The Commoner Who Salvaged a King’s Ransom

A furtive antiquarian nicknamed Stoney Jack was responsible for almost every major archaeological find made in London between 1895 and 1939

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Past-Imperfect-Commoner-Kings-Ransom.jpg)

It was only a small shop in an unfashionable part of London, but it had a most peculiar clientele. From Mondays to Fridays the place stayed locked, and its only visitors were schoolboys who came to gaze through the windows at the marvels crammed inside. But on Saturday afternoons the shop was opened by its owner—a “genial frog” of a man, as one acquaintance called him, small, pouched, wheezy, permanently smiling and with the habit of puffing out his cheeks when he talked. Settling himself behind the counter, the shopkeeper would light a cheap cigar and then wait patiently for laborers to bring him treasure. He waited at the counter many years—from roughly 1895 until his death in 1939—and in that time accumulated such a hoard of valuables that he supplied the museums of London with more than 15,000 ancient artifacts and still had plenty left to stock his premises at 7 West Hill, Wandsworth.

“It is,” the journalist H.V. Morton assured his readers in 1928,

perhaps the strangest shop in London. The shop sign over the door is a weather-worn Ka-figure from an Egyptian tomb, now split and worn by the winds of nearly forty winters. The windows are full of an astonishing jumble of objects. Every historic period rubs shoulders in them. Ancient Egyptian bowls lie next to Japanese sword guards and Elizabethan pots contain Saxon brooches, flint arrowheads or Roman coins…

There are lengths of mummy cloth, blue mummy beads, a perfectly preserved Roman leather sandal found twenty feet beneath a London pavement, and a shrunken black object like a bird’s claw that is a mummified hand… all the objects are genuine and priced at a few shillings each.

H.V. Morton, one of the best-known British journalists of the 1920s and 1930s, often visited Lawrence’s shop as a young man, and wrote a revealing and influential pen-portrait of him.

This higgledy-piggledy collection was the property of George Fabian Lawrence, an antiquary born in the Barbican area of London in 1861—though to say that Lawrence owned it is to stretch a point, for much of his stock was acquired by shadowy means, and on more than one occasion an embarrassed museum had to surrender an item it had bought from him.

For the better part of half a century, however, august institutions from the British Museum down winked at his hazy provenances and his suspect business methods, for the shop on West Hill supplied items that could not be found elsewhere. Among the major museum pieces that Lawrence obtained and sold were the head of an ancient ocean god, which remains a cornerstone of the Roman collection at the Museum of London; a spectacular curse tablet in the British Museum, and the magnificent Cheapside Hoard: a priceless 500-piece collection of gemstones, broaches and rings excavated from a cellar shortly before the First World War. It was the chief triumph of Lawrence’s career that he could salvage the Hoard, which still comprises the greatest trove of Elizabethan and Stuart-era jewelery ever unearthed.

Lawrence’s operating method was simple but ingenious. For several decades, he would haunt London’s building sites each weekday lunch hour, sidling up to the laborers who worked there, buying them drinks and letting them know that he was more than happy to purchase any curios—from ancient coins to fragments of pottery—that they and their mates uncovered in the course of their excavations. According to Morton, who first visited the West Hill shop as a wide-eyed young man around 1912, and soon began to spend most of his Saturday afternoons there, Lawrence was so well known to London’s navvies that he was universally referred to as “Stoney Jack.” A number, Morton added, had been offered “rudimentary archaeological training,” by the antiquary, so they knew what to look for.

Lawrence made many of his purchases on the spot; he kept his pockets full of half-crowns (each worth two shillings and sixpence, or around $18.50 today) with which to reward contacts, and he could often be spotted making furtive deals behind sidewalk billboards and in barrooms. His greatest finds, though were the ones that wended their way to Wandsworth on the weekends, brought there wrapped in handkerchiefs or sacks by navvies spruced up in their Sunday best, for it was only then that laborers could spirit their larger discoveries away from the construction sites and out from under the noses of their foremen and any landlords’ representatives. They took such risks because they liked and trusted Lawrence—and also, as JoAnn Spears explains it, because he “understood networking long before it became a buzzword, and leveraged connections like a latter-day Fagin.”

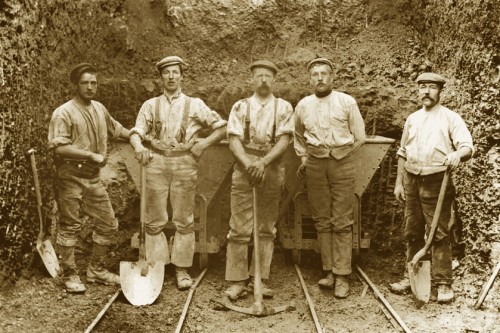

London navvies–laborers who excavated foundations, built railways and dug tunnels, all by hand–uncovered thousands of valuable artefacts in the British capital each year.

Two more touches of genius ensured that Stoney Jack remained the navvies’ favorite. The first was that he was renowned for his honesty. If ever a find sold for more than he had estimated it was worth, he would track down the discoverer and make certain he received a share of the profits. The second was that Lawrence never turned a visitor away empty-handed. He rewarded even the most worthless discoveries with the price of half a pint of beer, and the workmen’s attitude toward his chief rival—a representative of the City of London’s Guildhall Museum who earned the contemptuous nickname “Old Sixpenny”—is a testament to his generosity.

Lawrence lived at just about the time that archaeology was emerging as a professional discipline, but although he was extremely knowledgeable, and enjoyed a long career as a salaried official—briefly at the Guildhall and for many years as Inspector of Excavations at the newer Museum of London—he was at heart an antiquarian. He had grown up as the son of a pawnbroker and left school at an early age; for all his knowledge and enthusiasm, he was more or less self-taught. He valued objects for themselves and for what they could tell him about some aspect of the past, never, apparently, seeing his discoveries as tiny fragments of some greater whole.

To Lawrence, Morton wrote,

the past appeared to be more real, and infinitely more amusing, than the present. He had an almost clairvoyant attitude to it. He would hold a Roman sandal—for leather is marvelously preserved in the London clay—and, half closing his eyes, with his head on one side, his cheroot obstructing his diction, would speak about the cobbler who had made it ages ago, the shop in which it had been sold, the kind of Roman who had probably brought it and the streets of the long-vanished London it had known.

The whole picture took life and colour as he spoke. I have never met anyone with a more affectionate attitude to the past.

Like Morton, who nursed a love of ancient Egypt, Stoney Jack acquired his interest in ancient history during his boyhood. “For practical purposes,” he told another interviewer, “let us say 1885, when as a youth of 18 I found my first stone implement…. It chanced that one morning I read in the paper of the finding of some stone implements in my neighborhood. I wondered if there were any more to be found. I proceeded to look for them in the afternoon, and was rewarded.”

A Roman “curse tablet”, recovered by Lawrence from an excavation in Telegraph Street, London, is now part of the collection of the British Museum.

Controversial though Lawrence’s motives and his methods may have been, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that he was the right man in the right place to save a good deal of London’s heritage. Between 1890 and 1930 the city underwent redevelopment at a pace unheard of since the Great Fire of 1666; old buildings were demolished and replaced with newer, taller ones that required deeper foundations. In the days before the advent of widespread mechanization in the building trade, much of the necessary digging was done by navvies, who hacked their way down through Georgian, Elizabethan, medieval and finally Saxon and Roman strata that had not been exposed for centuries.

It was a golden age for excavation. The relatively small scale of the work—which was mostly done with picks and shovels—made it possible to spot and salvage minor objects in a way no longer practicable today. Even so, no formal system existed for identifying or protecting artifacts, and without Lawrence’s intervention most if not all of the 12,000 objects he supplied to the Museum of London, and the 300 and more catalogued under his name at the British Museum, would have been tipped into skips and shot into Thames barges to vanish into landfill on the Erith marshes. This was very nearly the fate of the treasure with which Stoney Jack will always be associated: the ancient bucket packed to the brim with a king’s ransom worth of gems and jewelery that was dug out of a cellar in the City of London during the summer of 1912.

It is impossible to say for certain who uncovered what would become known as the Cheapside Hoard, exactly where they found it, or when it came into the antiquary’s possession. According to Francis Sheppard, the date was June 18, 1912, and the spot an excavation on the corner of Friday Street and Cheapside in a district that had long been associated with the jewelery trade. That may or may not be accurate; one of Lawrence’s favorite tricks was to obscure the precise source of his most valued stock so as to prevent suspicious landowners from lodging legal claims.

This dramatic pocket watch, dated to c.1610 and set in a case carved from a single large Colombian emerald, was one of the most valuable of the finds making up the Cheapside Hoard–and led historian Kris Lane to put forward a new theory explaining the Hoard’s origins. Photo: Museum of London.

Whatever the truth, the discovery was a spectacular one whose value was recognized by everyone who saw it—everyone, that is, but the navvies who uncovered the Hoard in the first place. According to Morton, who claimed to have been present as a boy when the find was brought to West Hill by its discoverers one Saturday evening, the workmen who had uncovered it believed that they had “struck a toyshop.” Tipping open a sack, the men disgorged an enormous lump of clay resembling “an iron football, the journalist recalled, “and they said there was a lot more of it. When they had gone, we went up to the bathroom and turned the water on to the clay. Out fell pearl earrings and pendants and all kinds of crumpled jewellery.”

For the most accurate version of what happened next, it is necessary to turn to the records of the Museum of London, which reveal that the discovery caused so much excitement that a meeting of the museum’s trustees was convened at the House of Commons the next evening, and the whole treasure was assembled for inspection a week later. “By that time,” Sheppard notes, “Lawrence had somehow or other got hold of a few more jewels, and on June 26 sent him a cheque for £90…. Whether this was the full amount paid by the trustees for the hoard is not clear. In August 1913 he was paid £47 for unspecified purchases for the museum.”

Morton—who was 19 at the time of the discovery—offered a more romantic account many years later: “I believe that Lawrence declared this as treasure trove and was awarded a large sum of money, I think a thousand pounds. I well remember that he gave each of the astounded navvies something like a hundred pounds each, and I was told that these men disappeared, and were not seen again for months!”

Whatever the truth, the contents of the navvies’ bucket were certainly astonishing. The hoard consisted of several hundred pieces—some of them gems, but most worked pieces of jewelery in a wide variety of styles. They came from all over the world; among the most spectacular pieces were a number of cameos featuring Roman gods, several fantastical jewels from Mughal India, a quantity of superb 17th-century enamelware, and a large hinged watch case carved from a huge emerald.

A finely-worked salamander brooch, typical of the intricate Stuart-era jewelry that made up the Cheapside Hoard. Photo: Museum of London.

The collection was tentatively dated to around 1600-1650, and was rendered particularly valuable by the ostentatious fashions of the time; many of the pieces had bold, complex designs that featured a multiplicity of large gems. It was widely assumed, then and now, that the Cheapside Hoard was the stock-in-trade of some Stuart-era jeweler that had been buried for safekeeping some time during the Civil War that shattered England, Ireland and Scotland between 1642 and 1651, eventually resulting in the execution of Charles I and the establishment of Oliver Cromwell’s short-lived puritan republic.

It is easy to imagine some hapless jeweler, impressed into the Parliamentarian army, concealing his valuables in his cellar before marching off to his death on a distant battlefield. More recently, however, an alternative theory has been advanced by Kris Lane, an historian at Tulane whose book The Color of Paradise: The Emerald in the Age of Gunpowder Empires suggests that the Cheapside Hoard probably had its origins in the great emerald markets of India, and may once have belonged to a Dutch gem merchant named Gerard Polman.

The story that Lane spins goes like this: Testimonies recorded in London in 1641 show that, a decade earlier, Polman had booked passage home from Persia after a lifetime’s trading in the east. He had offered £100 or £200 to the master of an East India Company ship Discovery in Gombroon, Persia, to bring him home to Europe, but got no further than the Comoros Islands before dying–possibly poisoned by the ship’s crew for his valuables. Soon afterwards, the carpenter’s mate of the Discovery, one Christopher Adams, appropriated a large black box, stuffed with jewels and silk, that had once belonged to Polman. This treasure, the testimonies state, was astonishingly valuable; according to Adams’s wife, the gems it contained were “so shiny that they thought the cabin was afire” when the box had first been opened in the Indian Ocean. “Other deponents who had seen the jewels on board ship,” adds Lane, “said they could read by their brilliance.”

Cheapside–for many years center of London’s financial district district, but in Stuart times known for its jewelry stores–photographed in c.1900.

It is scarcely surprising, then, that when the Discovery finally hove to off Gravesend, at the mouth of the Thames, at the end of her long voyage, Adams jumped ship and went ashore in a small boat, taking his loot with him. We know from the Parliamentary archive that he made several journeys to London to fence the jewels, selling some to a man named Nicholas Pope who kept a shop off Fleet Street.

Soon, however, word of his treachery reached the directors of the East India Company, and Adams was promptly taken into custody. He spent the next three years in jail. It is the testimony that he gave from prison that may tie Polman’s gems to the Cheapside Hoard.

The booty, Adams admitted, had included “a greene rough stone or emerald three inches long and three inches in compass”—a close match for the jewel carved into a hinged watch case that Stoney Jack recovered in 1912. This jewel, he confessed, “was afterward pawned at Cheapside, but to whom he knoweth not”, and Lane considers it a “likely scenario” that the emerald found its way into the bucket buried in a Cheapside cellar; “many of the other stones and rings,” he adds, “appear tantalizingly similar to those mentioned in the Polman depositions.” If Lane is right, the Cheapside Hoard may have been buried in the 1630s, to avoid the agents of the East India Company, rather than lost during the chaos of the Civil War.

Whether or not Lane’s scholarly detective work has revealed the origins of the Cheapside Hoard, it seems reasonable to ask whether the good that Stoney Jack Lawrence did was enough to outweigh the less creditable aspects of his long career. His business was, of course, barely legitimate, and, in theory, his navvies’ finds belonged to the owner of the land that they were working on—or, if exceptionally valuable, to the Crown. That they had to be smuggled off the building sites, and that Lawrence, when he catalogued and sold them, chose to be vague about exactly where they had been found, is evidence enough of his duplicity.

A selection of the 500 pieces making up the Cheapside Hoard that were recovered from a ball of congealed mud and crushed metalwork resembling an “iron football” uncovered in the summer of 1912. Photo: Museum of London.

Equally disturbing, to the modern scholar, is Lawrence’s willingness to compromise his integrity as a salaried official of several museums by acting as both buyer and seller in hundreds of transactions, not only setting his own price, but also authenticating artifacts that he himself supplied. Yet there is remarkably little evidence that any institution Lawrence worked for paid over the odds for his discoveries, and when Stoney Jack died, at age 79, he left an estate totaling little more than £1,000 (about $87,000 now). By encouraging laborers to hack treasures from the ground and smuggle them out to him, the old antiquary also turned his back on the possibility of setting up regulated digs that would almost certainly have turned up additional finds and evidence to set his greatest discoveries in context. On the other hand, there were few regulated digs in those days, and had Lawarence never troubled to make friends with London navvies, most of his finds would have been lost for ever.

For H.V. Morton, it was Stoney Jack’s generosity that mattered. “He loved nothing better than a schoolboy who was interested in the past,” Morton wrote. “Many a time I have seen a lad in his shop longingly fingering some trifle that he could not afford to buy. ‘Put it in your pocket,’ Lawrence would cry. ‘I want you to have it, my boy, and–give me threepence!‘”

But perhaps the last word can be left to Sir Mortimer Wheeler, something of a swashbuckler himself, but by the time he became keeper of the Museum of London in the 1930s–after Stoney Jack had been forced into retirement for making one illicit purchase too many outside a guarded building site–a pillar of the British archaeological establishment.

“But for Mr Lawrence,” Wheeler conceded,

not a tithe of the objects found during building or dredging operations in the neighborhood of London during the last forty years would have been saved to knowledge. If on occasion a remote landowner may, in the process, theoretically have lost some trifle that was his just due, a higher justice may reasonably recognize that… the representative and, indeed, important prehistoric, Roman, Saxon and medieval collections of the Museum are largely founded upon this work of skillful salvage.

Sources

Anon. “Saved Tudor relics.” St Joseph News-Press (St Joseph, MO), August 3, 1928; Anon. “Stoney Jack’s work for museum.” Straits Times (Singapore), August 1, 1928; Michael Bartholomew. In Search of HV Morton. London: Methuen, 2010; Joanna Bird, Hugh Chapman & John Clark. Collectanea Loniniensia: Studies in London Archaeology and History Presented to Ralph Merrifield. London: London & Middlesex Archaeological Society, 1978; Derby Daily Telegraph, November 20, 1930; Exeter & Plymouth Gazette, March 17, 1939; Gloucester Citizen, July 3, 1928; Kris E. Lane. The Colour of Paradise: the Emerald in the Age of Gunpowder Empires. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010; J. MacDonald. “Stony Jack’s Roman London.” In J. Bird, M. Hassall and Harvey Sheldon, Interpreting Roman London. Oxbow Monograph 58 (1996); Ivor Noël Hume. A Passion for the Past: the Odyssey of a Transatlantic Archaeologist. Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press, 2010; Arthur MacGregor. Summary Catalogue of the Continental Archaeological Collections. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1997; Francis Sheppard. Treasury of London’s Past. London: Stationery Office, 1991; HV Morton. In Search of London. Boston: Da Capo Press, 2002; Derek Sherborn. An Inspector Recalls. London: Book Guild, 2003; JoAnn Spears. “The Cheapside Hoard.” On the Tudor Trail, February 23, 2012. Accessed June 4, 2013; Peter Watts. “Stoney Jack and the Cheapside Hoard.” The Great Wen, November 18, 2010. Accessed June 4, 2013.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)