Can Young Botanists at a Magnet School Play a Vital Role in Protecting an Urban Ecosystem?

Miami’s BioTech, the country’s first ever botany-focused magnet high school, is teaching kids real-world plant science

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/63/3063b634-754e-4b83-9757-b54a755aefa7/biotech_students_prepare_solution_for_million_orchid_project.jpg)

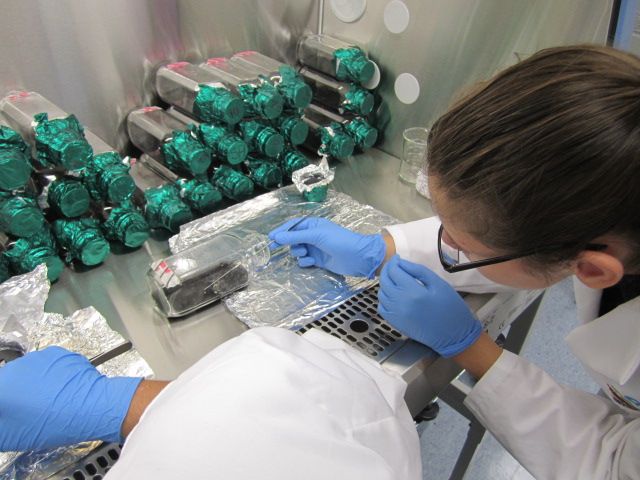

In the micropropagation lab at Miami’s BioTECH, high school freshman are carefully transplanting orchid seeds and taking tissue samples.

The students in the inaugural class at the magnet school, which focuses on conservation biology, are not dinking around with rudimentary science projects. The lab is filled with the kinds of machines you’d expect to find in a graduate level lab, and the students are working on a field study to reintroduce native orchids to south Florida. By their senior year, they’re expected to publish research in peer reviewed journals.

BioTECH, the first school of its kind, is a partnership between Miami Dade County School District, the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden and Zoo Miami. Both Fairchild and the Zoo had field trip programs for middle school students in the past, but they decided they wanted to raise the level, and give kids the opportunity to get involved in the actual science.

“We’d been talking to the school district for a while about botanically enriched curriculum,” says Carl Lewis, the director of Fairchild Garden. “We have very effectively popularized the field of botany here in Florida. We have many enthusiastic school children, and we were looking for the next step.”

The school district, which is generally supportive of magnet schools, backed the idea and applied for grant funding to build the facility. They annexed part of the existing Richmond middle school's property to build a full DNA lab with thermocyclers and a High-performance liquid chromatographher. “The initial idea was to do project based learning, but once we got our staff on board we twisted it into a research program,” says Daniel Mateo, the assistant principal.

This year, 122 9th graders from 33 middle schools across the county—and an area of 327 square miles—started school at BioTECH, after applying and being selected from a lottery of 250 students. They get a standard high school curriculum, but they also spend a couple of hours each day in the lab at the school, as well as at the two research institutions. As a freshman, their elective time goes to field biology and as sophomores they'll focus more on lab science. Mateo says he and the staff, which is comprised of teachers from the school district and scientists from zoo, Fairchild and nearby universities like University of Miami, hope to see the school top out at 800 students.

“The kids can take the project all the way from seed to plants out in the community,” Lewis says. “It’s not something you typically get in high school, or really anywhere else. Usually you’re working in a lab or a field, one or the other. Here kids can be crossing back and forth.” He says students have been really eager. The school has had to set up lab time on weekends, because they want to come in and check on their plants.

There are quite a few STEM-focused magnet schools across the country, and there are other schools that are affiliated with botanic gardens. The Brooklyn Academy of Science and the Environment brings its freshman to the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens once a week, for instance. But none of these other schools, Lewis says, are doing field biology research on the level of BioTech. By the time they graduate, students have to concieve of and complete their own research project, with the expectation, Mateo says, that these papers be published. They can also start to take concurrent college courses.

Nationally, high schools are increasingly test-focused, and in Florida, high schoolers need to pass reading and math tests to graduate. A science assessment isn't required, which means that it's easy to let more specific subjects, like botany, fall by the wayside. BioTECH is trying to give its students an understanding of traditional field science as well as biotechnology, so that they’ll be prepared for the future of the field. “Botanists will have to figure out how to feed a growing population and make plant communities more resilient to climate change,” he says. “We need to prepare these students for where botany is going to be in the future.”

That’s resonated across the field. When Lewis delivered a presentation about BioTECH at the Education Congress for Botanic Gardens in St. Louis in April, scientists from other institutions were already asking about how the school could route students into their programs after they graduated. A 2010 study from the Botanic Gardens Conservation International found that the number of undergraduates with botany degrees had dropped by half since the late 1980s, and half of the universities that had botany programs had eliminated them over that same time period.

It makes sense that the first magnet school dedicated to botany would be in Miami. Plant science has a big role in the climate, economy and the history of South Florida, from the orange groves to the orchid smuggling trade. “We have green plants 12 months a year, and we’re able to grow many plants from some of the most diverse places in the world,” Lewis says.

BioTech’s biggest endeavor this year is the Million Orchid Project, which started at Fairchild. The students are planting 1 million native orchids—eight different species, including the rare ghost orchid—across the city, trying to regenerate the struggling orchid population, which was decimated starting in the late 1800s by poaching and overeager orchid enthusiasts. It’s based on a successful project that took place in Singapore, where botanists planted orchids in high-density urban areas. “In their studies of survivorship, the survival rates in the city were equal to or greater than in their natural surroundings,” Lewis says. “Orchids don’t seem to care about what’s happening at ground level, as long as there’s a tree canopy, they can grow just fine.”

The project gives the students a chance to do lab and field work, and it also gets them out into the city, putting their knowledge into action. Lewis says Fairchild Garden has been working on the project since 2012, but the students are giving them a boost, especially in propagation. “When the BioTECH school opened, they built a lab just like ours, but bigger,” he says.

According to Mateo, one of the school's big goals is to tie the curriculum to real-world skills and to give the students a knowledge base that could serve them in the beginning of their careers. “The coolest part is seeing these kids do real science and then draw conclusions from the science they’re doing,” he says. “They’re 14 years old, and they’re putting it together.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)