Saving the Jews of Nazi France

As Jews in France tried to flee the Nazi occupation, Harry Bingham, an American diplomat, sped them to safety

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Harry-Bingham-Marseille-631.jpg)

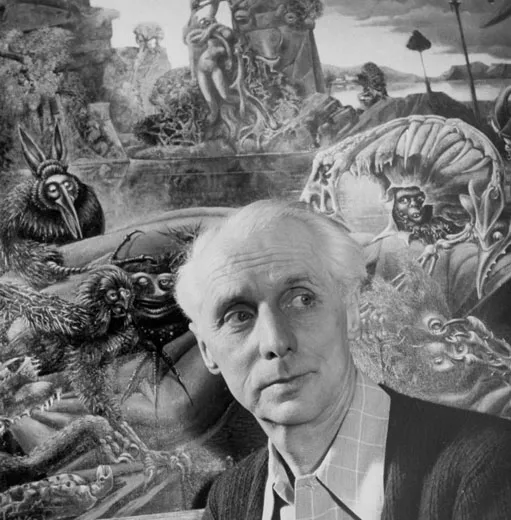

An internationally known german novelist, Lion Feuchtwanger had been a harsh critic of Adolf Hitler since the 1920s. One of his novels, The Oppermanns, was a thinly veiled exposé of Nazi brutality. He called the Führer's Mein Kampf a 140,000-word book with 140,000 mistakes. "The Nazis had denounced me as Enemy Number One," he once said. They also stripped him of his German citizenship and publicly burned his books.

In July 1940, the Nazis had just occupied Paris, and southeastern France—where Feuchtwanger was living—was controlled by a French government with Nazi sympathies. As the French authorities in the south began rounding up the foreigners in their midst, Feuchtwanger found himself in a lightly guarded detention camp near Nîmes, fearing imminent transfer to the Gestapo. On the afternoon of Sunday, July 21, he took a walk by a swimming hole where inmates were allowed to bathe, debating whether to flee the camp or wait for exit papers that the French had promised.

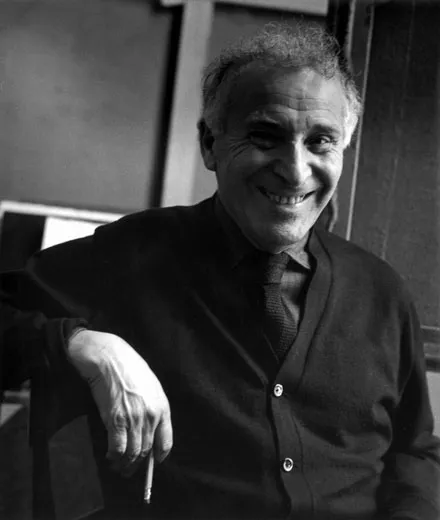

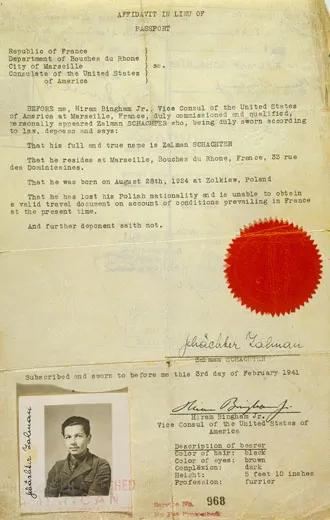

Suddenly, he spotted a woman he knew along the road to the camp and hurried over. "I have been waiting for you here," she said, shepherding him to a car. A few hours later, the novelist was safely in Marseille, enjoying the hospitality of a low-ranking U.S. diplomat named Hiram Bingham IV. Bingham, 37, was descended from prominent politicians, social scientists and missionaries. His grandfather's book A Residence of Twenty-One Years in the Sandwich Islands presaged James Michener's Hawaii. His father, Hiram Bingham III, was a renowned explorer and, later, a U.S. senator. After a prep school and Ivy League education, Hiram, known as Harry, seemed destined for a brilliant career in the Foreign Service.

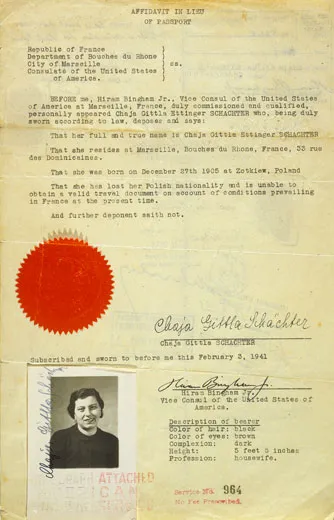

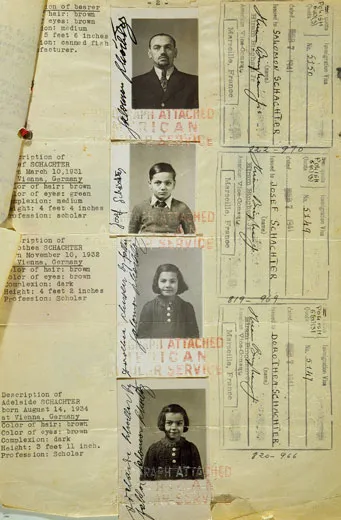

But as World War II approached, Bingham made a series of life-altering choices. By sheltering Feuchtwanger in his private villa, Bingham violated both French law and U.S. policy. To draw attention to hunger and disease in the French camps, he challenged indifference and anti-Semitism among his State Department superiors. In speeding up visa and travel documents at the Marseille consulate, he disobeyed orders from Washington. In all, an estimated 2,500 refugees were able to flee to safety because of Bingham's help. Some of his beneficiaries were famous—Marc Chagall, Hannah Arendt, Max Ernst—but most were not.

Bingham accomplished all this in a mere ten months—until the State Department summarily transferred him out of France. By the end of World War II, his hopes of becoming an ambassador had been dashed. At the age of 42, after more than ten years in the Foreign Service, he moved with his wife and growing family to the farm they owned in Salem, Connecticut, where he spent the rest of his days painting landscapes and Chagallesque abstracts, playing the cello and dabbling in business ventures that never amounted to much.

When Bingham died there in 1988, at 84, the stories about his service in Marseille remained untold. William Bingham, 54, the youngest of his 11 children, says he and his siblings "never knew why his career had soured." But after their mother, Rose, died in 1996, at 87, they found out.

While cleaning out a dusty closet behind the main fireplace in the 18th-century farmhouse, William discovered a tightly bound bundle of documents that outlined his father's wartime service. Thus began a campaign to vindicate his father. And as his rescue efforts came to light, he was embraced by the same government that had cast him aside.

Hiram Bingham IV was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on July 17, 1903. His mother, Alfreda Mitchell, was a granddaughter of Charles L. Tiffany, the founder of Tiffany & Co. Harry's father, Hiram Bingham III, had no interest in following his parents as Protestant missionaries in the South Pacific. Starting in 1911, he led a series of expeditions to Machu Picchu in the Peruvian Andes; his travelogue, Lost City of the Incas, made him world-renowned. After his South American adventures, the senior Bingham entered the Army in 1917 as an aviator, achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel and was a flight instructor in France. A Republican, he served Connecticut as lieutenant governor and U.S. senator, and he was chairman of the McCarthy-era Civil Service Commission Loyalty Review Board.

His seven sons vied to impress him. Harry, the second eldest, and his brother Jonathan (who would become a Democratic congressman from New York) attended the Groton School in Massachusetts, whose illustrious alumni included Franklin D. Roosevelt. Harry had a bookish appearance but excelled at tennis, football, gymnastics and other sports.

Those who knew Harry said he spoke with animation and conviction after overcoming an initial reserve. Family members recalled that he always defended younger students from bullying upperclassmen. His brothers sometimes considered him pompous, perhaps too serious. His schoolmates called him "righteous Bingham."

Harry shared his father's wanderlust. After graduating from Yale University in 1925, he went to China as a civilian U.S. Embassy employee, attended Harvard Law School and then joined the State Department, which posted him to Japan, London (where he met Rose Morrison, a Georgia debutante, whom he soon married) and Warsaw before transferring him, at age 34, to Marseille in 1937.

Europe was careering toward war, but the first few years of Bingham's assignment seem to have been routine enough—other than a chilling visit he paid to Berlin after Hitler rose to power in 1933. In a rare reminiscence recorded by a teenage granddaughter for a school project in the 1980s, Bingham said he and Rose had been repulsed when they "had seen the broken windows where the Jewish stores had all been smashed and there were signs in the restaurants, 'No Jews or Dogs Allowed.' "

In June 1940, the Wehrmacht invaded France by land and air. Bingham sent his pregnant wife and their four children back to the United States, but he himself seemed aloof from the danger. "Two more air raids," he wrote on June 2 as he watched Luftwaffe attacks on Marseille. "Thrilling dive bombing over port...several hangars damaged and two other ships hit." Everyone at the embassy was "very excited about the raids," he noted. Then he headed off to his club for three sets of tennis, only to be disappointed when one match was "called off as my opponent did not show up."

But over the course of a week—as more bombs fell, as he read news of the Germans' overrunning of Belgium and Holland, as refugees poured into Marseille—Bingham's jottings took on a more urgent tone: "Long talk with a Belgian refugee from Brussels who told pitiful story of harrowing experiences during the last days in Brussels and flight to France," he wrote on June 7. "Noise of sirens and diving planes terrorized them...men crying Heil Hitler made human bridges for advancing troops, piles of corpses 5 feet high."

Bingham also worried that "the young Nazis [were] warped and infected with a fanaticism which may make them impossible to deal with for years." He added: "Hitler has all the virtues of the devil—courage, persistence, stamina, cunning, perseverance."

After taking Paris on June 14, 1940, Hitler divided France into an occupied zone and a state to the south that became known for its new capital, Vichy. Tens of thousands of European refugees had been corralled in squalid internment camps throughout southern France; Hitler obliged the Vichy government to hold the refugees until German intelligence units could investigate them. As more refugees streamed into southern France, thousands got as far as Marseille and hundreds lined up at the U.S. Consulate at Place Félix-Baret to beg for documents that would allow them to leave. But the de facto U.S. policy was to stall.

In Washington, James G. McDonald, head of the President's Advisory Committee on Political Refugees, supported pleas from Jewish leaders and others that the United States admit refugees in large numbers. But Breckinridge Long, an assistant secretary of state and head of the Special War Problems Division, opposed that view. Xenophobic and quite possibly anti-Semitic, Long shared a widespread if unfounded fear that German agents would be infiltrated among the visa applicants. In a 1940 memorandum, he wrote that the State Department could delay approvals "by simply advising our consuls to put every obstacle in the way...which would postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of the visas."

As a result, most American consulates in Europe interpreted immigration rules strictly. In Lisbon, "they are very reluctant to grant what they call 'political visas,' that is, visas to refugees who are in danger because of their past political activities," wrote Morris C. Troper, chairman of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, in 1940. "Pretty much the same situation prevails in the American Consulate in Marseille," he went on, "although one of the vice-consuls there, Mr. Hiram Bingham, is most liberal, sympathetic and understanding."

Bingham had, in fact, silently broken ranks. "[I] was getting as many visas as I could to as many people," he told his granddaughter—in a conversation that most family members would hear only years later. "My boss, who was the consul general at that time, said, 'The Germans are going to win the war. Why should we do anything to offend them?' And he didn't want to give any visas to these Jewish people."

The case of Lion Feuchtwanger, Bingham's first rescue operation, had come about because the first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, asked the State Department to issue him an exit visa after Feuchtwanger's editor in the United States informed her of his plight. But while staying at Bingham's villa, the novelist overheard his host arguing over the telephone with his superiors and realized that in hiding him, Bingham had acted on his own. As Bingham searched for a way to get Feuchtwanger safely out of the country, he hid him all through the summer of 1940. By August, an organization called the Emergency Rescue Committee had been established in New York City; once again Feuchtwanger benefited from Eleanor Roosevelt's patronage. In meetings with her, Rescue Committee members developed a list of prominent exiles to be helped. They then sent American journalist Varian Fry to Marseille as their representative. Fry, whose efforts to help some 2,000 refugees escape from France would eventually be well chronicled and widely honored, quickly contacted Bingham.

Bingham issued the novelist a false travel document under the name "Wetcheek," the literal translation of Feuchtwanger from the German. In mid-September 1940 "Wetcheek" and his wife, Marta, left Marseille with several other refugees; he made his way to New York City aboard the SS Excalibur. (His wife followed on a separate ship.) When Feuchtwanger disembarked on October 5, the New York Times reported that he spoke "repeatedly of unidentified American friends who seemed to turn up miraculously in various parts of France to aid him in crucial moments in his flight." (Feuchtwanger settled in the Los Angeles area, where he continued to write. He died in 1958, at the age of 74.)

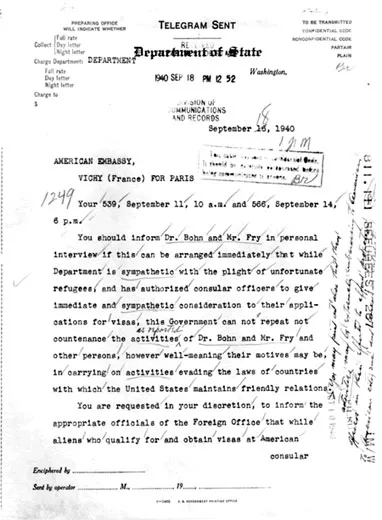

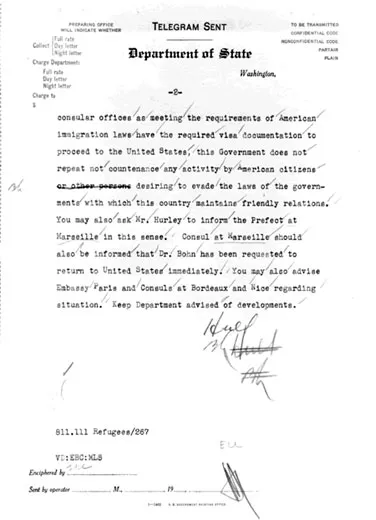

The State Department, of course, knew precisely who Feuchtwanger's American friends were. Soon after the writer left Marseille, Secretary of State Cordell Hull wired the U.S. Embassy at Vichy: "[T]his Government can not repeat not countenance the activities as reported of...Mr. Fry and other persons, however well-meaning their motives may be, in carrying on activities evading the laws of countries with which the United States maintains friendly relations."

Bingham's boss in Marseille, Consul General Hugh Fullerton, advised Fry to leave the country. Fry declined. For his part, Bingham surreptitiously broadened his work with Fry—setting him up, for example, with a police captain who was sympathetic to escape operations. The vice consul "had no hesitation to work with Fry," says Pierre Sauvage, a filmmaker who is gathering material for a documentary on Fry's work in Marseille. "If Bingham could find a way of bending the rules, of being accommodating to somebody who wanted to get out, he did that."

Through the summer of 1940, Bingham also gave secret shelter to Heinrich Mann, brother of novelist Thomas Mann; the novelist's son, Golo, also left Europe with Bingham's help. Both "have repeatedly spoken to me about your exceptional kindness and incalculable help to them in their recent need and danger," Thomas Mann wrote Bingham on October 27, 1940. "My feeling of indebtedness and gratitude to you is very great."

Bingham also visited Marc Chagall, a Jew, at Chagall's home in the Provençal village of Gordes and persuaded him to accept a visa and flee to the United States; their friendship continued for the rest of their lives. At the consulate, Bingham continued to issue visas and travel papers, which in many cases replaced confiscated passports. Fred Buch, an engineer from Austria, received an exit visa and temporary travel documents; he left Marseille with his wife and two children and settled in California. "God, it was such a relief," Buch told Sauvage in a 1997 interview. "Such a sweet voice. You felt so safe there in the consulate when he was there. You felt a new life will start." Bingham "looked like an angel, only without wings," Buch added. "The angel of liberation."

State Department files show that Bingham issued dozens of visas daily, and many other elements of his work—sheltering refugees, writing travel papers, meeting with escape groups—were not always recorded. "My father had to keep what he was doing secret, but I think people suspected it," says William Bingham. "From his perspective, what he was doing by defying the direct orders [of his own government] was complying with international law."

Bingham's next act, however, was even more provocative: with winter approaching, he began pressing for U.S. support for relief efforts at the detention camps around Marseille.

In 1940, there were about two dozen such camps in Vichy France, many of them having been originally set up in the 1930s for émigrés from Spain during the Spanish Civil War. Even before the Nazis took Paris that June, French authorities ordered European foreigners to report for internment on the ground that the criminals, spies and anti-government operatives among them had to be weeded out. From November 27 to December 1, Bingham visited camps at Gurs, Le Vernet, Argelès-sur-Mer, Agde and Les Milles, accompanied by an official who was coordinating the work of 20 international relief organizations in Marseille.

French authorities actually welcomed such relief missions, because local officials lacked the infrastructure and supplies to care for the inmates adequately. In a report Bingham wrote of his travels, he cited "immigration problems" as the reason for his trip, but his account portrays a gathering tragedy for the 46,000 camp inmates. Gurs, one of the largest camps, he wrote, held about 14,000 people, including 5,000 women and 1,000 children, and many of the detainees were diseased, malnourished or badly housed. Three hundred inmates had died there in November, 150 in the first ten days of December. "When the shortage of food becomes more acute, the camps may be used as centers of unrest," Bingham wrote. "Resulting riots may be used if desired as an excuse for intervention and military occupation of the whole of France."

When Bingham's report was forwarded to Secretary of State Hull on December 20, 1940, it was preceded by a caveat from Bingham's boss, Consul General Fullerton: "Mr. Bingham's trip to the camps was in nowise official and under instructions from the Department of State," Fullerton had written. "It was, in fact, made at his own expense."

In Washington, immigration policy remained unchanged. Later that month, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote to the State Department to ask what could be done about France's refugee crisis; she may not have seen Bingham's report, but she was still in close communication with the Emergency Rescue Committee. On January 10, Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles blamed the French: "The French government has been unwilling or has failed to grant the required exit permits with the consequence that these persons have not been able to proceed to the United States and remain on French territory where they must be cared for and fed," he wrote, then added pointedly: "I believe, despite some critics who are not aware of the facts, the machinery we have set up to deal with the emergency refugee problem is functioning effectively and well."

But Bingham, despite the State Department's reluctance, continued to work with relief organizations outside the government. With his help, Martha Sharp of the Unitarian Service Committee and others assembled 32 refugees, including 25 children, and got them onto a ship that arrived in New York, on December 23.

Robert C. Dexter, a director of the Boston-based committee, wrote to Hull to commend "the sympathetic and understanding way in which Vice-Consul Hiram Bingham, Jr. carried out his responsibilities at the consulate....Mrs. Sharp reports that his whole conduct made other Americans proud of the way he represents their government to foreigners coming before him for assistance."

Breckinridge Long, the assistant secretary of state who had been adamant about closing the gates to immigrants, replied that "the Department is always glad to learn that its officers abroad are proving themselves of service to American citizens and their interests." Long's tepid response reflected growing concern among Bingham's superiors about his activities. "In general, Bingham was stretching the boundaries," says historian Richard Breitman, who has written extensively on the period. "Bingham was on one side, and Long and the majority of consuls were on the other side."

In the winter of 1941, one of Bingham's Marseille superiors, William L. Peck, wrote a memo describing Peck's efforts to give humanitarian consideration "to aged people, especially those in the camps. These are the real sufferers and the ones who are dying off." He then added: "The young ones may be suffering, but the history of their race shows that suffering does not kill many of them. Furthermore, the old people will not reproduce and can do our country no harm, provided there is adequate evidence of support." Such an expression of anti-Semitism within the government, which was forwarded to the secretary of state, as well as to the consulates in Lyon and Nice, was not unusual during the war, Breitman says; overt anti-Semitism did not recede until the Nazi concentration camps were liberated in 1945 and the true dimensions of the Holocaust began to emerge.

Although Bingham left no record that he sensed any trouble, his time in Marseille was running out. In March 1941, Long effectively silenced McDonald's pleas for a more open immigration policy; in official Washington sentiment for aiding refugees evaporated.

In April, Bingham was delegated to accompany the new U.S. ambassador to Vichy, retired Adm. William D. Leahy, during Leahy's official visit to Marseille. Nothing gave any indication of tensions, and afterward Bingham sent a note to the ambassador saying, "It was a great privilege for me to have had the opportunity of being with you and Mrs. Leahy during your short visit here."

A few days later, a wire from Washington arrived in Marseille: "Hiram Bingham, Jr., Class VIII, $3600, Marseille has been assigned Vice Consul at Lisbon and directed proceed as soon as practicable....This transfer not made at his request nor for his convenience."

There is no explanation in official records for the transfer, though notes found among Bingham's papers suggest the reasons: "Why was I transferred to Lisbon," he wrote. "Attitude toward Jews—me in visa section...attitude toward Fry." In any case, on September 4, while Bingham was on home leave, he received another telegram from the State Department: "You are assigned Vice Consul at Buenos Aires and you should proceed upon the termination of your leave of absence."

Bingham was in Buenos Aires when the United States entered World War II. He spent the remainder of the war there in the rank of vice consul and was an ongoing irritant to the State Department with his complaints about Nazis who had slipped out of Europe. They were operating openly in nominally neutral Argentina, whose military government dominated by Col. Juan Domingo Perón hardly disguised its fascist sympathies. "Perón and his whole gang are completely unreliable, and, whatever happens, all countries in South America will be seedbeds of Nazism after the war," Bingham wrote in a confidential memo to his superiors.

When, after the war, Bingham's request to be posted to Nazi-hunting operations in Washington, D.C. was turned down, he resigned from the Foreign Service and returned to the family farm in Connecticut. "For the children it was wonderful. Daddy was always there," says his daughter Abigail Bingham Endicott, 63, a singer and voice teacher in Washington, D.C. "He spent part of the day playing with the kids and much time in his study, dreaming up new business ideas." He designed a device called the Sportatron, an enclosed court 12 feet by 24 feet with various attachments and adjustments that would allow the user to play handball, tennis, basketball, even baseball in confined spaces. "Unfortunately, he didn't master the skill of selling and promoting something on a big scale," says Abigail. After a while, she says, he lost his patent on the device.

Bingham went through his inheritance. Wanting to live off the land as well as to save money, he bought a cow and chickens. Rose became a substitute teacher. "I was pretty much dressed in hand-me-downs," says William Bingham. His father "tried to fix things around the house, but wasn't good at it."

Amid Harry's financial hardship, his father, who lived in Washington, set up a trust fund to educate Harry's children. Abigail recalls a rare visit from the famous old explorer. "He was wearing a white linen suit and made us line up in order of age," she says. "There were maybe eight or nine of us, and he handed each of us a freshly minted silver dollar."

In his later years, says Abigail, Harry Bingham "told my older sister that he was very sorry he couldn't have left money for the family, but that he was very poor." ("Oh, Daddy, you've given us each other," she replied.) After his widow, Rose, died, the house passed into a trust that allows the Bingham children and others to use it, which is how William came to discover the documents his father had left behind.

William's discovery helped satisfy a curiosity that had been intensifying ever since the Bingham family was invited, in 1993, to a tribute to Varian Fry and other rescuers, sponsored by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. In 1996, William brought the documents he had found to the museum, where a curator expressed interest in including information about Harry in future exhibits. In 1998, the Yad Vashem Memorial in Jerusalem honored Bingham and ten other diplomats for having saved some 200,000 lives during the war.

Robert Kim Bingham, 66, Harry's sixth child, who went to Jerusalem for the Yad Vashem ceremonies, marshaled a campaign for recognition of his father in his own country; in June 2002, Bingham's "constructive dissent" was recognized when he was designated a Courageous Diplomat by the American Foreign Service Association, the society of Foreign Service professionals, at the State Department. Bingham, said Secretary of State Colin L. Powell, had "risked his life and his career, put it on the line, to help over 2,500 Jews and others who were on Nazi death lists to leave France for America in 1940 and 1941. Harry was prepared to take that risk to his career to do that which he knew was right."

Afterward, the department revised Bingham's biographical entry in its official history, highlighting his humanitarian service. In 2006, the Postal Service released a stamp bearing Bingham's likeness.

As Harry Bingham's story spread, a few dozen of the people he had helped and their survivors came forward, writing to his children, filling in the portrait of their father. "He saved my Mother, my sister and I," Elly Sherman, whose family eventually settled in Los Angeles, wrote to Robert Kim Bingham. She included a copy of a visa bearing Harry's signature and dated May 3, 1941—ten days before he left Marseille. "Without him we would not have been able to avoid the concentration camp to which we were assigned two days later."

Abigail Bingham Endicott says she wishes her father knew how proud his children are of him. "We had no idea about the extent of what he had done," she says. She recalls a hymn the family often sang at gatherings and in it she hears a suggestion of her father's predicament in Marseille:

Once to every man and nation, comes the moment to decide,

In the strife of truth with falsehood, for the good or evil side;

Some great cause, some great decision,

offering each the bloom or blight,

And the choice goes by forever,

'twixt that darkness and that light.

Peter Eisner has written three books, including The Freedom Line, about the rescue of Allied airmen shot down over Europe.