The Search Is On for the Site of the Worst Indian Massacre in U.S. History

At least 250 Shoshone were killed by the Army in the 1863 incident, but their remains have yet to be found

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/51/99517799-1615-4957-9638-a9d97409f405/excavating_metal_detection_hits.jpg)

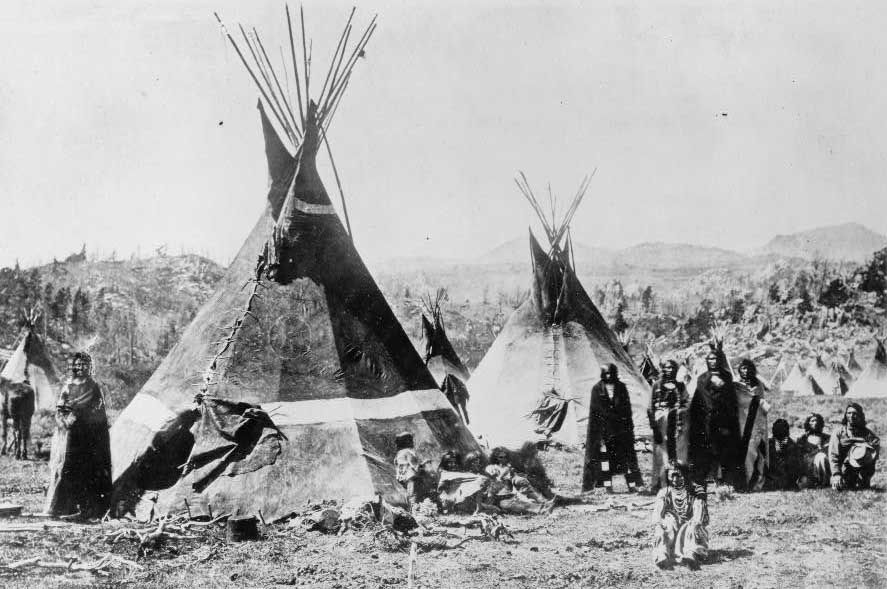

In the frigid dawn of January 29, 1863, Sagwitch, a leader among the Shoshone of Bia Ogoi, or Big River, in what is now Idaho, stepped outside his lodge and saw a curious band of fog moving down the bluff toward him across a half-frozen river. The mist was no fog, though. It was steam rising in the subzero air from hundreds of U.S. Army foot soldiers, cavalry and their horses. The Army was coming for his people.

Over the next four hours, the 200 soldiers under Colonel Patrick Connor’s command killed 250 or more Shoshone, including at least 90 women, children and infants. The Shoshone were shot, stabbed and battered to death. Some were driven into the icy river to drown or freeze. The Shoshone men, and some women, meanwhile, managed to kill or mortally wound 24 soldiers by gunfire.

Historians call the Bear River Massacre of 1863 the deadliest reported attack on Native Americans by the U.S. military—worse than Sand Creek in 1864, the Marias in 1870 and Wounded Knee in 1890.

It is also the least well known. In 1863, most of the nation’s attention was focused on the Civil War, not the distant western territories. Only a few eyewitness and secondhand accounts of the incident were published at the time in Utah and California newspapers. Local people avoided the site, with its bones and shanks of hair, for years, and the remaining Bia Ogoi families quietly dispersed. But their descendants still tell the tale of that long-ago bloody day, and now archaeologists are beginning to unearth the remains of the village that didn’t survive.

Darren Parry, a solemn man who is a council member of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation and Sagwitch’s great-great-great grandson, stands on a hill named Cedar Point. He looks down on the historic battlefield in its braided river valley. An irrigation canal curves along the base of the bluffs, and a few pickup trucks drive along U.S. Highway 91, following a route used by the Shoshone 200 years ago.

These alterations to the landscape—roads, farms and an aqueduct, along with shifts in the river’s meandering course through the valley—have made it difficult, from a scientist’s perspective, to pinpoint the location of the Shoshone winter village. Parry, though, does not have this problem.

“This spot overlooks everything that was important to our tribe,” he says. “Our bands wintered here, resting and spending time with family. There are warmer places in Utah, but here there are hot springs, and the ravine for protection from storms.”

The So-So-Goi, or People Who Travel on Foot, had been living well on Bia Ogoi for generations. All their needs—food, clothes, tools and shelter—were met by the rabbits, deer, elk and bighorn sheep on the land, the fish in the river, and the camas lilies, pinyon nuts and other plants that ripened in the short, intense summers. They lived in loose communities of extended families and often left the valley for resources such as salmon in Oregon and bison in Wyoming. In the cold months, they mostly stayed in the ravine village, eating carefully stored provisions and occasional fresh meat.

White-skinned strangers came through the mountain passes into the valley seeking beaver and other furs. These men gave the place a new name, Cache Valley, and the year a number, 1825. They gave the So-So-Goi a new name, too—Shoshone. The Shoshone traded with the hunters and trappers, who were little cause for concern since they were few in number and only passing through.

But then people who called themselves Mormons came to the northern valley. The Mormons were looking for a place where they, too, could live well. They were many in number, and they stayed, calling this place Franklin. The newcomers cut down trees, built cabins, fenced the land to keep in livestock, plowed the meadows for crops and hunted the remaining game. They even changed Big River’s name to Bear.

At first, relations between the Shoshone and the Mormons were cordial. The settlers had valuable things to trade, such as cooking pots, knives, horses and guns. And the Shoshone knowledge of living off the land was essential when the Mormons’ first crops failed.

But eventually, the Shoshone “became burdensome beggars” in the eyes of the Mormons, writes Kenneth Reid, Idaho’s state archaeologist and director of the Idaho State Historic Preservation Office, in a new summary of the massacre for the U.S. National Park Service’s American Battlefield Protection Program. “Hunger, fear and anger prompted unpredictable transactions of charity and demand between the Mormon settlers and the increasingly desperate and defiant Shoshones. The Indians pretended to be friendly, and the Mormons pretended to take care of them, but neither pretense was very reassuring to the opposite party.”

In Salt Lake City, the territorial commissioner of Indian affairs was well aware of the growing discord between the two peoples and hoped to resolve it through treaty negotiations that would give the Shoshones land—somewhere else, of course—and food. Conflict continued, however, and when a small group of miners was killed, Army Colonel Connor resolved to “chastise” those he believed responsible—the Shoshone people living in the ravine in the northern valley at the confluence of a creek and the Bear River.

Pointing below Cedar Point, Parry says, “My grandmother told me that her grandfather [Sagwitch’s son Yeager, who was 12 years old and survived the massacre by pretending to be dead] told her that all the tipis were set up right here in the ravine and hugging the side of the mountain.” He continues, “Most of the killing took place between here and the river. Because the soldiers drove the people into the open and into the river.”

In 2013, the Idaho State Historical Society began efforts to map and protect what may remain of the battlefield. The following year, archaeologists Kenneth Cannon, of Utah State University and president of USU Archeological Services, and Molly Cannon, director of the Museum of Anthropology at Utah State, started investigating the site.

Written and oral accounts of the events at Bear River suggested the Cannons would find remains from the battle in a ravine with a creek that flowed into the river. And soon they did find artifacts from the post-massacre years, such as buckles, buttons, barbed wire and railroad spikes. They even found traces of a prehistoric hearth from around 900 A.D.

But their primary goal, the location of the Shoshone-village-turned-killing-ground, proved elusive. There should have been thousands of bullets that had been fired from rifles and revolvers, as well as the remnants of 70 lodges that had sheltered 400 people—post-holes, hardened floors, hearths, pots, kettles, arrowheads, food stores and trash middens.

Yet of this core objective, the scientists found only one piece of hard evidence: a spent .44-caliber round lead ball of that period that could have been fired by a soldier or warrior.

The Cannons dove back into the data. Their team combined historic maps with magnetometer and ground-penetrating-radar studies, which showed potential artifacts underground, and geomorphic maps that showed how floods and landslides had reshaped the terrain. That’s when they found “something really exciting,” says Kenneth Cannon.

“The three different types of data sources came together to support the notion that the Bear River, within a decade of the massacre, shifted at least 500 yards to the south, to its present location,” he says.

The archaeologists now suspect that the site where the heaviest fighting and most deaths occurred has been buried by a century of sediment, entombing all traces of the Shoshone. “We had been looking in the wrong place,” Kenneth Cannon says. If his team can get funding, the Cannons will return to the Bear River valley this summer to resume their search for Bia Ogoi.

Though the exact site of the village is still unknown, the massacre that destroyed it may finally be getting the attention it deserves. In 2017, the Idaho State Museum in Boise will host an exhibit on the Bear River Massacre. And the Northwestern Shoshone are in the process of acquiring land in the area for an interpretive center that would describe the the lives of their ancestors in the Bear River valley, the conflicts between native people and European immigrants and the killings of 1863.

This is a story, Parry says, that needs to be told.

Editor's Note, May 13, 2016: After publishing, two corrections were made to this story. First, a sentence was clarified to indicate that archaeologists found evidence of a prehistoric hearth, not a dwelling. Second, a sentence was removed to avoid the implication that the scientists are looking for or collecting human bones as part of their research.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sylvia_Wright_head_shot.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sylvia_Wright_head_shot.jpg)