Weather Control as a Cold War Weapon

In the 1950s, some U.S. scientists warned that, without immediate action, the Soviet Union would control the earth’s thermometers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201112050240191954-May-28-Colliers-470x251.jpg)

On November 13, 1946 pilot Curtis Talbot, working for the General Electric Research Laboratory, climbed to an altitude of 14,000 feet about 30 miles east of Schenectady, New York. Talbot, along with scientist Dr. Vincent J. Schaefer, released three pounds of dry ice (frozen carbon dioxide) into the clouds. As they turned south, Dr. Schaefer noted, “I looked toward the rear and was thrilled to see long streamers of snow falling from the base of the cloud through which we had just passed. I shouted to Curt to swing around, and as we did so we passed through a mass of glistening snow crystals! Needless to say, we were quite excited.” They had created the world’s first human-made snowstorm.

After the experiments of G.E.’s Research Laboratory, there was a feeling that humanity might finally be able to control one of the greatest variables of life on earth. And, as Cold War tensions heightened, weather control was seen by the United States as a potential weapon that could be even more devastating than nuclear warfare.

In August of 1953 the United States formed the President’s Advisory Committee on Weather Control. Its stated purpose was to determine the effectiveness of weather modification procedures and the extent to which the government should engage in such activities. Methods that were envisioned by both American and Soviet scientists—and openly discussed in the media during the mid-1950s— included using colored pigments on the polar ice caps to melt them and unleash devastating floods, releasing large quantities of dust into the stratosphere creating precipitation on demand, and even building a dam fitted with thousands of nuclear powered pumps across the Bering Straits. This dam, envisioned by a Russian engineer named Arkady Borisovich Markin would redirect the waters of the Pacific Ocean, which would theoretically raise temperatures in cities like New York and London. Markin’s stated purpose was to “relieve the severe cold of the northern hemisphere” but American scientists worried about such weather control as a means to cause flooding.

The December 11, 1950 Charleston Daily Mail (Charleston, WV) ran a short article quoting Dr. Irving Langmuir, who had worked with Dr. Vincent J. Schaefer during those early experiments conducted for the G.E. Research Laboratory:

“Rainmaking” or weather control can be as powerful a war weapon as the atom bomb, a Nobel prize winning physicist said today.

Dr. Irving Langmuir, pioneer in “rainmaking,” said the government should seize on the phenomenon of weather control as it did on atomic energy when Albert Einstein told the late President Roosevelt in 1939 of the potential power of an atom-splitting weapon.

“In the amount of energy liberated, the effect of 30 milligrams of silver iodide under optimum conditions equals that of one atomic bomb,” Langmuir said.

In 1953 Captain Howard T. Orville was chairman of the President’s Advisory Committee on Weather Control. Captain Orville was quoted widely in American newspapers and popular magazines about how the United States might use this control of the skies to its advantage. The May 28, 1954 cover of Collier’s magazine showed a man quite literally changing the seasons by a system of levers and push buttons. As the article noted, in an age of atomic weapons and supersonic flight, anything seemed possible for the latter half of the 20th century. The cover story was written by Captain Orville.

A weather station in southeast Texas spots a threatening cloud formation moving toward Waco on its radar screen; the shape of the cloud indicates a tornado may be building up. An urgent warning is sent to Weather Control Headquarters. Back comes an order for aircraft to dissipate the cloud. And less than an hour after the incipient tornado was first sighted, the aircraft radios back: Mission accomplished. The storm was broken up; there was no loss of life, no property damage.

This hypothetical destruction of a tornado in its infancy may sound fantastic today, but it could well become a reality within 40 years. In this age of the H-bomb and supersonic flight, it is quite possible that science will find ways not only to dissipate incipient tornadoes and hurricanes, but to influence all our weather to a degree that staggers the imagination.

Indeed, if investigation of weather control receives the public support and funds for research which its importance merits, we may be able eventually to make weather almost to order.

An Associated Press article by science reporter Frank Carey, which ran in the July 6, 1954 edition of Minnesota’s Brainerd Daily Dispatch, sought to explain why weather control would offer a unique strategic advantage to the United States:

It may someday be possible to cause torrents of rain over Russia by seeding clouds moving toward the Soviet Union.

Or it may be possible — if an opposite effect is desired — to cause destructive droughts which dry up food crops by “overseeding” those same clouds.

And fortunately for the United States, Russia could do little to retaliate because most weather moves from west to east.

Dr. Edward Teller, the “father of the H-bomb” testified in 1958 in front of the Senate Military Preparedness Subcommittee that he was “more confident of getting to the moon than changing the weather, but the latter is a possibility. I would not be surprised if accomplished it in five years or failed to do it in the next 50.” In a January 1, 1958, article in the Pasadena Star-News Captain Orville warned that “if an unfriendly nation solves the problem of weather control and gets into the position to control the large-scale weather patterns before we can, the results could be even more disastrous than nuclear warfare.”

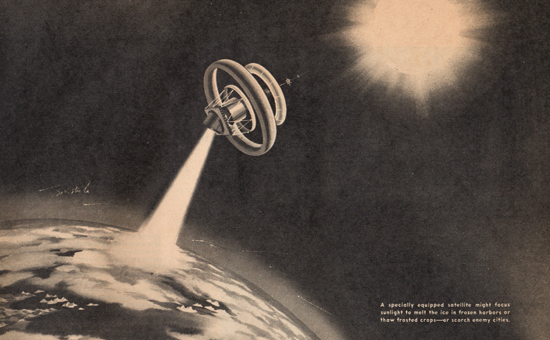

May 25, 1958 The American Weekly (illustration by Jo Kotula)

The May 25, 1958, issue of The American Weekly ran an article by Frances Leighton using information from Captain Howard T. Orville. The article, in no uncertain terms, described a race to see who would control the earth’s thermometers. The illustration that ran with the piece pictured an ominous looking satellite which could “focus sunlight to melt the ice in frozen harbors or thaw frosted crops — or scorch enemy cities.”

Behind the scenes, while statesmen argue policies and engineers build space satellites, other men are working day and night. They are quiet men, so little known to the public that the magnitude of their job, when you first hear of it, staggers the imagination. Their object is to control the weather and change the face of the world.

Some of these men are Americans. Others are Russians. The first skirmishes of an undeclared cold war between them already have been fought. Unless a peace is achieved the war’s end will determine whether Russia or the United States rules the earth’s thermometers.

Efforts to control the weather, however, would find skeptics in the U.S. National Research Council, which published a 1964 report:

We conclude that the initiation of large-scale operational weather modification programs would be premature. Many fundamental problems must be answered first….We believe that the patient investigation of atmospheric processes coupled with an exploration of the technical applications may eventually lead to useful weather modification, but we emphasize that the time-scale required for success may be measured in decades.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)