Two Women, Their Lives Connected by American Slavery, Tackle Their Shared History

One descended from an enslaver, the other from the people he enslaved. Together, they traveled to the Deep South to learn their families’ pasts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/7d/757dd920-4bf2-495f-a50b-e45ae657fc09/thepast.jpg)

We were an odd couple, Karen and I, when we first arrived at the Montgomery County Archives in Alabama. These days, descendants of both slaves and slaveholders come to the archives seeking the truth about their past. Rarely do we arrive together.

Karen Orozco Gutierrez, of Davenport, Iowa, is the great-granddaughter of an enslaved man named Milton Howard, whose life she has long worked to document. As a girl, Karen heard stories about her great-grandfather, who told his children he was born in the 1850s to free people of color in Muscatine, Iowa, but that when he was a child he was kidnapped by slavers and taken with his family down the Mississippi River. His first enslaver was a planter in Alabama named Pickett.

Combing through records online, Karen established that Pickett had owned two cotton plantations, Cedar Grove and Forest Farm, both near Montgomery. But in all her searching of slave inventories, she couldn’t find anyone named Milton.

The man Karen believed was Milton’s enslaver was my great-great-grandfather on my father’s side. My father, Richard G. Banks, was born in Montgomery in 1912, but he left his roots for the itinerant life of a career Army officer. I attended 17 schools in five states and two countries, reinventing myself each time we moved. This was not an upbringing that encouraged looking to the past. I barely identified with the person I’d been the year before, let alone with distant ancestors.

Yet the evidence was there. From my father, I inherited an archive about our Alabama kin: wills bequeathing family oil portraits; yellowed newspaper clippings about antebellum homes-turned-museums; hand-drawn genealogical charts. I called this trove “The Pile” and quarantined it in a closet. If these bits and pieces told a story, I wasn’t ready to hear it. But recently, when a reinvigorated white supremacy seemed to be asserting itself, I knew it was time to take the Confederates out of the closet.

Researching A.J. Pickett online took me to AfriGeneas, a website that helps African Americans trace their enslaved ancestors—and to Karen. On the site’s message board, I discovered that members viewed descendants of slaveholders, like myself, as potential sources of information, trading tips on the best way to approach us.

Karen had posted a note seeking anyone who might have information about an Alabama man named Pickett on whose plantation she believed her great-grandfather had been enslaved. When I wrote identifying myself as Pickett’s kin, she responded: “I have been waiting for this day!”

That was July 12, 2018. Over the next several months, Karen and I corresponded every few days. She asked me to look through my papers for any mention of slaves, any bills of sale or probate records. “Really just anything.”

I was sorry to tell her I’d found nothing to help with her search. Karen took this news graciously, and we continued to correspond. She wrote to put me at ease: “You didn’t own slaves.”

No reckoning would be adequate, I knew—but looking away was no longer an option. I wrote to Karen that I was thinking of going to Montgomery to look at the Pickett family papers. She suggested we tackle them together. Karen was hoping to locate a document that would confirm A.J. Pickett as Milton’s slaveholder. She knew the odds were long; still, she told me, “I am looking to visit the area where Grandpa was a slave. I want to walk where he may have walked. It’s not enough to know things in general. I want to know the details.”

We met for the first time in the Charlotte, North Carolina, airport, awaiting the plane that would take us to Montgomery. I was nervous. I had signed on for what amounted to a weeklong blind date. Karen’s emails had been warm, but given what I represented to her, how would she really feel? Would it be awkward meeting face to face? What would we say?

Suddenly there she was—a tall, slender woman walking toward me across the lounge, dressed elegantly in tailored brown leather pants, a silk blouse and a black trilby hat. She wrapped me in a big hug. Karen seemed to sense my uneasiness, and if reassuring me was a burden, she shouldered it lightly. “It was providential that we connected,” she said later. “That was your doing.”

With a comfortable rapport, we set to work. We imagined the Montgomery of the 1840s—the days when shackled slaves were marched from a dock on the Alabama River up Commerce Street and into a nearby slave warehouse. They would have passed the townhouse, long since torn down, where my great-great-grandfather lived with his wife and nine children when he wasn’t at one of his plantations. The slave warehouse is now the headquarters of the Equal Justice Initiative, a racial justice organization founded by public interest lawyer Bryan Stevenson.

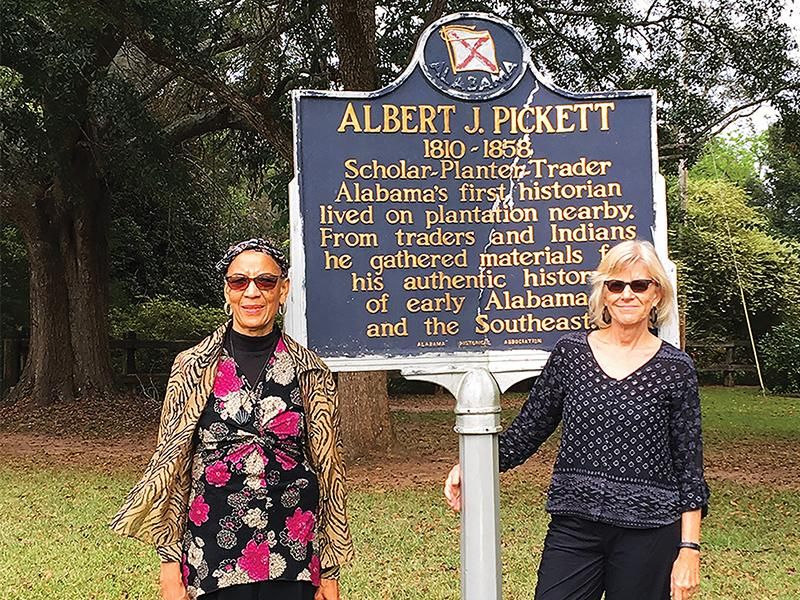

The morning after our arrival, Karen and I drove out to Autaugaville, site of Cedar Grove, to look around. Only woods remain where the plantation houses once stood. We took a picture of ourselves at a cracked historical site marker describing A.J. Pickett as a “Scholar-Planter-Trader.” From there, we headed to our main research site, the Montgomery County Archives, where property transactions were recorded. Housed in the basement of a brick building, the archives are overseen by Dallas Hanbury, an Alabaman with a PhD in public history.

To track my great-great-grandfather, Hanbury told us, we should start with the deed indexes, looking for transactions to which A.J. Pickett had been a party. Karen and I began turning the huge pages. After years of research, Karen was accomplished at deciphering 19th-century handwriting, and she read out the names and numbers of the deals. I scribbled a messy list of nearly 30 entries. This would be our starting point for tackling the deeds themselves.

A.J. Pickett was not just a planter but also a pioneering historian. I had inherited a musty first edition of his 1851 opus with the title stamped in gold: History of Alabama: And Incidentally of Georgia and Mississippi, from the Earliest Period. The book ends in 1819, when Alabama joined the United States.

On the subject of plantation slavery, Pickett’s book is mostly silent. For a long time, I’d imagined that my ancestor led a life of the mind, removed from the brutal realities of his time. I could not have been more wrong. Slavery was essential to his life and work. Indeed, A.J. Pickett believed that slavery, as practiced in the South, was both benign and necessary, and argued the point forcefully in his writing. The South’s steamy climate, he wrote, was “so destructive to the constitutions of the whites” that the land “could [n]ever have been successfully brought into cultivation without African labor.” For A.J. Pickett, abolitionists were enemies of progress. “These philanthropists would be willing to see our nation exterminated, and our throats cut, because we are pursuing a system of mild domestic slavery.”

Mild domestic slavery! A cruel oxymoron gave me a glimpse into my ancestor’s justification for owning human beings—Karen’s ancestors among them.

After the archives closed for the day, Karen and I adjourned to a restaurant for enchiladas. Her late husband, she told me, had been a veterinarian from Mexico. I learned she was Catholic and that she worked out three times a week, a discipline she continued while we were in Montgomery. She confessed that she’d held stereotypes about the Deep South. “Now I realize I probably could have driven here,” she said, “but I would have been afraid to stop and get gas along the way.”

Karen had arranged for us to tour the Figh-Pickett House the next morning, the sprawling mansion that A.J. bought as one of the family’s many residences. He didn’t live long enough to move in, dying in October 1858, at age 48, two weeks after the sale was final. His widow, Sarah, lived in the house for 36 years, running it as a boardinghouse during and after the Civil War. The building is now home to the Montgomery County Historical Society.

When Karen scheduled our tour, she’d mentioned to the director that I was a Pickett descendant and she the descendant of a Pickett slave.

“Are you two related?” he’d asked.

“Not that I know of,” Karen deadpanned.

The director of the historical society, a courtly man named James Fuller, took us up to the cupola where Sarah Pickett had hidden the family silver from Union soldiers. He lamented that almost none of the silver had ended up at Pickett House, save one silver platter; the rest had gone to a descendant in Ohio.

Not all of it, I was tempted to say. Not the two fluted serving spoons in my silverware drawer at home, one of them engraved “Eliza to Corinne Pickett.” I later told Karen about them, and we wondered whether Milton had ever polished them.

Fuller asked if I’d been to Montgomery before. His question brought back a sudden memory: I was 9, and my father had brought me to visit two aged cousins, a pair of sisters who shared a big house. What I recalled most vividly was their cats, which they’d trained to jump into a basket so they could be hauled to the second floor by a pulley. The sisters were A.J. Pickett’s granddaughters. One of them, Edna, was an enthusiastic family historian, and during our visit she gave my father many of the documents that ended up in The Pile. What stuck in my 9-year-old brain was the basket, and the image of the cats rising slowly in the air, as if in a storybook or a dream.

“Oh yes,” Fuller said. “That house was over on Lawrence Street. It isn’t there anymore, but we have the basket.”

Hearing this story later, a cousin of Karen’s noted that it illustrated the disparity between our situations. My ancestry was so clear that I could relate a childhood memory to a stranger and he could identify which ancestors I was talking about and where they’d lived, even down to the bric-a-brac they’d left behind. Karen, by contrast, had worked for years just to confirm the basic facts of her ancestor’s early life.

Back at the archives, Karen and I began our search by guessing which transactions seemed most likely to include the sale of Milton. Viewing the deeds on microfiche was tedious, and after a few hours I returned to the hotel. Karen stayed, even though it was near closing time.

I had barely set foot in my room when an email arrived with the subject line: “I found Milton!” The note continued, “I transcribed this in a hurry—it’s a first draft—but I was excited to get it to you! I just can’t believe it!”

In one of the deed books, Karen discovered an entry that revealed at a glance why, in all her research into plantation slave inventories, she had never found Milton’s name: He had been placed into a trust, a common practice in the antebellum South. On May 2, 1853, according to the trust certificate, 2-year-old Milton, three adults, five teenagers and seven other children were transferred from Pickett’s ownership into a trust for the benefit of his wife. These enslaved people, designated only by first name and age, now technically no longer belonged to anyone named Pickett, but rather to a trust overseen by a judge named Graham.

Conclusively linking her great-grandfather to his primary slaveholder was a triumph for Karen. There was more to learn about Milton’s early life, but after years of searching, she finally had a fixed point from which to navigate.

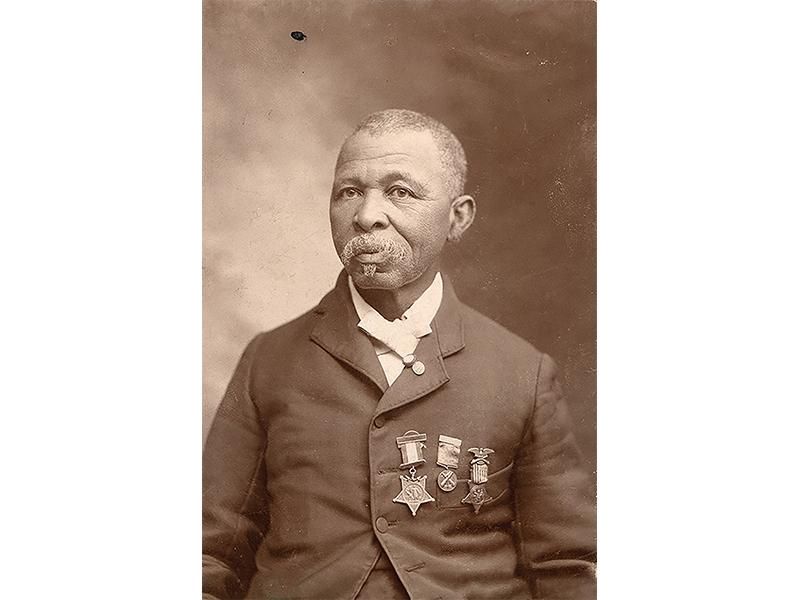

All Karen had known before coming to Montgomery was the latter part of Milton’s story: By the time he died in 1928, he’d become a celebrity in Davenport, Iowa. A front-page obituary paid tribute to him as a Union Army veteran who’d escaped an Alabama plantation and later worked at the Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois across the Mississippi from Davenport.

With her new discovery, Karen felt she had done a service to Milton—and to herself. “You want to know what happened to the people who came before you,” she told me over a celebratory dinner that night.

I realized this statement was truer of her than of me. Her ancestors had been robbed of their freedom and their history. Witnessing Karen’s struggle to find her forebears made it harder for me to look away from mine. Perhaps Karen sensed this, and her response was generous as usual. For our last morning in town, she suggested we visit Oakwood Cemetery, my Montgomery ancestors’ final resting place.

We arrived to find an enormous cemetery dotted with cedars, crape myrtles and oak trees thick with Spanish moss. Somewhere here were A.J. Pickett’s earthly remains, but we had no idea how to find him, so a young cemetery worker offered to lead us to the exact site. “Follow me,” he said, hopping into his red truck.

And there it was. The headstone was eroded, but we could make out the lettering: Albert James Pickett. Also listed was his daughter, my great-grandmother, Eliza Ward Pickett Banks.

As we stood before my great-great-grandfather’s grave, Karen told me she would like to say a prayer for him. “Hail Mary, full of Grace,” she began. An Episcopalian, A.J. Pickett had left the Baptists, by one account, because he liked dancing too much. I suspected this was the first time a “Hail Mary” had been said at his grave—not least by a descendant of someone he’d enslaved.

Karen’s generosity of spirit astonished me. I thought about the violent past that connected us and had brought us to this place. I thought of the deed conveying Milton into trust, signed 166 years ago by the man buried at our feet. I reminded Karen that she had just prayed for the person who enslaved her great-grandfather. “Yes, I know,” she said. “Everyone can be granted grace.”

The Germans have a word, Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung, which translates as “working off the past.” It was coined to describe the process by which Germans have striven to acknowledge and learn from their Nazi history. Only now, in the protests over the death of George Floyd in police custody, are there glimmers that something like this might be possible in the United States—a nationwide movement to confront and examine the devastating and persistent legacy of slavery.

Karen and I had both been searching for something on our journey to Montgomery. Against all odds, she found Milton. I learned that the stories of my slaveholding family had been there all along, waiting for me to become willing to know them. Such willingness comes gradually, slowly—until suddenly, in moments that illuminate the landscape like summer lightning, it’s no longer possible to look away.

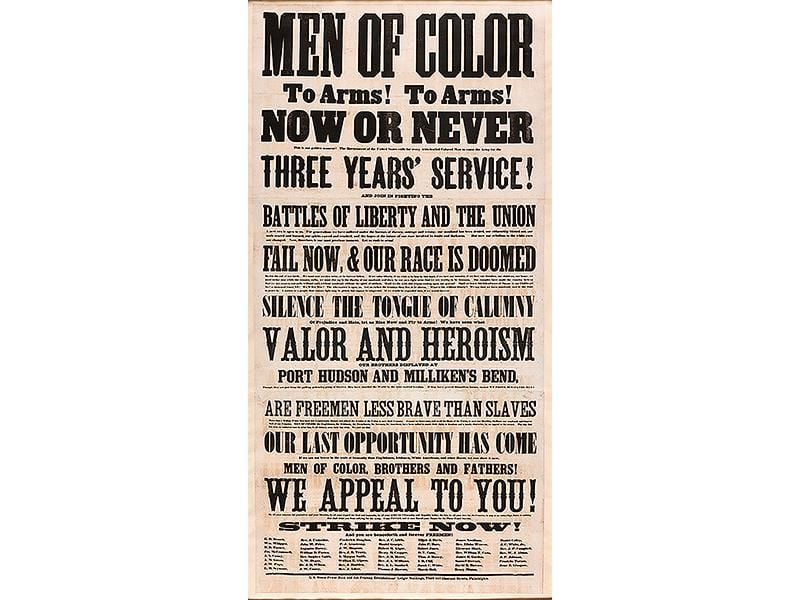

"Fail Now and Our Race Is Doomed"

Remembering the roughly 200,000 black Americans who fought for the Union —Courtney Sexton

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sexton_Remy.jpg)