The Last of the Cornish Packmen

An encounter on a lonely road in the furthest reaches of the English West Country sheds light on the dying days of a once-ubiquitous profession

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cornish-packmen-elis-pedlar.jpg)

![]()

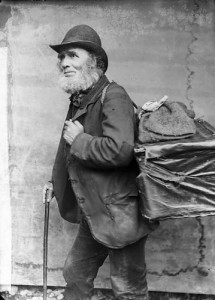

Elis the pedlar, a Welsh packman working the villages around Llanfair in about 1885. John Thomas Collection, National Library of Wales

Before the coming of the railways, and the buses, and the motor car, when it was not uncommon for isolated farms to be a day’s walk from the nearest shops, the closest many people got to a department store was when a wandering peddler came to call.

Wheeled transport was still expensive then, and most rural roads remained unmade, so the great majority of these traveling salesmen carried their goods on their backs. Their packs usually weighed about a hundredweight (100 pounds, or about 50 kilos—not much less than their owners), and they concealed a treasure trove of bits and pieces, everything from household goods to horsehair wigs, all neatly arranged in drawers. Since the customers were practically all female, the best-sellers were almost always beauty products; readers of Anne of Green Gables may recall that she procured the dye that colored her hair green from just such a peddler.

Over the years, these fixtures of the rural scene went by many names; they were buffers, or duffers, or packmen, or dustyfoots. Some were crooks, but a surprisingly high proportion of them were honest tradesmen, more or less, for it was not possible to built a profitable round without providing customers with a reasonable service. By the middle of the nineteenth century, it has been estimated, an honest packman on the roads of England might earn more than a pound a week, a pretty decent income at that time.

For several hundred years, the packman was a welcome sight to many customers. “He was the one great thrill in the lives of the girls and women,” the writer H.V. Morton tells us, “whose eyes sparkled as he pulled out his trays and offered to their vanity cloths and trifles from the distant town.” Indeed, “the inmates of the farm-house where they locate for the night consider themselves fortunate in having to entertain the packman; for he is their newsmonger, their story-teller and their friend.”

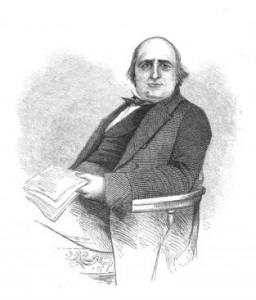

I’m interested here, though, in chronicling the decline and fall of this age-old way of life—for the packman could not survive the coming of the modern world, of course. Exactly when the species became doomed is still debated; in Britain, historians may point to the year 1810, when it became law for peddlers to purchase a pricey annual license in order to carry on their trade. There’s evidence, however, that the packmen prospered for at least a little longer than that; census statistics suggest that the really precipitous decline in their numbers, in England at least, dates to between 1841 and 1851, when the total plunged from more than 17,000 to a mere 2,500, a fall of more than 85 percent. Henry Mayhew, whose lively survey London Labour and the London Poor is our greatest storehouse of information on marginal lives in the Victorian age, noted in 1851 that “the system does not prevail to so great an extent as it did some years back.” Mayhew found that there were then only five packmen and a score of ‘”duffers” and “lumpers” still active in the capital, concluding: “This trade is becoming now almost entirely a country trade.”

Meet the last of the Cornish packmen after the jump.

Henry Mayhew. A pioneering journalist, Mayhew is best remembered as author of the irreplaceable and invaluable London Labour and the London Poor, a four-volume oral history of the mid-Victorian working classes. Image courtesy of Wikicommons

What surprises me, given all the above, is that a handful of packmen lived on in the more remote areas of the country as much as seven decades later. They kept trudging along long after the threepenny bus had wiped them out in London and the railway had reached almost every English settlement of any size—for the most part because, even as late as the middle 1920s, there were still places where the roads were more like paths and the hills sufficiently hazardous to be an obstacle to motor vehicles. Here the remnants of the breed survived, like dinosaurs in some forgotten world. They did so mostly on the Celtic fringe: in the Highlands of Scotland, the hills of mid-Wales, and in the furthest reaches of Cornwall. It was in the last of these, sometime around 1926, and somewhere south of King Arthur’s fortress at Tintagel, that H.V. Morton encountered the man we might reasonably assume to have been the last of the Cornish packmen.

I should pause here for a moment to introduce Morton, who is not often remembered now. He had fought in the Great War, in the heat and dust of Palestine, where he contracted a painful illness and assumed he was about to die. Afflicted by homesickness, Morton “solemnly cursed every moment I had spent wandering foolishly about the world… I was humiliated, mourning there above Jerusalem, to realize how little I knew about England. I was ashamed to think that I had wandered so far and so often over the world neglecting those lovely things near at home… and I took a vow that if the pain in my neck did not end forever in the windy hills of Palestine, I would go home in search of England.”

It was in fulfillment of that vow that Morton, some years later, found himself “bowling along” a country lane west of the Lizard, in the most southerly part of Cornwall. Although he did not know it, he was traveling at pretty much the last moment it was possible to tour the country and confidently greet strangers because “a stranger… was to them a novelty.” And in truth, Morton was also a determined nostalgist, who had deliberately followed a route that took him through all the most beautiful parts of the country, and avoided all the factory towns. Nonetheless, his wistful and often funny evocation of a vanishing country remains readable, and we can be glad that his road took him through the lanes south of St Just, for we have no better account of the traveling packman in his final days than his:

I met him by the side of the road. He was a poor old man and near him was a heavy pack; so I asked if I might give him a lift. “No,” he said, thanking me all the same. I could not give him a lift because the place to which he was going would be inaccessible to “him”— here he pointed to the car.

“To her,” I corrected.

“To she,” he said, meeting me half-way.

“This established contact,” Morton noted, and the two men sat by the side of the road, shared a pipe of tobacco, and talked.

“How long have you been a packman?” I asked him.

I felt the question to be absurd; and it would not have surprised me had he replied: “Well, I began my round, working for Eli of Nablus, general merchant of Sidon, who came over to Britain once a year from 60BC onwards with a cargo of seed pearls, which he swopped for tin. Then when the Romans left I did a rare trade in strops for sword blades.”

“These heere fifty years, sur,” he replied.

“Then you must be nearly seventy?”

“Well, I caan’t tell ‘zactly,” he replied, “but putten one thing agen another, I b’lieve that’s so, sure ’nuff, sur.”

“And you still carry that heavy pack?”

“Yes, sur, I carries him easy, though I do be an old man.”

But for all his years and his burden, Morton’s old man remained resilient:

He pulled off the waterproof and, opening his pack, displayed trays of assorted oddments: cheap shaving brushes, razors, pins, braces, corsets, studs, photograph frames, religious texts, black and white spotted aprons, combs, brushes, and ribbons. The prices were the same as in the small shops.

“I suppose you’ve had to alter your stock from year to year to keep up with fashion?”

“Yes, ’tis true, sur. When I did first take un out on me back there waunt no saafety razors, and the faarm boys had no use for hair grease, and now they be all smurt and gay in town clothes.”

This was the Jazz Age—Morton published his account in 1927—and the packman displayed ‘a smirk of distaste’ when invited to display the newest article in his pack: “clippers to crop shingled heads and many kinds of slides to hold back bobbed hair.”

“In the old days,” he said, “you never saw such hair, I ‘sure ee, as you seed in Cornwall, and the girls bruushed it all day loong – and ’twas lovely to see and now they’ve a-cut it arl off, and if you ax me now what I think about un I tell ee they look like a row of flatpolled cabbages, that un do! ‘Tis different from t’ould days when I soold a packet of hairpins to every wummun I met.”

“We fell to talking,” the account concludes, “of the merits of the packman’s profession.” Like all professions, it had its secrets—but the peddler’s view of its most vital skill of all took Morton by surprise. “Ef you wants to make money at this game,” the packman warned,

“you’ve need of a still tongue on your head, sure I tell ee. There was young Trevissey, when I was a chap, who had haaf the fellows from Penzance to Kynance Cove lookin’ for him with sticks, for young Joe just sopped up stories like a spoonge sops up waater, but un couldn’t hold it. Well, sur, that chap went from faarm to faarm over the length and breadth of the land tellin’ Jennifer Penlee how young Jan Treloar was out courtin’ Mary Taylor over at Megissey. Sur, that chap went through the land sellin’ bootlaces and spreadin’ trouble like youn ever saw! Before that booy had been on his round more than twice there warn’t a maan or wumman who didn’t knaw what every other maan and wumman was wearin’ underneath their clothes, and that’s the truth, sur.”

“What happened to Joe?”

“Why, sur, they got to be too fearful to buy a shoe-string from un! ‘Heere’s young Joe comin’ they’d holler. ‘Shut the doeer fast!’ So un went away, and was never seen again in these paarts.”

We meditated solemnly on the tragedy of this novelist born out of his place. The old man knocked out his pipe and said he must be getting along. He refused assistance, and swung his great pack on his shoulders, waved his stick, and made off over a side-track among the scarred ruins of a dead tin mine. They say that this mine, which stretches beneath the Atlantic, was worked before the time of Christ.

The old figure disappeared among the craters, threading his way carefully, tapping with his stick; and I thought, as I watched him go, that he and the old mine were fellows, equally ancient—for the packman was probably here before the Romans—one outdated and dead: the other poor, old, and lonely, walking slowly along that same sad road.

Envoi

I cannot leave you without recounting another favorite fragment from H.V. Morton’s journey through Cornwall. Here he is, hunched against a thin rain in Sennen churchyard at Land’s End, with the Longships gun sounding its monotonous warning to mariners somewhere in the mist at the very furthest tip of England. He is surveying “the last monuments in a country of monuments” in the apparently vain hope of finding some epitaph of literary merit. And then he sees it…

“The last touch of real poetry in England is written above the grave of Dionysius Williams, who departed this life, aged fifty, on May 15th, 1799:

‘Life speeds away/From point to point, though seeming to stand still/The cunning fugitive is swift by stealth/Too subtle is the movement to be seen/Yet soon man’s hour is up and we are gone.’

I gained a cold thrill from that as I stood in the rain writing it down in a wet book. Is it a quotation? If so, who wrote it? Whenever in future I think of Land’s End I shall see not the jagged rocks and the sea, but that lichened stone lying above Dionysius (who would be 177 years old if he were still alive); that stone and that unlikely name with the rain falling over them, and in the distance a gun booming through the sea fog…”

Sources

Anon. The London Guide, and Stranger’s Safeguard Against the Cheats, Swindlers, and Pickpockets That Abound Within the Bills of Mortality… London: J. Bumpus, 1818; John Badcock. A Living Picture of London, for 1828, and Stranger’s Guide…, by Jon Bee Esq. London: W. Clarke, 1828; Rita Barton (ed). Life in Cornwall in the Mid Nineteenth Century: being extracts from ’The West Briton’ Newspaper in the Two Decades from 1835 to 1854. Truro: Barton, 1971; John Chartres et al (eds). Chapters From the Agrarian History of England and Wales. Cambridge, 4 volumes: CUP, 1990; Laurence Fontaine, History of Pedlars in Europe. Durham: Duke University Press, 1996; Michael Freeman & Derek Aldcroft (eds). Transport in Victorian Britain. Manchester: MUP, 1988; David Hey. Packmen, Carriers and Packhorse Roads: Trade and Communication in North Derbyshire and South Yorkshire. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1980; Roger Leitch. ‘”Here chapman billies tak their stand.” A pilot study of Scottish chapmen, packmen and pedlars.’ Proceedings of the Scottish Society of Antiquarians 120 (1990); Henry Mayhew. London Labour and the London Poor; A Cyclopedia of the Conditions and Earnings of Those That Will Work, Those That Cannot Work, and Those That Will Not Work. Privately published, 4 volumes: London 1851. H.V. Morton. In Search of England. London: The Folio Society, 2002; Margaret Spufford, The Great Reclothing of Rural England – Petty Chapmen & Their Wares in the Seventeenth Century. London: Hambledon, 1984.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)