Who Was the Marquis de Sade?

Even in the age of Fifty Shades of Grey, the 18th-century libertine is as shocking as ever

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/51/9a/519acaf7-c0fd-464b-b87f-b09b7fe26f62/feb15_g10_marquisdesade.jpg)

The Count de Sade, the modern descendant of the Marquis de Sade, whose rabid erotic works inspired the term sadism for sexual cruelty, resides in a sunny and strikingly decorated apartment on a quiet residential street on the Right Bank of Paris. After pressing a buzzer neatly labeled “H. de Sade,” I was greeted warmly at the door by Hugues himself, an avuncular 66-year-old with a coiffed shoulder-length mop of hair, wearing a florid Gallic ensemble of blue blazer, red-pinstriped shirt, yellow trousers and bright orange loafers. His elegant wife, Chantal, plied me with coffee and cake, as the count settled on the snow-white sofa, next to a table set out with copies of his ancestor’s novels—including the scabrous 120 Days of Sodom, scribbled by the marquis when he was imprisoned in the Bastille before the revolution. The count says he has never encountered any problems because of the once-reviled Sade name. “Au contraire, people are fascinated to learn that the Marquis de Sade was not a fictional figure.”

Enthusiasm in France for his notorious 18th-century ancestor is now such that the count has begun his own line of luxury goods, Maison de Sade. He started with Sade wine, from the family’s ancestral region of Provence, with the signature of the marquis on the label. He also offers scented candles and soon plans to add tapenade and meats. “It is quite natural,” Hugues explained. “The Marquis de Sade was a great gourmand. He adored fine wine, chocolate, quail, pâté, all the delicacies of Provence.” Hugues said he is now in discussions with Victoria’s Secret for a line of Sade lingerie. “We are in the early stages, but the signs are promising.”

Such marketing would have been unimaginable even a few years ago. The lurid works of Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade, who lived from 1740 to 1814 and died in a mental asylum, were banned in France until 1957, and the diabolical aura around his literary output has lifted only gradually. In fact, according to Hugues, his ancestor’s very existence was erased from the Sade family memory. Hugues’ parents had not even heard of him until the late 1940s, when the historian Gilbert Lely turned up on their doorstep at the Condé-en-Brie castle, in the Champagne region east of Paris, looking for documents relating to the author. “For five generations, the marquis’ name was taboo in our family,” Hugues marveled. “It was as if there was an omertà (conspiracy of silence) against him! The family no longer even used the title marquis.”

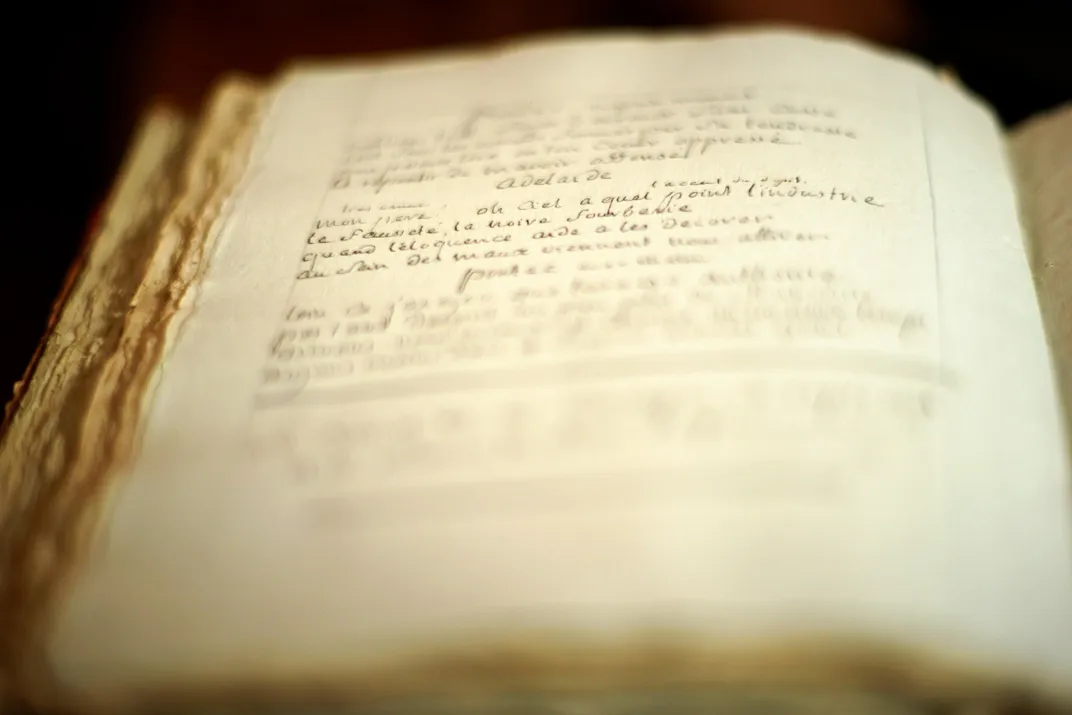

Intrigued by Lely’s tale, Hugues’ excited parents, then young newlyweds, began to explore the rambling Condé castle, and soon discovered that a wall had been bricked up in the attic. When they broke through, they found a jumble of dusty valises filled with documents hidden some time earlier by ashamed family members—the Marquis de Sade’s letters, papers, even shopping lists scrawled on scraps of parchment.

“The letters showed Sade the man, how he was a decent human being,” Hugues said. “How he wrote touching love letters to his wife, his two sons, his daughter.”

From that day on, the Sade family dedicated itself to vindicating the memory of its forgotten ancestor, mounting a crusade that coincided with the loosening of censorship in France in the 1950s. Sade’s work became widely available in the rebellious ’60s, and the door opened for the once-disgraced marquis to become France’s most decadent cultural hero, a frenzied aristocratic libertine who is now hailed by some as a literary genius and martyr for freedom.

The family’s embrace of their ancestor is such that Hugues named his eldest son, now 39, Donatien, a first in generations. “We’re proud of the marquis,” Hugues said. “And why not? Today, he is considered a great philosopher. His works are published by the most prestigious publishing house in France, Gallimard. There are conferences about him at the Sorbonne. He is the subject of university theses, and is studied by high-school students in the baccalauréat.”

As we spoke, Hugues pulled down from his bookshelf an array of distinctive heirlooms passed down from the attic trove—the marquis’ church prayer book, original plays (with notes in the margins), his annotated copy of Petrarch (the 14th-century Italian poet’s great love, Laura, may have been a member of the ancient Sade clan)—as well as an enormous rare volume of erotic Salvador Dali drawings inspired by Sade’s novels. As a parting gesture, he produced a bottle of Sade red wine named after one of the marquis’ most famous heroines, Justine, who suffers bloodcurdling abuse as she travels the world. Sade’s novel Justine: The Misfortunes of Virtue, goes far beyond Voltaire’s Candide in its desire to show humanity’s inherently evil nature.

“Some of his writing is too extreme even for me,” Hugues said. “It is work of total delusion.”

***

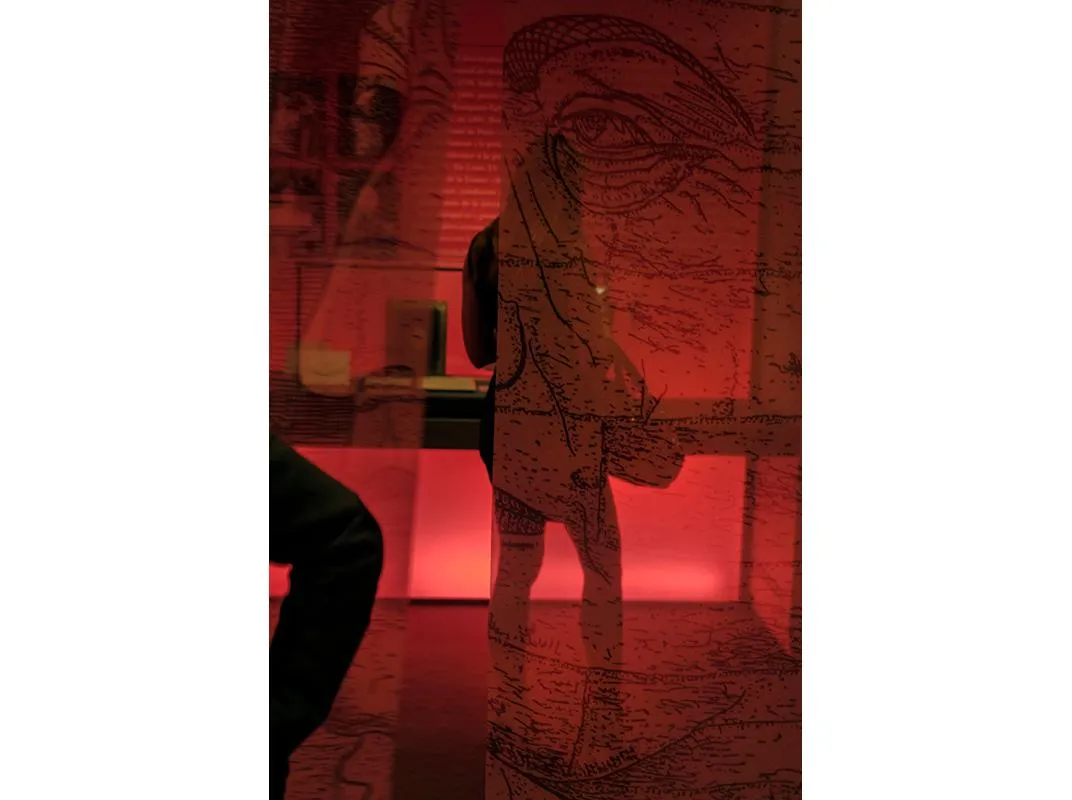

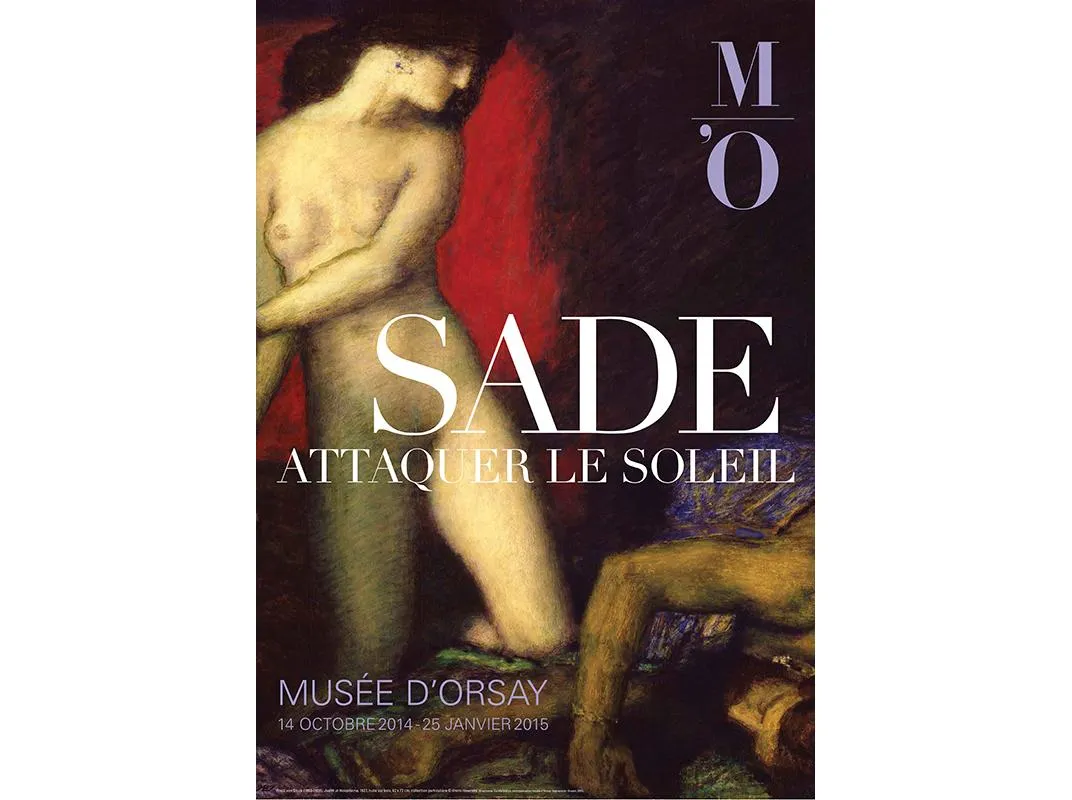

The Marquis de Sade’s rehabilitation was all but complete last month. Paris marked the 200th anniversary of the author’s death, which occurred on December 2, 1814. The “secret manuscript” of The 120 Days of Sodom was returned to France last April with fanfare. The Musée d’Orsay has an exhibition on Sade’s influence on the visual arts (“Sade. Attacking the Sun”). New editions of his writings are being issued by the prestigious publisher Gallimard’s Pléiade imprint, the ultimate literary consecration in France. There are new biographies, Sade bicentennial blogs, Facebook pages and newsletters. In French-speaking Geneva, the Bodmer Foundation is exhibiting Sade’s letters until April (“Sade, an Atheist in Love”). Not all the commentary is flattering, to be sure. “Sade’s work is important, but I don’t accept his deification,” says Ovidie, a French actress, filmmaker and writer who uses a stage name. “His books were written to justify his monstrous behavior, all the sexual crimes he committed.”

While Sade was alive, censors shuddered at his accounts of rape, incest and pedophilia, as well as his vitriolic atheism, and thousands of his books were destroyed. He remained all but unknown in the 19th century beyond a tiny band of cognoscenti, including Flaubert and Baudelaire, who found underground copies of his books or gained access to the forbidden Enfer, or Hell, section of the National Library in Paris.

In the early 1900s, the critic and poet Apollinaire wrote the first unabashed essays in defense of Sade, and by the 1920s his cause was taken up by the Surrealists, including Man Ray, André Breton and Dali. They were attracted to Sade’s demands for complete sexual freedom and political liberty, as well as the hallucinogenic nature of his imagination. They dubbed him the “Divine Marquis,” after the provocative Italian Renaissance author the “Divine” Pietro Aretino. By the mid-20th century, opinion-makers such as Jean-Paul Sartre were championing his banned works, and cheap pirated editions found their way to the famously open-minded French public.

To his admirers, Sade’s influence runs deep. His novels were among the first to explore the dark, hidden impulses of human nature, prefiguring Freud’s idea of the subconscious by a century. He presented homosexuality as no more or less “normal” than heterosexuality, anticipating the modern gay movement long before Oscar Wilde. And his demand to remove all “civilized restraints” on behavior imposed by the state, the church and moribund tradition inspired iconoclastic modern writers from Louis-Ferdinand Céline to Henry Miller in their quests for individual freedom.

“Sade’s influence has been enormous in every sphere of Modernist art,” said Laurence des Cars, one of the curators of the exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay. “His aim was to destroy every illusion surrounding human sexuality, be it historical, moral or religious, which inspired artists to look at the body in a new way.” In visual art, she cites Delacroix, Watteau, Degas, Ingres and Picasso (“Look at the way Picasso plays with the body, inside and out, showing it dominated by the gaze of the viewer”). In cinema, Sade inspired a string of works, including Dali and Luis Buñuel’s classic L’Âge d’Or and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, which transfers The 120 Days of Sodom to the grim setting of Italy in the early 1940s.

“Alfred Hitchcock was also influenced,” des Cars adds. “Once you start looking, you see Sade’s presence throughout popular culture.”

She is conscious that the exhibition will push the boundaries for a fine arts institution, with warnings for parents about its shocking graphic content. But the bicentennial also provides the perfect opportunity to peel away the myths that surround Sade, des Cars says. “Everyone has an idea of sadism,” she says, referring to the term coined by the psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing in 1888. “But Sade himself remains a figure of fantasy. Everybody knows him, yet nobody knows him.”

***

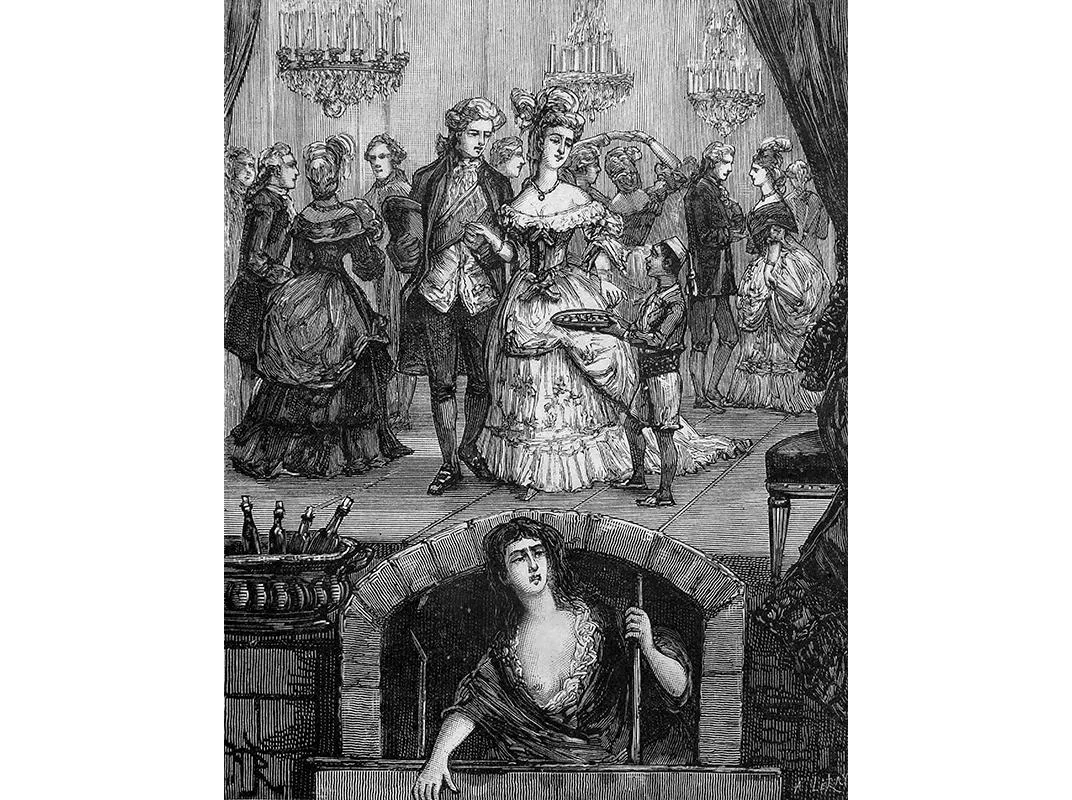

On the Right Bank of the Seine in Paris is Le Marais, a neighborhood that the Marquis de Sade would recognize from his youth, a maze of winding alleyways once frequented by Racine and Molière. Here, it’s easy to imagine Sade as a vain young nobleman, in powdered wig and exquisitely tailored silk costume, weaving in his horse-drawn carriage through streets teeming with fish vendors and hawkers, en route to the theater he loved. The only known portrait of the marquis is a profile he sat for at age 19. His delicate, feminine features belie his feral charisma. But he was already displaying a lack of self-control that made his behavior extreme even by the standards of debauched French aristocrats. And his sordid antics with prostitutes and lovers of both sexes only seemed to escalate after his marriage at age 23 to Pélagie, the wealthy, plain daughter of the upper-middle-class Montreuil family.

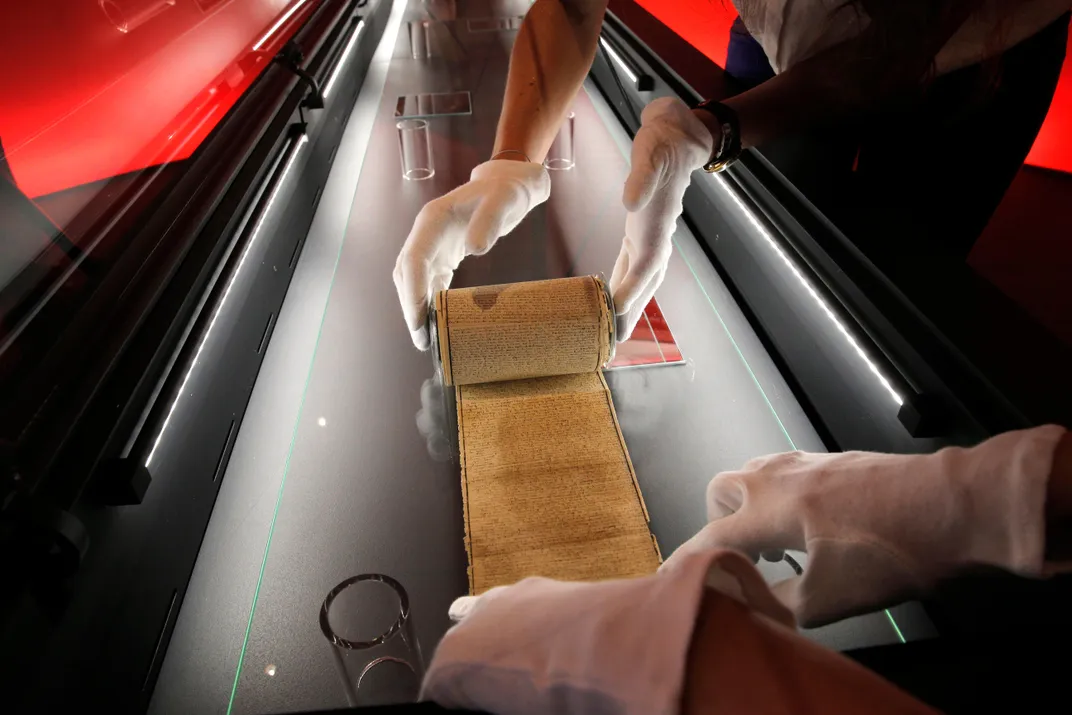

Today, the pre-revolutionary world is in fashion in France, in part because of its libertine spirit, as I witnessed at a soiree at the Palace of Versailles. The venerable Antiquarians’ Society was hosting a lavish dinner for its biennale, which attracts leading antiques dealers and scholars. After passing through the village of Versailles (where the young Sade kept a pied-à-terre for trysts), I strolled through the Hall of Mirrors while the setting sun lit the chandeliers. As we sipped Champagne in the gardens, conversation turned to the rescue of Sade’s “secret manuscript,” The 120 Days of Sodom, now regarded as part of the national patrimony. “We are all thrilled that 120 Days is back in France,” one elderly dealer said. The manuscript, itself a bizarre objet d’art, written on a tightly coiled 39-foot-long scroll, had been the subject of legal wrangles for decades that were closely watched by European dealers. When I confessed my desire to examine it, he shrugged. “It’s in vaults more secure than the Bastille. But I am friends with the owner. I will put you in touch.”

The next day, I found myself in a setting scarcely less grand than the Palace of Versailles itself. The offices of the rare books company Aristophil include a museum of letters and manuscripts at the Hôtel de la Salle, a 17th-century Parisian mansion whose ornate halls have been restored this year to their original brilliance. I was led through endless silent chambers to the last gilded room, where the director, Gérard Lhéritier, presided at his vast desk.

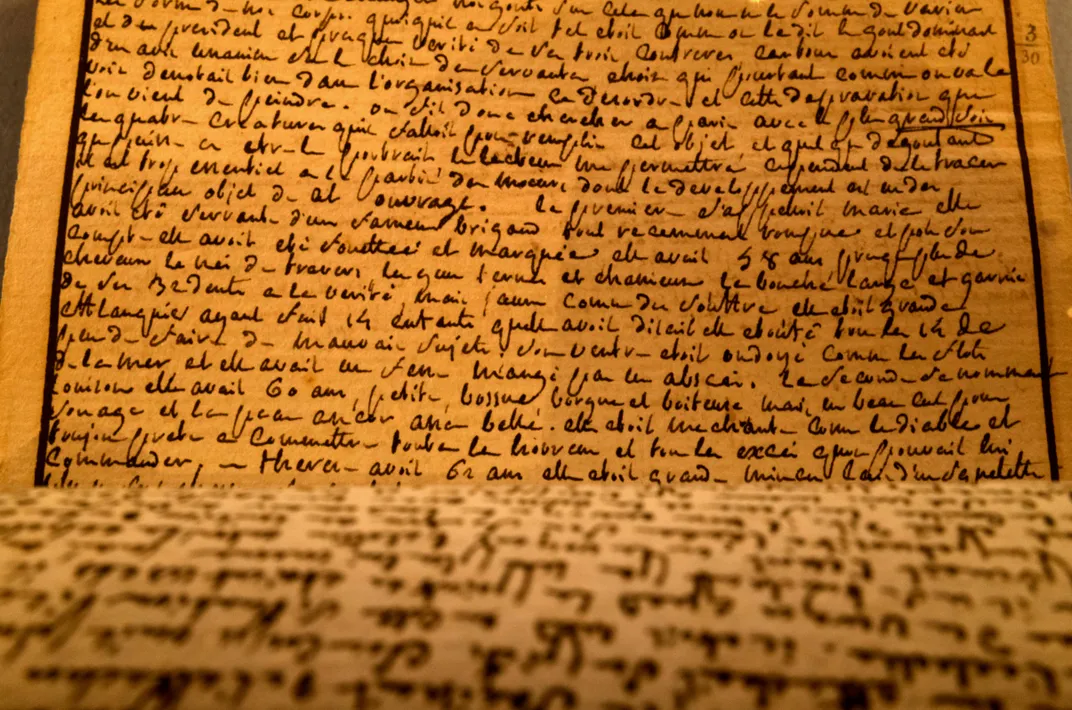

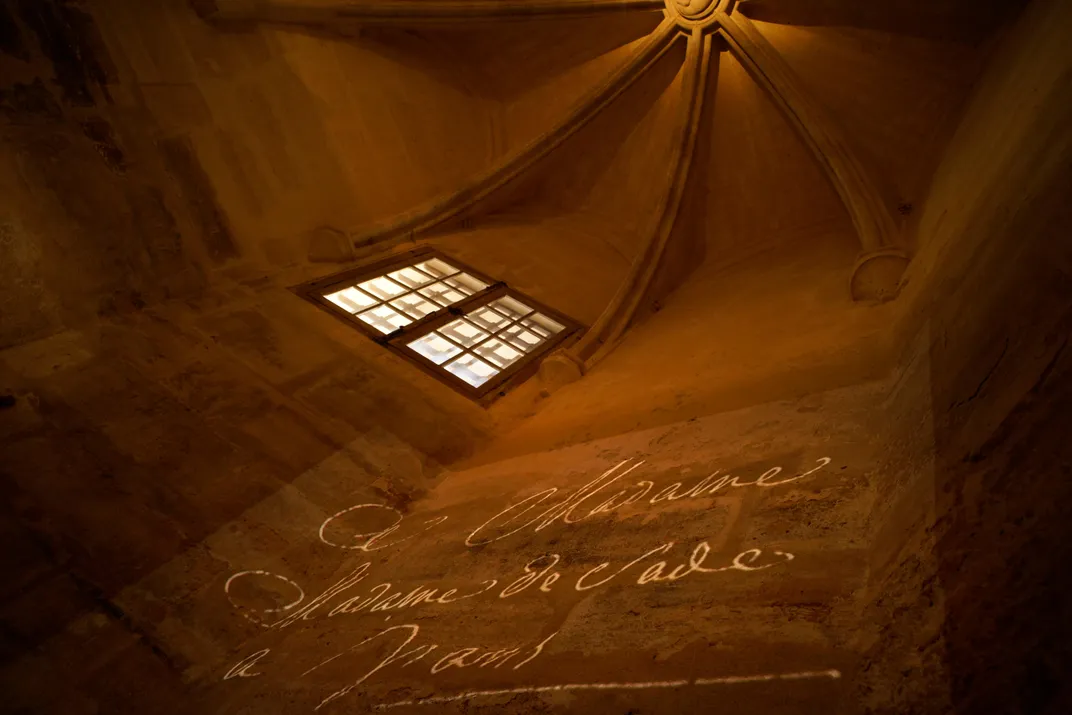

As Lhéritier spoke, an attendant in white cotton gloves entered with a leather-bound box, inside of which the scroll was sitting on velvet. It is surely one of history’s most peculiar manuscripts, written by Sade on small pieces of paper smuggled into the Bastille in 1785 and glued together into a single long scroll, which, tightly wound, could be hidden in the wall of his prison cell. The marquis must have had excellent eyesight. As the attendant unraveled the opus, she handed me a magnifying glass, since the scrawled text is so minuscule it can be read only with assistance. “I am not an admirer of Sade’s writing in general,” Lhéritier said. “I prefer calmer literature. But the history of the scroll fascinated me. It’s a mythic artifact.”

120 Days was first lost in 1789, when the revolutionary mob stormed the Bastille. A few nights earlier, Sade had been suddenly removed from his cell, “naked as a worm,” and transferred to another prison. (He had been using an improvised megaphone to harangue the crowds, declaring that the inmates were being slaughtered, and begging for rescue, a provocation that did not endear him to the warden.) “I have shed tears of blood,” Sade wrote, and he died believing that the manuscript was destroyed when the Bastille was sacked. Miraculously, he was wrong. Two days before the mob attacked, an eagle-eyed citizen found the roll hidden in the wall—historians know nothing more about him than his name, Arnoux de Saint-Maximin—and for unknown reasons, decided to save it. The manuscript fell into the possession of a wealthy French family, and finally re-emerged in 1904 in Berlin, where a German collector published the first edition of 180 copies, making it an instant legend among the world’s connoisseurs of erotica.

A wing of the Sade family returned 120 Days to France in 1929. But then, in 1982, a descendant lent the scroll to a bookseller, who absconded with it and sold it to a Swiss collector. Two legal cases were started to return the stolen text: A court in France put it on the Interpol list of stolen artifacts, but a Swiss court ruled in favor of the Geneva collector, saying he had bought it “in good faith.” Requests by the French National Library to purchase it were rebuffed.

All seemed lost until 2011, when word went out that the son of the Swiss owner (who had died in 1992) was finally willing to sell. “I was in ecstasy when I heard the news,” recalled Lhéritier. “I jumped up in the air like a goat!” For three years, Lhéritier struggled to strike a deal that included the French former owners, whose approval was needed to remove the item from Interpol’s list. He finally cut a deal for €7 million ($9.6 million) split between the families, and flew back in triumph last March from Geneva with the scroll in a private jet. The price tag put the novel among the most valuable manuscripts on earth, in the company of Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex, the Magna Carta and John James Audubon’s complete The Birds of America, to name a few. (In November, French authorities began investigating Lhéritier and his lavishly funded company for possibly running a Ponzi scheme, a charge he denies.)

The hushed respect for the scroll offers a contrast to the ferocious nature of its contents, which lives up to Sade’s boast that he had produced “the most impure tale that has ever been written.” Glancing over the text, I saw snippets of Sade’s most maniacal imagery—feverish orgies, monstrous depredations repeated ad nauseam, rants against religion and authority of all kinds. The novel relates the saga of four depraved aristocrats who imprison 28 teenage victims of both sexes, torturing and finally murdering their prey. It is the very ur-text of sadism, which most critics agree is unreadable. The Sade biographer Francine du Plessix Gray called it “borderline psychotic.” Even Lhéritier admits he has trouble. “Sade was crazed,” he said. “The book is an apology for every atrocity. If you read six pages, you have to put it down, you can’t take it.”

In pre-revolutionary France, aristocratic males routinely evaded criminal charges because of their social status and wealth. Today, Sade’s real-life depravity is simply horrifying. The first scandal occurred in 1763, when the 23-year-old marquis locked a young prostitute in a room and began stomping on a crucifix and screaming blasphemies, then demanding that she whip him with a cat-o’-nine-tails. Five years later, in the village of Arcueil, he whipped a woman and (legal documents suggest) dripped hot wax on her back; she fled and contacted the police, but was paid off to drop charges.

Sade decamped to Provence in the South of France, where he owned a lavishly renovated château in the village of Lacoste. Today, the region, called the Luberon, is beloved by acolytes of the writer Peter Mayle for its renovated farmhouses, plump olives and rolling green hills, but in the 18th century, it was a raw and remote backwater requiring more than a week of hard travel from Paris, the perfect refuge from royal officers of the law. Sade acted the benevolent feudal overlord with his wife Pélagie (with whom he seemed to have a mutually loving relationship, calling her “celestial kitten” and “fresh pork of my thoughts”), and playing games with his two young sons and daughter. His staff included a lecherous valet (and sometime lover), Latour, and a maid named Gothon, who, Sade said, had “the sweetest ass ever to leave Switzerland.” It was here that Sade committed one of his most disturbing crimes, in 1774: Five young females and one male were trapped in the château for six weeks of depredations, orchestrated in theatrical fashion by Sade under the indulgent eyes of his wife.

The Château Sade was sacked in 1789 during the revolution, but in the 20th century, its ruins became a destination for literary pilgrims such as Henri Cartier-Bresson (who photographed it) and Lawrence Durrell (who reportedly penned the steamier sections of his Alexandria Quartet in a local café). As interest in Sade grew, Lacoste drew more attention. In 2001, the derelict castle was purchased by the French fashion icon Pierre Cardin, who renovated the interior and erected a shiny bronze statue of the marquis, with a cage around his head to signify his years of imprisonment. Cardin even hosts a theater festival there every summer in honor of Sade, who had a passion for the stage.

Driving to Lacoste, I spotted the château perched on a stone crag in the distance, like the ideal summer home for Bela Lugosi. Slippery cobbled streets led to the castle portals, where—as in any good horror movie—a visitor bangs the iron door knocker to enter. Cardin’s valet took me to meet the fashion designer, now 92 and in robust health, sporting a navy blue blazer and crisp shirt, his tousled white hair over signature frames. “I’ve always felt great sympathy for Sade,” he said. “He was persecuted for his writings, and suffered enormously. He did exactly what he wanted to do, just like me.”

I crept down a stone stairwell in the dark to the basement, and used a flashlight to illuminate the outline of the cell where Sade kept his victims trapped for part of their six-week ordeal in 1774.

After the incident, villagers began to weary of Sade’s depraved behavior. (“I’m being taken for a werewolf in these parts,” he complained.) And Sade had already made a misstep that would cost him dearly: He had offended his mother-in-law. Madame de Montreuil once doted on the charming Sade, but in 1772 he ran off to Italy with his wife’s younger sister. Sade’s wife apparently forgave him, but the wrath of his mother-in-law was undying. It was she who helped the authorities hunt Sade down. Police finally broke into the château one night in the summer of 1777, and took Sade, then 37, “tied and muffled” to Paris. He would spend 29 of his remaining years in prison or an insane asylum, under three radically different French regimes, those of King Louis XVI, the revolution and Napoleon Bonaparte.

The dreaded Bastille was demolished in 1789 (the site is a busy traffic circle today). But Vincennes, the prison where Sade spent seven years, is an imposing tourist attraction, where guides show off his cell. The aristocratic Sade was permitted his library of 600 books, armchairs and a desk, while his wife was free to bring him the latest fashions and his favorite foods. (With characteristic phrasing, he once demanded a chocolate cake that was as black “as the devil’s ass is blackened by smoke.” No wonder the Surrealists loved him.) Sade had always fancied himself a writer, but until his imprisonment he had not produced anything but a few staid drafts of plays and a tedious travelogue about Italy. Now in confinement, surging with rage and frustration, he began to produce vast amounts of material, filling thousands of manuscript pages and completing drafts with lightning speed—in part to make money, in part to embarrass his nemesis, his mother-in-law.

***

To prepare for his recent biography Sade: Angel of the Shadows, the Parisian author Gonzague Saint Bris took the writer’s entire oeuvre to a remote Caribbean island, where he read every grisly word. “I was not happy,” he told me. “The iguanas were all looking at me, thinking ‘Poor Gonzague!’” Saint Bris almost decided that Sade was simply too appalling a character to spend time with. “But as I read more, my reaction went from revulsion to compassion. Sade languished for a third of his life in prison without standing trial. It’s a terrible fate.”

Like many Sade experts I met, Saint Bris was decidedly eccentric. When he opened the door to his Left Bank mansion for our mid-afternoon meeting, I found him in pink pajamas emblazoned with the family crest, his hair flailing like Beethoven’s. The 67-year-old author’s palatial abode is a literary cabinet of curiosities, jammed with thrilling arcana such as original letters by Victor Hugo and the tricycle of Jean Cocteau. The stairways were covered with photos of the younger Saint Bris, a dashing figure hanging out with Mick Jagger, Michael Jackson and Carla Bruni.

Saint Bris had his own take on Sade. He said he first realized the marquis’ influence as a 20-year-old during the May 1968 student riots in Paris. “I looked at all the placards, reading ‘It is Forbidden to Forbid,’ and ‘Do Whatever You Desire.’ I suddenly understood that our revolutionary phrases were actually from Sade. I began to see a phantom wearing his powdered wig standing on the barricades beside me!”

The key to Sade’s erotic work, he argued, is the author’s poignant longing to never be forgotten, which only became more intense as the years in the Bastille dragged on into his late 40s. “Sade wanted to become a famous writer. He deliberately chose his subject—sex and perversion, every possible horror—so he could become immortal. Today, Sade is a household name all around the world, even in Japan and Russia. Rock groups use it. And he made sure that nothing written about sex would surpass him. Fifty Shades of Grey is a nursery book compared to Sade!”

Many feminists have a more critical view. The American critic Andrea Dworkin, for example, denounced Sade’s writing in 1981 as virulently misogynistic. For another perspective, I sought out Ovidie, the filmmaker and feminist writer, who first gained attention a decade ago starring in pornographic films and is still an activist for sexual freedom. “His philosophy is very powerful,” she said when we met in a Paris café. “But he’s no Nietzsche! There was once a time to fight for Sade and against the censorship laws. But that time has passed. We must still be able to criticize him.” Ovidie argued that Sade’s life should not be separated from his writings. “He is seen as a misunderstood author, who suffered in prison for his heroic stand. But he was not jailed at first because of his writings....The ones who defend Sade are all men. Voilà!”

Yet some French intellectual women defend Sade too. “I do not accept a misogynist reading of his writing,” says Sade exhibit curator Laurence des Cars, citing the study of her fellow curator and biographer Annie Le Brun, Sade: A Sudden Abyss. “His novel Juliette is one of Europe’s first pro-women books, where women dominate entirely.” (In it, the vicious heroine perpetrates sexual atrocities on hapless males, from peasants to the pope.) “Even in 120 Days of Sodom, men and women are on the same level.”

***

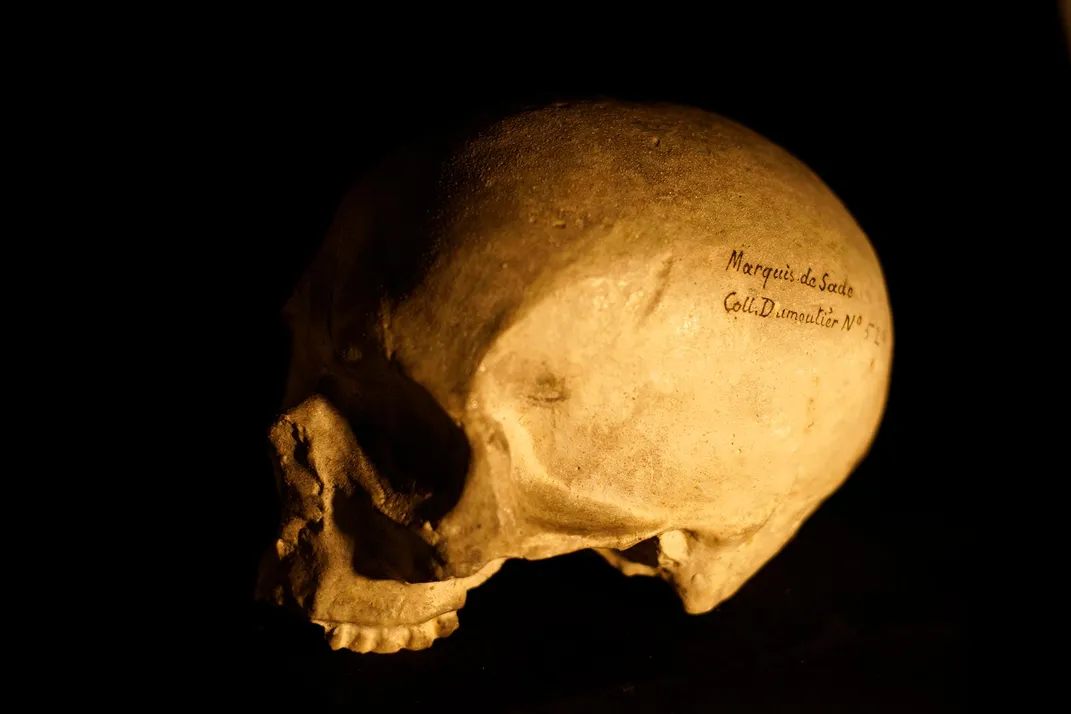

In 1801, after several years of freedom, Sade was arrested yet again on the orders of Napoleon, who found Juliette the “abominable” work of a “depraved imagination,” and soon ended up in Charenton, an insane asylum. Here, in his 60s, Sade gained a new level of notoriety by staging his plays with fellow inmates as actors, a surreal final act in Sade’s life that inspired the modern films Marat/Sade and Quills. He died unrepentant at age 74, and was given a religious service, against his last wishes. Soon after, a young doctor sympathetic to Sade, L.J. Ramon, exhumed the corpse and removed the cranium, intending to make phrenological studies of this troubled creative spirit. Ramon lent the skull to a German colleague, who then disappeared with it. The relic was lost, but legend has long held that Ramon made a cast of the skull before it left Paris, and the plaster copy of the cranium survives today.

From Sade experts I learned that the 1814 skull mold was given to a French collector, a certain Charles-Albert Demoustier, who in the 1830s donated it to the Museum of Phrenology. It passed through various institutions before arriving a century later in France’s anthropology museum, the Museum of Man. Officials there at first denied that the skull was still in their collection, but when I contacted the curator, Philippe Mennecier, he invited me to the museum’s storage rooms, where over 18,000 historical craniums are preserved.

“Ours is not the biggest skull collection in the world, but it’s the most diverse,” said Mennecier, a gaunt figure whose somber undertaker mien belied his excitement in his work. We walked through neon-lit chambers filled with skeletons and death masks (“Here is Robespierre...here is Napoleon...here are 19th-century criminals, look, you can see the guillotine marks on their necks”) before he creaked open a metal wall cabinet.

From a cardboard box, Mennecier produced a skull cast, marked with an antique inscription “Marquis de Sade, Coll. Demoustier No. 529,” and presented it proudly.

“Can I hold it?” I asked.

“Bien sûr!”

It was a giddy moment, weighing the 200-year-old replica skull of the writer I had spent so much time with. Mennecier then opened the leather-bound records of the collector Demoustier, who studied the shape of the cranium in the 1830s to report on its “lunatic” aspects. (Phrenologists believed that the shape of a skull revealed traits such as criminality, artistic genius, saintliness and insanity.) Sade was “a licentious man, like Nero,” he had deduced, who “liked to make his debauchery bloody. Men with similar brain organizations will go so far as to kill the object of their lust in a bloody rage.” A more affectionate—if equally fanciful—study of the skull was made by Ramon, who had befriended Sade before he died. Ramon found the cranium to reveal “no ferocity” or “aggressive drives,” and “no excess in erotic impulses.” They were suitably misguided blurs of Sade’s life and writings—as fanciful as the pseudoscience of phrenology itself, which was discredited by the mid-20th century.

For his part, Count Hugues de Sade has borrowed the plaster cast and hired an artist to cast replica skulls in bronze. He is now selling them as souvenirs for the bicentennial of his ancestor’s death, in his Maison de Sade line. “I offer them directly for €2500 ($3,100),” he said, “but in boutiques they will cost up to €4,500 ($5,700).”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)