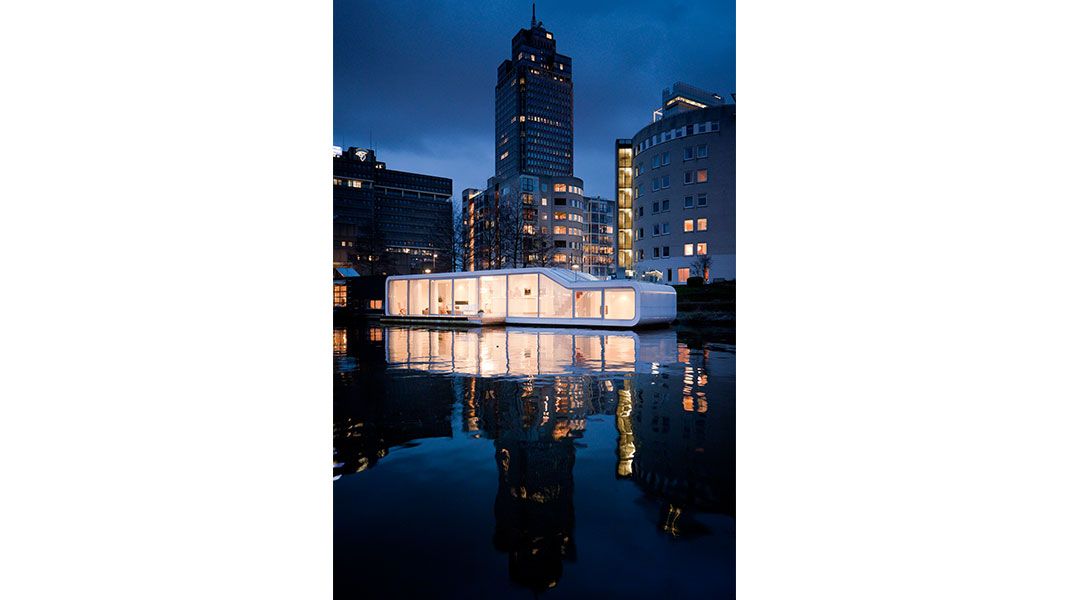

All of these matters are at the heart of a new photo exhibition at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles. Titled “Sink or Swim: Designing for a Sea Change,” the show features powerful images from the aftermath of catastrophe—a New Jersey roller coaster, for instance, relocated in the surf by Sandy—but it pays considerably more attention to the ingenuity of architectural responses to it.

“We humans have such a remarkable capacity for ingenuity,” said curator Frances Anderton, a respected architecture and design writer and the host of “DnA: Design and Architecture” on KCRW, the public radio station in Los Angeles. “I’ve seen that we can do the silliest things, and we can do the smartest things. We wanted to reflect the smart thinking.”

The exhibition covers a lot of ground, from floating schools in Bangladesh and Nigeria to a growing village of stilt houses in Benin in West Africa to a neighborhood in New Orleans’ Ninth Ward where homes have been rebuilt to be both more resilient and more sustainable, using 75 percent less energy than typical structures.

But “Sink or Swim” is not about photography of buildings. It consciously focuses on how human lives are changed by hurricanes, tsunamis and floods and on solutions for withstanding their fury in the future. For the most part, those whose work is featured are not architectural photographers, but photographers with a more journalistic or documentary bent, such as Stephen Wilkes, who first began capturing New Orleans’ devastation just months after Katrina hit, and Monica Nouwens, known more for producing candid images of people.

Anderton’s hope is that the exhibition, which runs through May 3, will show people what is possible in sustaining communities near unpredictable waters, but also increase awareness of the need to revive what she refers to as the “soft edges” of waterfronts—the marshes and wetlands that can serve as natural buffers between water and buildings.

“For the past 50 years, we built as though we could concretize ourselves out of any situation. But we built ourselves into weakening defenses,” she noted.

“Now let’s give a soft edge to this. Let’s create things that change in a positive way our relationship to water,” she said.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)