How Lego Patents Helped Build a Toy Empire, Brick by Brick

The Danish toy company invented its basic brick, then designed a toddler-friendly version, before adding mini figures to the mix

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/1f/8d1f7c92-2c7b-4051-bb98-56434b40450b/duplo-production.jpg)

In the continuing saga of Lucy Wyldstyle and Emmet Brickowski, Earth is overrun by rather large plastic bricks that lay waste to the planet. The invaders keep attacking and “Ar-mom-ageddon” is threatened unless peace is restored. What is Bricksburg to do?

That’s the premise of “The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part,” which premieres in theaters nationwide February 8. The very tongue-in-cheek animated film features an impressive lineup of voice actors, including Chris Pratt, Elizabeth Banks, Will Arnett, Nick Offerman, Will Ferrell and Maya Rudolph.

Of course, the real stars are the Lego bricks themselves. They are everywhere in the imaginary world created by brother and sister Finn and Bianca, who struggle with each other for toyland domination.

Lego Duplo, larger bricks designed for little hands, are the attacking force that wreak havoc on Bricksburg, which is constructed of the smaller Lego classic bricks. Lego figures are the inhabitants who must avoid the annihilation of “Ar-mom-ageddon” – what mom will do if Finn and Bianca don’t stop fighting.

This newest installment in the Lego movie franchise is all made possible by the enduring popularity of the interlocking plastic brick system that has captivated the imaginations of young and old alike for decades.

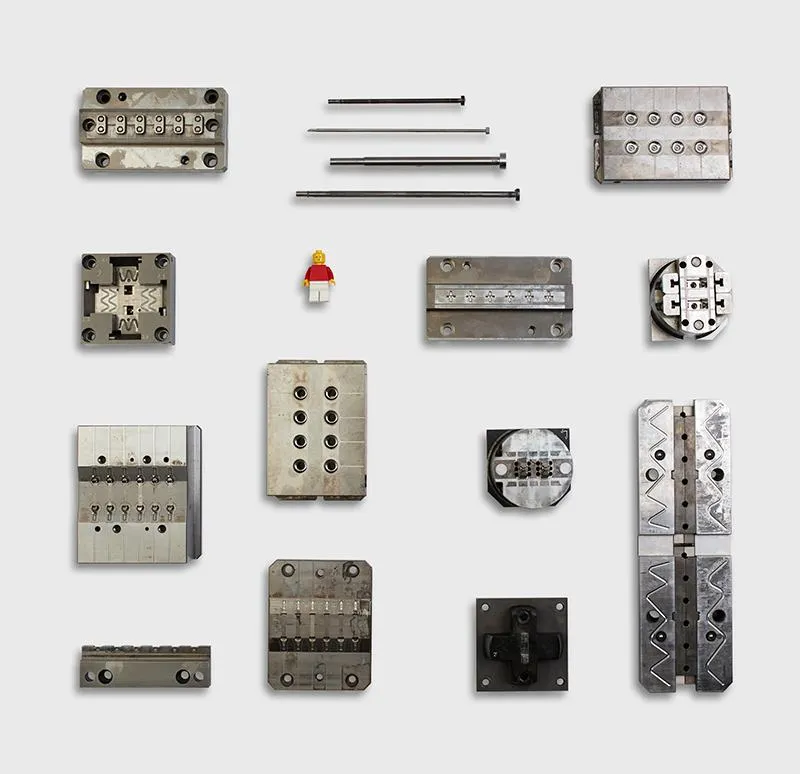

The interlocking toy system was the brainchild of Godtfred Kirk Christiansen, son of a Danish toymaker. His father Ole started the company in 1932 and named it Lego—a twist of the Danish words leg godt, meaning “play well.” Their first plastic bricks, modeled on an earlier British design, were not very popular until Godtfred hit upon the idea of actually inventing a system of compatible toys.

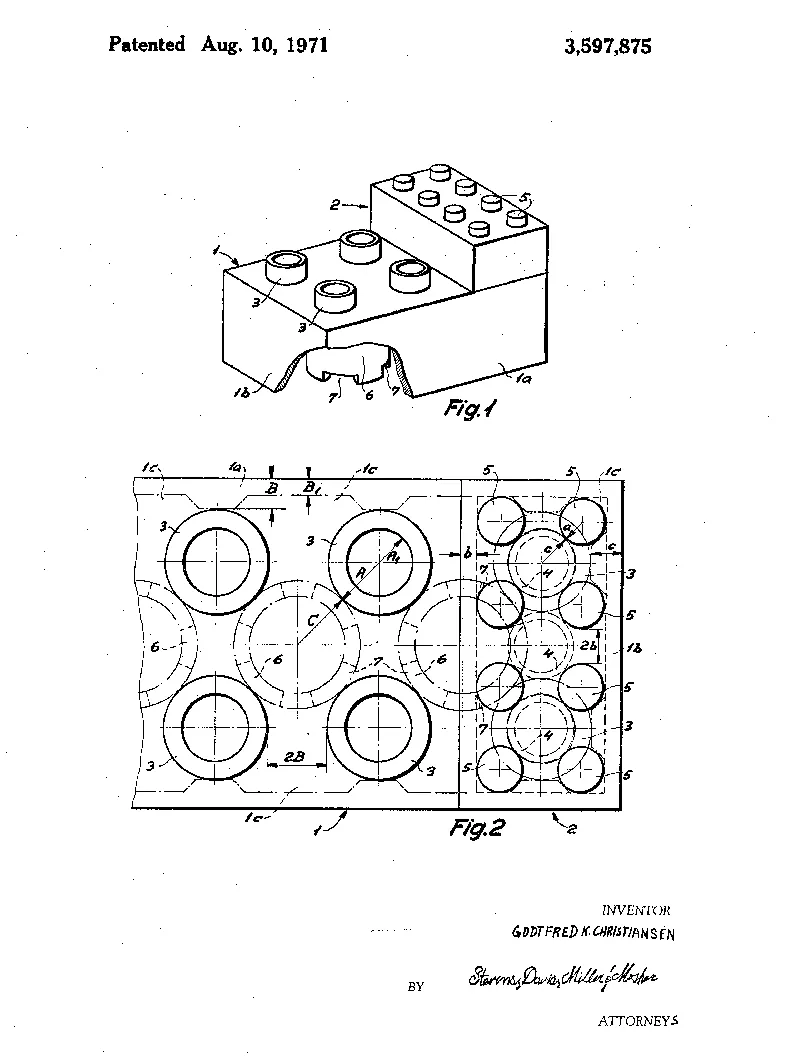

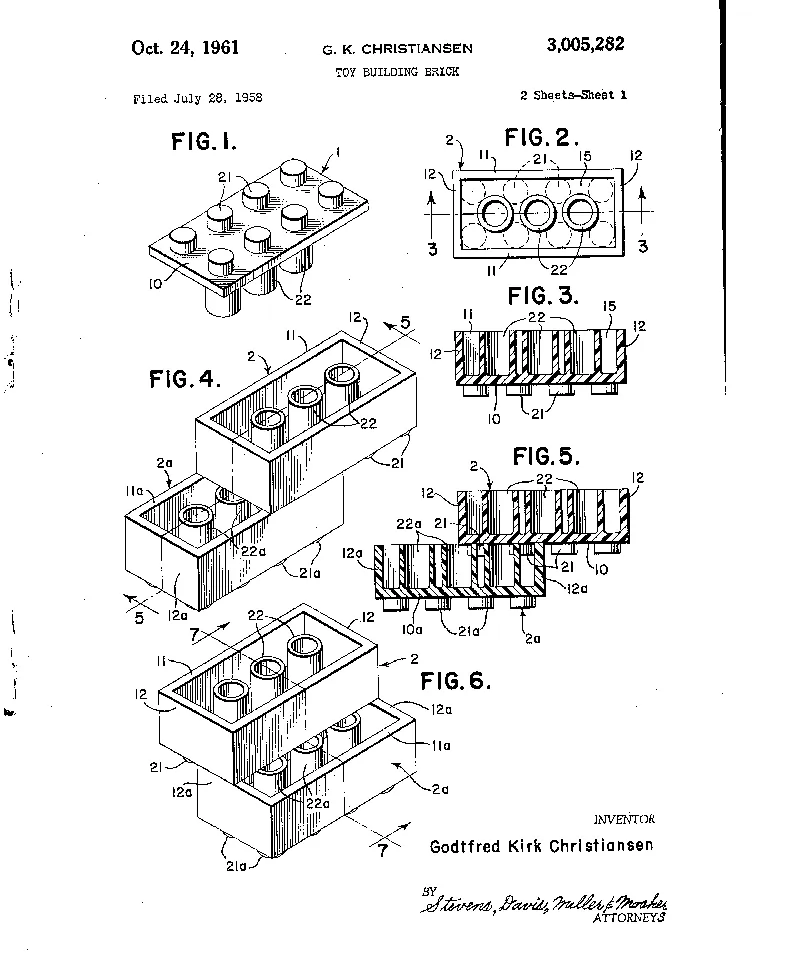

Christiansen first received a U.S. patent for a “toy building brick” in 1961. That original design of a rectangular plastic piece with eight “primary projections” (studs) on the top and three “secondary projections” (tubes) underneath is virtually unchanged in nearly six decades.

Those “projections” were crucial in allowing the pieces to lock together while unlocking an infinite combination of construction possibilities. Suddenly, children—and, yes, adults too—could unleash their imaginations in assembling Lego bricks in countless configurations.

“Before Lego, there really was no system of toys that worked together,” says Will Reed, a Lego expert who writes for The Brick Blogger. “The versatility of this system lets the user build just about anything they can dream of: a dinosaur, car, building, even something that only exists in the world of tomorrow.”

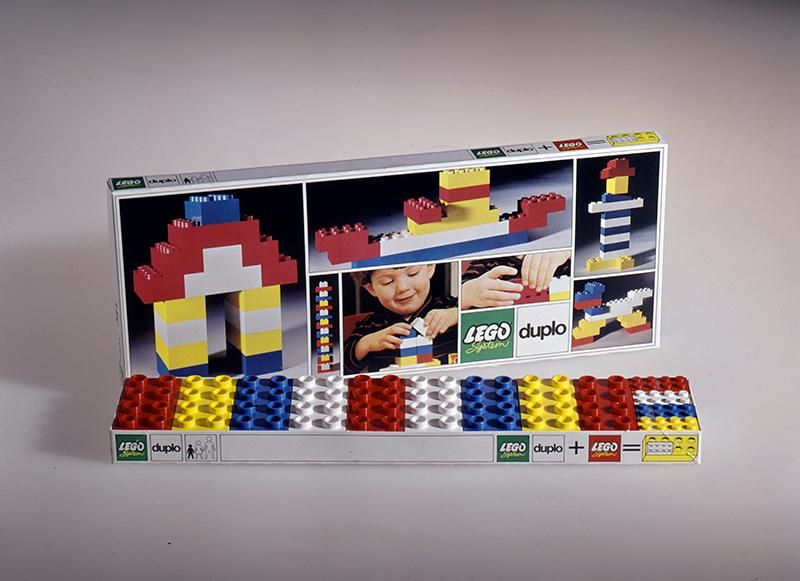

Intended to serve much younger consumers whose tinier hands were challenged by the smaller pieces, Duplo bricks were twice the size of the original parts, hence the Duplo name (for a short time, Lego also attempted to market Quatro bricks, which were four times as large). The key to success with this line extension, which debuted 50 years ago, was the fact the tubes on the original bricks plugged into the hollow studs on the top of the bigger bricks, providing a truly integrated system that Lego patented in 1971.

“Many builders of large-scale Lego models will use Duplo bricks for fill,” Reed says. “If you are working on, say, a mountain, you can use the large pieces on the inside. The pieces easily connect with the regular Lego bricks, so the design is seamless.”

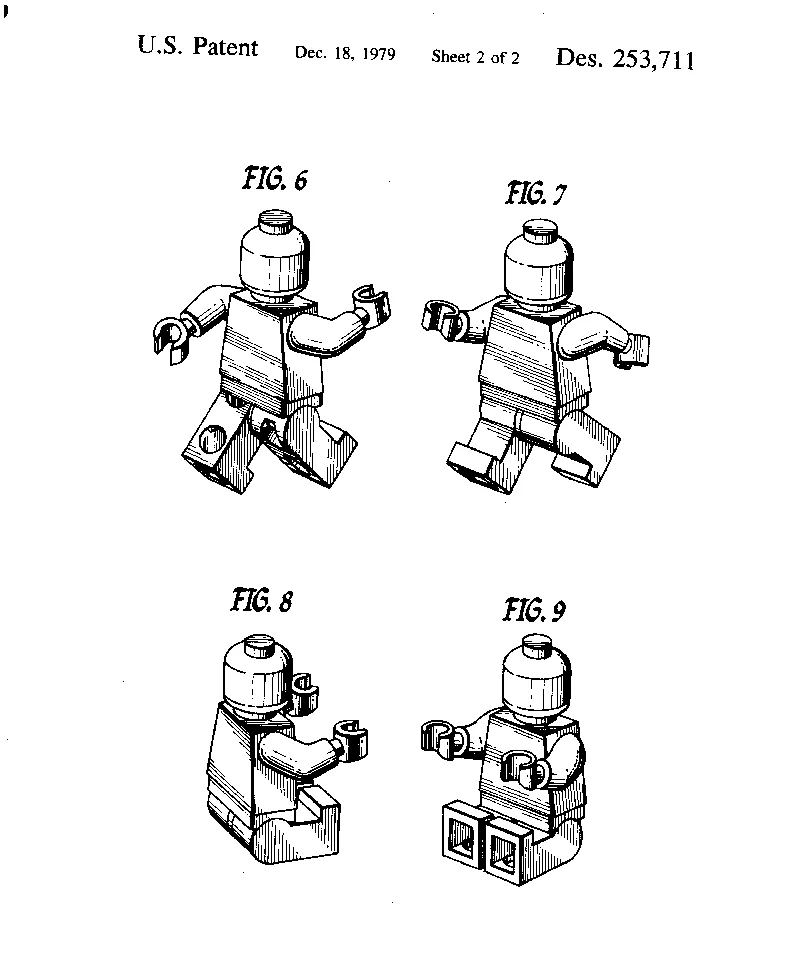

In 1979, Christiansen received a design patent for the Lego character—known simply as a “toy figure.” Complete with movable arms and legs, it suddenly introduced an entirely new dimension to the franchise. Now fans could include people to their creations, adding a human element to the three-dimensional fantasy worlds they fashioned from those colorful plastic pieces.

That pushed Lego into a whole new world of development. Faceless and following a basic human form at first, the toy figures soon acquired identities and professions so they could enhance the multitude of themed products that were being introduced. Now there were firemen with kits for fire engines and firehouses, policemen with squad cars, and so on.

Over time, the figure even acquired gender. At first, Lego introduced token characters—a female pirate in a pirate-themed set, for instance. Then, Lego realized they were missing out on a lucrative girls market, so, in 2012, the hotly debated “Lego Friends” kits launched with some stereotypically female settings. Lego would eventually introduce female characters as scientists, police and other historically male-dominated roles.

Of course, the human figure attracted the attention of Hollywood and led to the creation of those very successful Lego movies. Now the characters had distinct voices and quirky mannerisms—while using clever catchphrases—that helped bolster popularity and sales of licensed kits to coincide with movie releases.

“Lego is as relevant today as it was when it was first introduced,” Reed says. “The company has worked hard to expand the line and keep it current with consumers. Their efforts are aimed at making sure Lego brand toys will not become obsolete."