The Story Behind Rube Goldberg’s Complicated Contraptions

In his time he was a world-famous cartoonist, but today he’s best known for these wacky inventions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/51/075114f2-5108-4286-9841-e6cafb6a3c66/09_rg_rube_goldberg_inventions_usps_stamp.jpg)

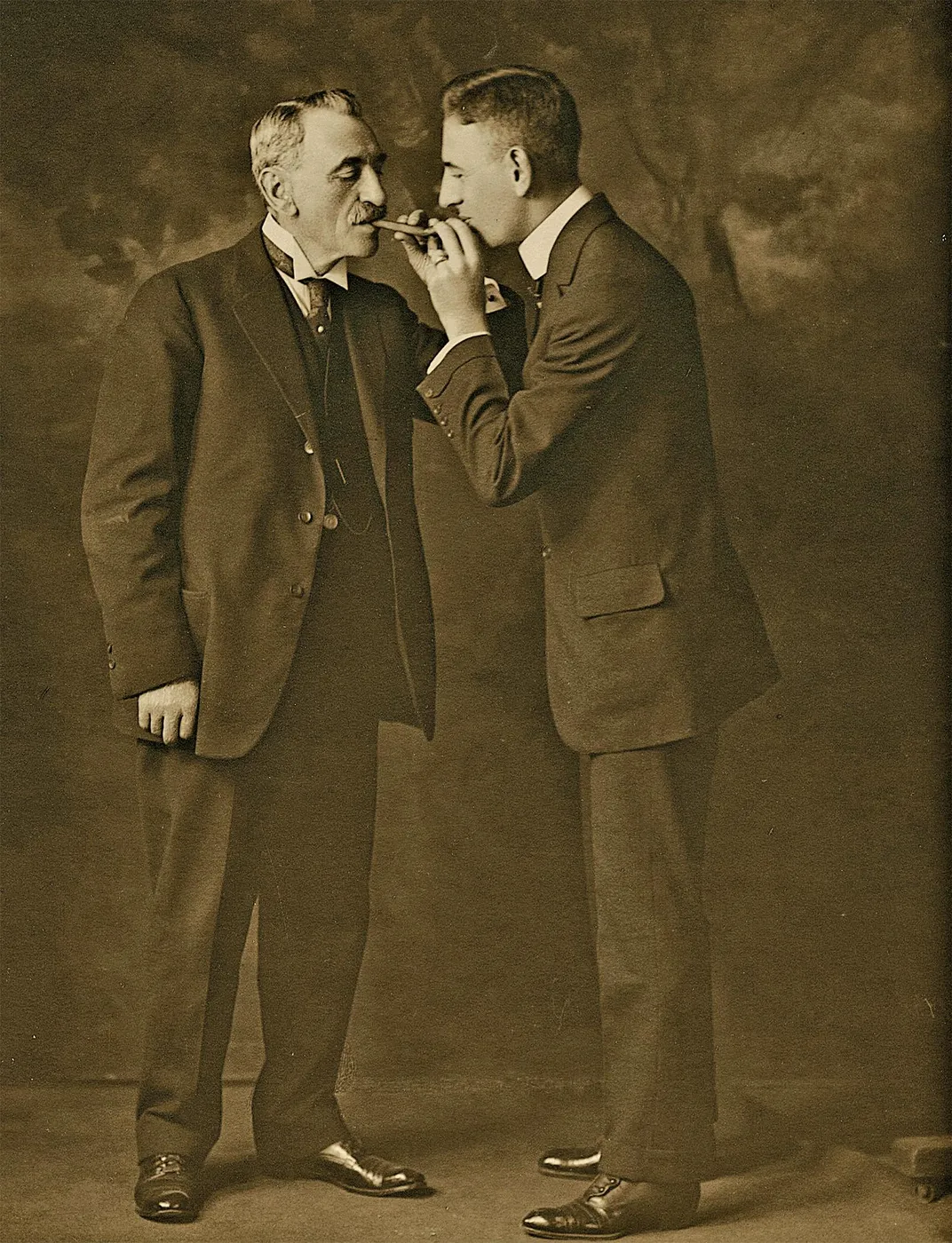

During his 72-year career, cartoonist Rube Goldberg produced more than 50,000 drawings and thousands of comic strips. In 1922, Goldberg was so sought after that a newspaper syndicate paid him $200,000 for his comic strips – the equivalent of around $2.3 million today, and in the ’40s and ‘50s, he was famous enough to endorse products like cough drops, socks and Lucky Strike cigarettes (although he personally only smoked cigars.)

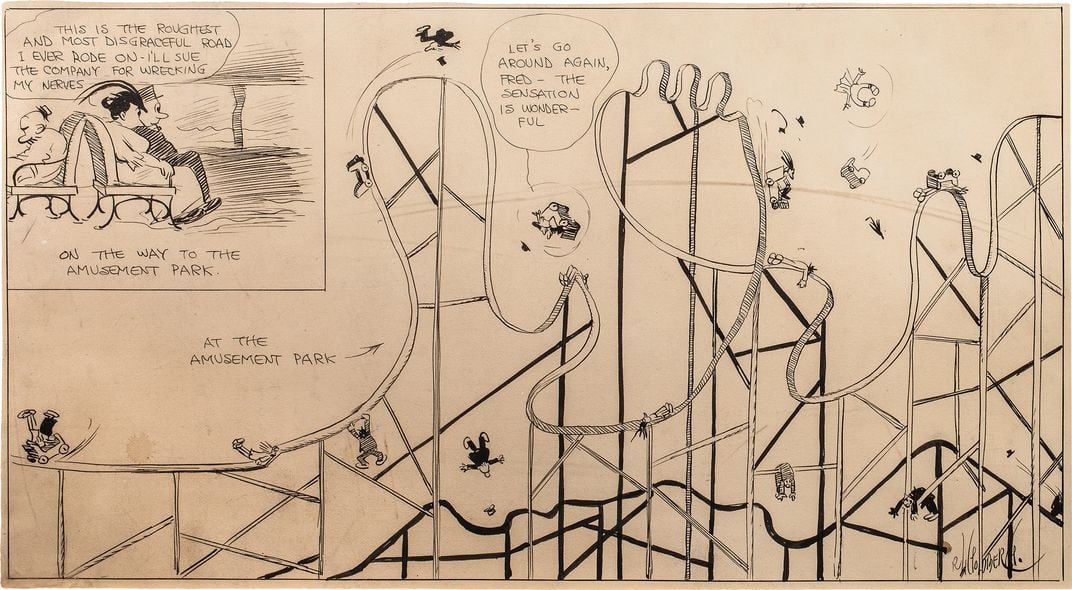

But today his name is an eponym for his famed “invention drawings,” designs of overly complicated machines: using things like pulleys, levers, birds, and rockets to fix simple problems like fishing an olive out of a tall jar, or remembering to mail a letter to your wife. Goldberg approached them as a tongue-in-cheek critique of the havoc wrought by industrialization and put forward the idea that technology, intended to simplify people’s lives could have the opposite effect.

Goldberg, a San Francisco native who studied engineering at University of California, Berkeley, is, according to his estate, the only person whose name is used as an adjective in the dictionary. As early as 1931, the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defined “Rube Goldberg” as “accomplishing by complex means what seemingly could be done simply.”

Goldberg’s drawings, sketches, and cartoons, as well photographs, films, letters, and memorabilia from his life, is exhibited in The Art of Rube Goldberg, open now at San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum, the first retrospective of the artist’s work since a show 1970 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of History and Technology (today known as the American History Museum).

Renny Pritikin, a curator at the museum, says Goldberg’s influence on American culture is hard to overstate. “In the teens and early 20s, before radio and TV, cartoonists were rock stars,” he says. “The Sunday newspaper was one of the main sources of entertainment and culture and he had four or five strips that appeared in cities and towns all over the country.

As a kid, Goldberg loved to draw, but he never took formal lessons, except for some with a professional sign painter – something he was proud of later in life. At 12, he won first prize at his school for a drawing called, The Old Violinist; it’s on view at the exhibit. After graduating from the University of California, Berkeley, with a degree in mining engineering, Goldberg worked for a time for San Francisco City Engineer’s Office, Water and Sewers Department, but he disliked the job so much and was so determined to draw for a living that he took a job as a sports cartoonist at the San Francisco Chronicle for less then a third of the salary his engineering job paid.

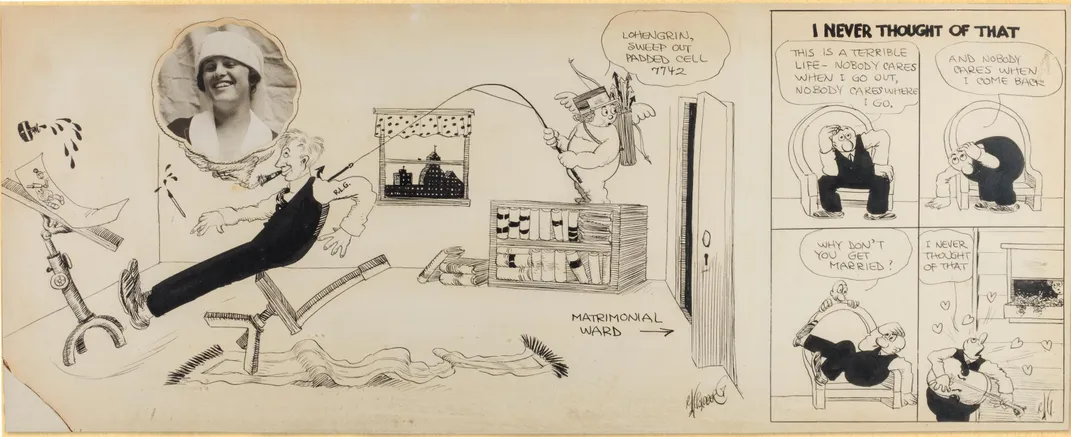

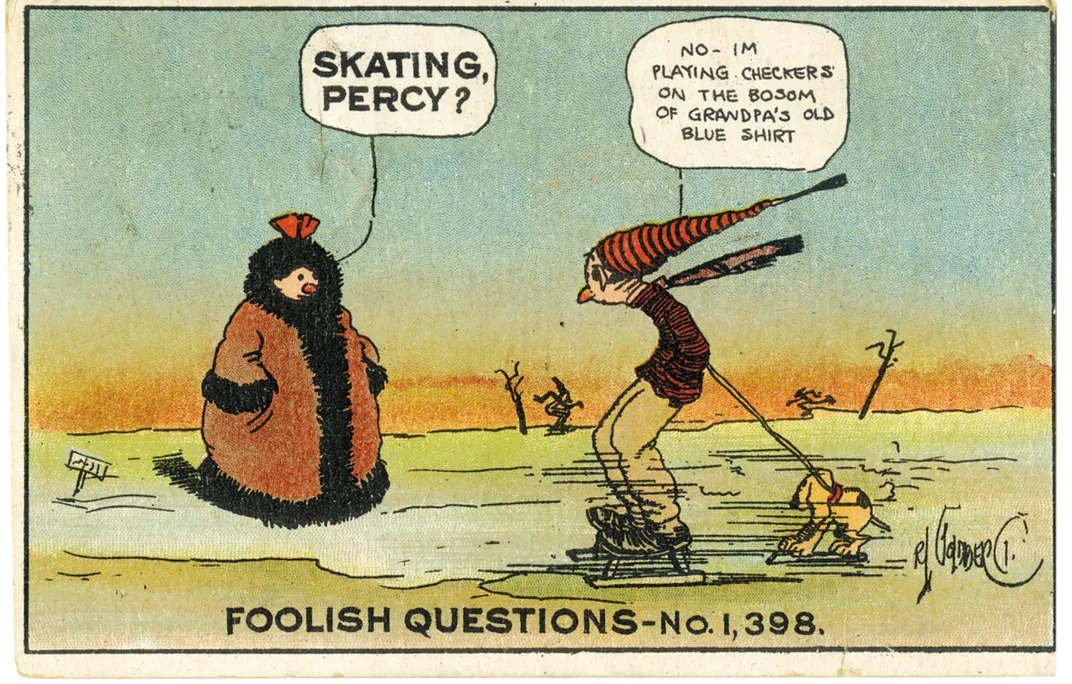

Goldberg yearned to move to New York, which he called, “the front row,” so he took a train across the country, landing a job at The New York Evening Mail, where he created comic strips and single-frame cartoons like "Boob McNutt," "Lala Palooza," “Mike and Ike—They Look Alike” and "Foolish Questions," all of which would become nationally syndicated.

A single-panel cartoon, “Foolish Questions” showcased Goldberg’s humor (which, to be fair, hasn’t really held up over the decades) with his subjects giving sarcastic answers to obvious questions such as: “Are you cold?” “No, you musk ox – I’m shivering because I’m thinking how expensive prunes are in Egypt.” In another comic, a woman asks a man standing on a frozen lake with on blades on his feet, “Skating. Percy?” to which he answers, “No, –I’m playing checkers on the bosom of grandpa’s old blue shirt.”

These were so popular that the public started sending in their own foolish questions, said Pritikin, who calls this an early example of crowdsourcing.

“He could find humor in absurd situations and deliver them with a straightforward sophistication,” Pritikin said. “He was a rock star of his time, and he had an influence on how people joked around.”

The first complex contraption that would end up being his most famous invention was his “Automatic Weight Reducing Machine,” drawn in 1914, which used a donut, bomb, balloon and a hot stove to trap an obese person in a room without food, who had to lose weight to get free.

In the late 20s, Goldberg started a series called “The Inventions of Professor Lucifer G. Butts” that was heavily influenced by his earlier job drawing sewer pipes for the San Francisco government. The museum devotes an entire room to the drawings, highlighting Goldberg’s bemusement at how technological innovation can go wrong, such as “Discovery of a Sure Way to Keep the Head Down During a Golf Shot” and “An Idea to Keep You from Forgetting Your Wife's Letter.”

Goldberg would later move into more newsworthy endeavors, drawing cartoons in the ’30s as a reaction to the rise of fascism in Europe. Another, drawn in 1945, includes two parallel tracks in the desert, one labeled Arabs and one Jews, and a third, 1947 cartoon titled “Peace Today,” shows a nuclear bomb balanced on a precipice; it won him the Pulitzer Prize.

Now a semi-retired clinical psychologist living in New Jersey, John George, Goldberg’s grandson, spent weekends and summers with his grandfather, and was well aware of his fame.

“This was in the ’50s and ’60s, not his heyday, but he was still very big, so you’d never wait in line for a restaurant, you’d go on TV shows, people would come up to him, ‘Oh, Mr. Goldberg, this, that and the other,’” George recalls. “So you were out in the world with a big celebrity, and then you’d come home to a regular person. He was able to be both and I think enjoyed both.”

Goldberg’s career was remarkable both for its length and variety, Pritikin says. He was prescient, at least in the example of a Forbes magazine cover illustrated by Goldberg. Called “The Future of Home Entertainment,” it shows a family in their living room, with everyone, including the cat, watching their own flat screen TV and ignoring one another.

He drew it in 1967.

Editor's note, June 7, 2018: This article has been changed to reflect that Renny Pritikin is the curator of the San Francisco Contemporary Jewish Museum, not the Goldberg exhibit itself.