The Woman Who Took on the Tycoon

John D. Rockefeller Sr. epitomized Gilded Age capitalism. Ida Tarbell was one of the few willing to hold him accountable

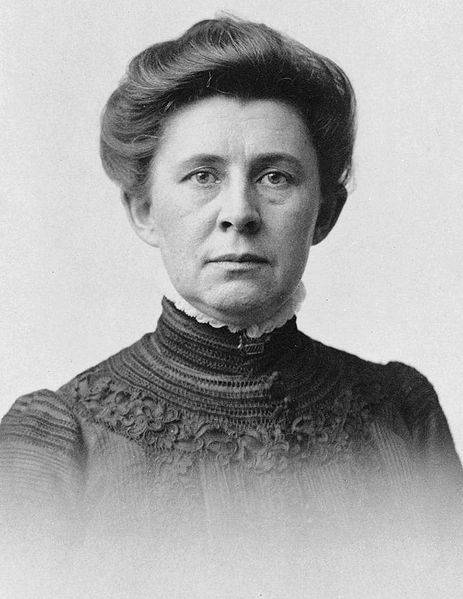

Ida M. Tarbell, c. 1904. Photo: Wikipedia

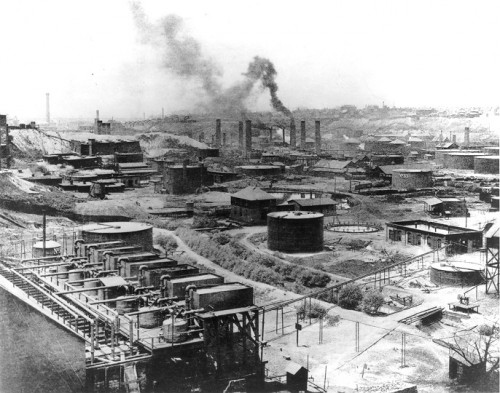

At the age of 14, Ida Tarbell witnessed the Cleveland Massacre, in which dozens of small oil producers in Ohio and Western Pennsylvania, including her father, were faced with a daunting choice that seemed to come out of nowhere: sell their businesses to the shrewd, confident 32 year-old John D. Rockefeller, Sr. and his newly incorporated Standard Oil Company, or attempt to compete and face ruin. She didn’t understand it at the time, not all of it, anyway, but she would never forget the wretched effects of “the oil war” of 1872, which enabled Rockefeller to leave Cleveland owning 85 percent of the city’s oil refineries.

Tarbell was, in effect, a young woman betrayed, not by a straying lover but by Standard Oil’s secret deals with the major railroads—a collusive scheme that allowed the company to crush not only her father’s business, but all of its competitors. Almost 30 years later, Tarbell would redefine investigative journalism with a 19-part series in McClure’s magazine, a masterpiece of journalism and an unrelenting indictment that brought down one of history’s greatest tycoons and effectively broke up Standard Oil’s monopoly. By dint of what she termed “steady, painstaking work,” Tarbell unearthed damaging internal documents, supported by interviews with employees, lawyers and—with the help of Mark Twain—candid conversations with Standard Oil’s most powerful senior executive at the time, Henry H. Rogers, which sealed the company’s fate.

She became one of the most influential muckrakers of the Gilded Age, helping to usher in that age of political, economic and industrial reform known as the Progressive Era. “They had never played fair,” Tarbell wrote of Standard Oil, “and that ruined their greatness for me.”

Ida Minerva Tarbell was born in 1857, in a log cabin in Hatch Hollow, in Western Pennsylvania’s oil region. Her father, Frank Tarbell, spent years building oil storage tanks but began to prosper once he switched to oil production and refining. “There was ease such as we had never known; luxuries we had never heard of,” she later wrote. Her town of Titusville and surrounding areas in the Oil Creek Valley “had been developed into an organized industry which was now believed to have a splendid future. Then suddenly this gay, prosperous town received a blow between the eyes.”

That blow came in the form of the South Improvement Company, a corporation established in 1871 and widely viewed as an effort by Rockefeller and Standard Oil in Ohio to control the oil and gas industries in the region. In a secret alliance with Rockefeller, the three major railroads that ran through Cleveland—the Pennsylvania, the Erie and the New York Central—agreed to raise their shipping fees while paying “rebates” and “drawbacks” to him.

Word of the South Improvement Company’s scheme leaked to newspapers, and independent oilmen in the region were outraged. “A wonderful row followed,” Tarbell wrote. “There were nightly anti-monopoly meetings, violent speeches, processions; trains of oil cars loaded for members of the offending corporation were raided, the oil run on the ground, their buyers turned out of the oil exchanges.”

Tarbell recalled her father coming home grim-faced, his good humor gone and his contempt directed no longer at the South Improvement Company but at a “new name, that of the Standard Oil company.” Franklin Tarbell and the other small oil refiners pleaded with state and federal officials to crack down on the business practices that were destined to ruin them, and by April of 1872 the Pennsylvania legislature repealed the South Improvement Company’s charter before a single transaction was made. But the damage had already been done. In just six weeks, the threat of an impending alliance allowed Rockefeller to buy 22 of his 26 competitors in Cleveland. “Take Standard Oil Stock,” Rockefeller told them, “and your family will never know want.” Most who accepted the buyouts did indeed become rich. Franklin Tarbell resisted and continued to produce independently, but struggled to earn a decent living. His daughter wrote that she was devastated by the “hate, suspicion and fear that engulfed the community” after the Standard Oil ruckus. Franklin Tarbell’s partner, “ruined by the complex situation,” killed himself, and Tarbell was forced to mortgage the family home to meet his company’s debts.

Rockefeller denied any conspiracy at the time, but years later, he admitted in an interview that “rebates and drawbacks were a common practice for years preceding and following this history. So much of the clamor against rebates and drawbacks came from people who knew nothing about business. Who can buy beef the cheaper—the housewife for her family, the steward for a club or hotel, or the quartermaster or commissary for an army? Who is entitled to better rebates from a railroad, those who give it for transportation 5,000 barrels a day, or those who give 500 barrels—or 50 barrels?”

Presumably, with Rockefeller’s plan uncovered in Cleveland, his efforts to corner the market would be stopped. But in fact, Rockefeller had already accomplished what he had set out to do. As his biographer Ron Chernow wrote, “Once he had a monopoly over the Cleveland refineries, he then marched on and did the same thing in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York and the other refining centers. So that was really the major turning point in his career, and it was really one of the most shameful episodes in his career.”

Still a teenager, Ida Tarbell was deeply impressed by Rockefeller’s machinations. “There was born in me a hatred of privilege, privilege of any sort,” she later wrote. “It was all pretty hazy, to be sure, but it still was well, at 15, to have one definite plan based on things seen and heard, ready for a future platform of social and economic justice if I should ever awake to my need of one.”

At age 19, she went to Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania. But after studying biology, Tarbell came to realize that she preferred writing. She took an editing job for a teaching publication and eventually worked her way up to managing editor before moving to Paris in 1890 to write. It was there that she met Samuel McClure, who offered her a position at McClure’s magazine. There, Tarbell wrote a long and well-received series on Napoleon Bonaparte, which led to an immensely popular 20-part series on Abraham Lincoln. It doubled the magazine’s circulation, made her a leading authority on the early life of the former president, and landed her a book deal.

In 1900, nearly three decades after the Cleveland Massacre, Tarbell set her sights on what would become “The History of the Standard Oil Company,” a 19-part series (and book) that, as one writer described, “fed the antitrust frenzy by verifying what many had suspected for years: the pattern of deceit, secrecy and unregulated concentration of power that characterized Gilded Age business practice with its ‘commercial Machiavellianism.’ ”

Ironically, Tarbell began her research by interviewing one of her father’s former fellow independents back in Pennsylvania—Henry H. Rogers. After the Cleveland Massacre, Rogers spent 25 years working alongside Rockefeller, building Standard Oil into one of the first and largest multinational corporations in the world. Rogers, it seems, may have been under the impression, after the McClure’s series on Lincoln, that Tarbell was writing a flattering piece on him; he reached out to her through his good friend Mark Twain. Meeting her in his home, Rogers was remarkably candid in some regards, even going to far as to provide her with internal documents and explaining the use of drawbacks in Standard Oil’s history.

Tarbell recalled that Rogers also arranged for her to interview another of Rockefeller’s partners, Henry Flagler, who refused to give specifics about the origins of the South Improvement Company. Instead, she sat “listening to the story of how the Lord had prospered him,” she wrote. “I was never happier to leave a room, but I was no happier than Mr. Flagler was to have me go.”

Franklin Tarbell warned Ida that Rockefeller and Standard Oil were capable of crushing her, just as they’d crushed her home town of Titusville. But his daughter was relentless. As the articles began to appear in McClure’s in 1902, Rogers continued to speak with Tarbell, much to her surprise. And after he went on record defending the efficiency of current Standard Oil business practices, “his face went white with rage” to find that Tarbell had uncovered documents that showed the company was still colluding with the railroads to snuff out its competition.

“Where did you get that stuff?” Rogers said angrily, pointing to the magazine. Tarbell informed him that his claims of “legitimate competition” were false. “You know this bookkeeping record is true,” she told him.

Tarbell never considered herself a writer of talent. “I was not a writer, and I knew it,” she said. But she believed her diligent research and commitment (she spent years examining hundreds of thousands of documents across the country, revealing strong-arm tactics, espionage and collusion) “ought to count for something. And perhaps I could learn to write.”

In The History of the Standard Oil Company, she managed to combine a thorough understanding of the inner workings of Rockefeller’s trust and his interest in the oil business, with simple, dramatic and elegant prose. While avoiding a condemnation of capitalism itself and acknowledging Rockefeller’s brilliance, she did not hesitate to criticize the man for stooping to unethical business practices in pursuit of his many conquests:

It takes time to crush men who are pursuing legitimate trade. But one of Mr. Rockefeller’s most impressive characteristics is patience. There never was a more patient man, or one who could dare more while he waited. The folly of hurrying, the folly of discouragement, for one who would succeed, went hand in hand. Everything must be ready before he acted, but while you wait you must prepare, must think, work. “You must put in, if you would take out.” His instinct for the money opportunity in things was amazing, his perception of the value of seizing this or that particular invention, plant, market, was unerring. He was like a general who, besieging a city surrounded by fortified hills, views from a balloon the whole great field, and sees how, this point taken, that must fall; this hill reached, that fort is commanded. And nothing was too small: the corner grocery in Browntown, the humble refining still on Oil Creek, the shortest private pipe line. Nothing, for little things grow.

Ida Tarbell concluded her series with a two-part character study of Rockefeller, where she described him as a “living mummy,” adding, “our national life is on every side distinctly poorer, uglier, meaner, for the kind of influence he exercises.” Public fury over the exposé is credited with the eventual breakup of Standard Oil, which came after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1911 that the company was violating the Sherman Antitrust Act. Tarbell ultimately forced Americans to consider that the nation’s best-known tycoon was using nefarious tactics to crush legitimate competitors, driving honest men from business. Ultimately, Standard Oil was broken into “baby Standards,” which include ExxonMobil and Chevron today. Rockefeller, a great philanthropist, was deeply stung by Tarbell’s investigation. He referred to her as “that poisonous woman,” but told advisers not to comment on the series or any of the allegations. “Not a word,” Rockefeller told them. “Not a word about that misguided woman.”

Almost 40 years after the Cleveland Massacre cast a pall over Titusville, Ida Tarbell, in her own way, was able to hold the conglomerate accountable. She died in Connecticut in 1944, at the age of 86. New York University placed her book, The History of the Standard Oil Company, at No. 5 on a list of the top 100 works of 20th-century American journalism.

Sources

Books: Ida M. Tarbell, All in the Day’s Work, Macmillan, 1939. Ida M. Tarbell, The History of the Standard Oil Company, The Macmillan Company, 1904. Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., Random House, 1998. Steve Weinbert, Taking on the Trust: The Epic Battle of Ida Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller, W.W. Norton & Company, 2008. Clarice Stasz, The Rockefeller Women: Dynasty of Piety, Privacy, and Service, iUniverse, 2000.

Articles: “The Rockefellers,” American Experience, PBS.org, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/rockefellers/sfeature/sf_7.html “The Lessons of Ida Tarbell, by Steve Weinberg, the Alicia Patterson Foundation, 1997, http://aliciapatterson.org/stories/lessons-ida-tarbell “Ida Tarbell and the Standard Oil Company: Her Attack on the Standard Oil Company and the Influence it had Throughout Society,” by Lee Hee Yoon, http://hylee223.wordpress.com/2011/03/21/research-paper-ida-tarbell-and-the-standard-oil-company/

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)