Rehabilitating Cleopatra

Egypt’s ruler was more than the sum of the seductions that loom so large in history—and in Hollywood

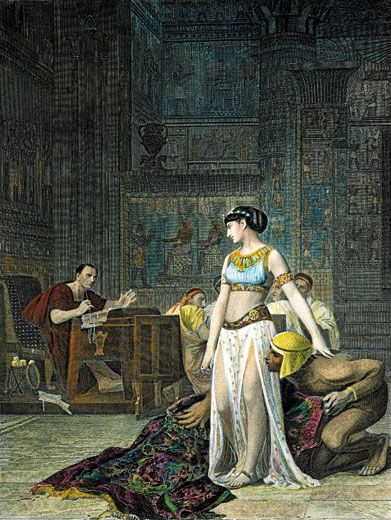

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Presence-Cleopatra-engraving-631.jpg)

Cleopatra VII ruled Egypt for 21 years a generation before the birth of Christ. She lost her kingdom once; regained it; nearly lost it again; amassed an empire; lost it all. A goddess as a child, a queen at 18, at the height of her power she controlled virtually the entire eastern Mediterranean coast, the last great kingdom of any Egyptian ruler. For a fleeting moment she held the fate of the Western world in her hands. She had a child with a married man, three more with another. She died at 39. Catastrophe reliably cements a reputation, and Cleopatra's end was sudden and sensational. In one of the busiest afterlives in history, she has become an asteroid, a video game, a cigarette, a slot machine, a strip club, a synonym for Elizabeth Taylor. Shakespeare attested to Cleopatra's infinite variety. He had no idea.

If the name is indelible, the image is blurry. She may be one of the most recognizable figures in history, but we have little idea what Cleopatra actually looked like. Only her coin portraits—issued in her lifetime, and which she likely approved—can be accepted as authentic. We remember her, too, for the wrong reasons. A capable, clear-eyed sovereign, she knew how to build a fleet, suppress an insurrection, control a currency. One of Mark Antony's most trusted generals vouched for her political acumen. Even at a time when female rulers were no rarity, Cleopatra stood out, the sole woman of her world to rule alone. She was incomparably richer than anyone else in the Mediterranean. And she enjoyed greater prestige than every other woman of her time, as an excitable rival king was reminded when he called for her assassination during her stay at his court. (The king's advisers demurred. In light of her stature, they reminded Herod, it could not be done.) Cleopatra descended from a long line of murderers and upheld the family tradition, but was for her time and place remarkably well behaved.

She nonetheless survives as a wanton temptress, not the first time a genuinely powerful woman has been transmuted into a shamelessly seductive one. She elicited scorn and envy in equal and equally distorting measure; her story is constructed as much of male fear as of fantasy. Her power was immediately misrepresented because—for one man's historical purposes—she needed to have reduced another to abject slavery. Ultimately everyone from Michelangelo to Brecht got a crack at her. The Renaissance was obsessed with her, the Romantics even more so.

Like all lives that lend themselves to poetry, Cleopatra's was one of dislocations and disappointments. She grew up amid unsurpassed luxury and inherited a kingdom in decline. For ten generations her family, the Ptolemies, had styled themselves pharaohs. They were in fact Macedonian Greek, which makes Cleopatra about as Egyptian as Elizabeth Taylor. She and her 10-year-old brother assumed control of a country with a weighty past and a wobbly future. The pyramids, to which Cleopatra almost certainly introduced Julius Caesar, already sported graffiti. The Sphinx had undergone a major restoration—more than 1,000 years earlier. And the glory of the once-great Ptolemaic empire had dimmed. Over the course of Cleopatra's childhood Rome extended its rule nearly to Egypt's borders. The implications for the last great kingdom in that sphere of influence were clear. Its ruler had no choice but to court the most powerful Roman of the day—a bewildering assignment in the late Republic, wracked as it was by civil wars.

Cleopatra's father had thrown in his lot with Pompey the Great. Good fortune seemed eternally to shine on that brilliant Roman general, at least until Julius Caesar dealt him a crushing defeat in central Greece. Pompey fled to Egypt, where in 48 B.C. he was stabbed and decapitated. Twenty-one-year-old Cleopatra was at the time a fugitive in the Sinai—on the losing side of a civil war against her brother and at the mercy of his troops and advisers. Quickly she managed to ingratiate herself with the new master of the Roman world.

Julius Caesar arrived in Alexandria days after Pompey's murder. He barricaded himself in the Ptolemies' palace, the home from which Cleopatra had been exiled. From the desert she engineered a clandestine return, skirting enemy lines and Roman barricades, arriving after dark inside a sturdy sack. Over the succeeding months she stood at Caesar's side—pregnant with his child—while he battled her brother's troops. With their defeat, Caesar restored her to the throne.

For the next 18 years Cleopatra governed the most fertile country in the Mediterranean, guiding it through plague and famine. Her tenure alone speaks to her guile. She knew she could be removed at any time by Rome, deposed by her subjects, undermined by her advisers—or stabbed, poisoned and dismembered by her own family. In possession of a first-rate education, she played to two constituencies: the Greek elite, who initially viewed her with disfavor, and the native Egyptians, to whom she was a divinity and a pharaoh. She had her hands full. Not only did she command an army and navy, negotiate with foreign powers and preside over temples, she also dispensed justice and regulated an economy. Like Isis, one of the most popular deities of the day, Cleopatra was seen as the beneficent guardian of her subjects. Her reign is notable for the absence of revolts in the Egyptian countryside, quieter than it had been for a century and a half.

Meanwhile the Roman civil wars raged on, as tempers flared between Mark Antony, Caesar's protégé, and Octavian, Caesar's adopted son. Repeatedly the two men divided the Roman world between them. Cleopatra ultimately allied herself with Antony, with whom she had three children; together the two appeared to lay out plans for an eastern Roman empire. Antony and Octavian's fragile peace came to an end in 31 B.C., when Octavian declared war—on Cleopatra. He knew Antony would not abandon the Egyptian queen. He knew too that a foreign menace would rouse a Roman public that had long lost its taste for civil war. The two sides ultimately faced off at Actium, a battle less impressive as a military engagement than for its political ramifications. Octavian prevailed. Cleopatra and Antony retreated to Alexandria. After prolonged negotiation, Antony's troops defected to Octavian.

A year later Octavian marched an army to Egypt to extend his rule, claim his spoils and transport the villain of the piece back to Rome, as a prisoner. Soundly defeated, Cleopatra could negotiate only the form of her surrender. She barricaded herself in a vast seaside mausoleum. The career that had begun with a brazen act of defiance ended with another; for the second time she slipped through a set of enemy fingers. Rather than deliver herself to Octavian, she committed suicide. Very likely she enlisted a gentle poison rather than an asp. Octavian was at once disappointed and in awe of his enemy's "lofty spirit." Cleopatra's was an honorable death, a dignified death, an exemplary death. She had presided over it herself, proud and unbroken to the end. By the Roman definition she had at last done something right; finally it was to Cleopatra's credit that she had defied the expectations of her sex. With her death the Roman civil wars came to an end. So too did the Ptolemaic dynasty. In 30 B.C. Egypt became a province of Rome. It would not recover its autonomy until the 20th century A.D.

Can anything good be said of a woman who slept with the two most powerful men of her time? Possibly, but not in an age when Rome controlled the narrative. Cleopatra stood at one of the most dangerous intersections in history: that of women and power. Clever women, Euripides had warned 400 years earlier, were dangerous. We do not know whether Cleopatra loved either Antony or Caesar, but we do know that she got them to do her bidding. From the Roman point of view, she "enslaved" them both. Already it was a zero-sum game: a woman's authority spelled a man's deception.

To a Roman, Cleopatra was thrice suspect, once for hailing from a culture known—as Cicero had it—for its "fribbling, fawning ways," again for her Alexandrian address, lastly for her staggering wealth. A Roman could not pry apart the exotic and the erotic; Cleopatra was a stand-in for the occult, alchemical East, for her sinuous, sensuous land, as perverse and original as its astonishment of a river. Men who came in contact with her seem to have lost their heads, or at least to have rethought their agendas. The siren call of the East long predated her, but no matter: she hailed from the intoxicating land of sex and excess. It is not difficult to understand why Caesar became history, Cleopatra a legend.

Her story differs from most women's stories in that the men who shaped it enlarged rather than erased her role, for their own reasons. Her relationship with Antony was the longest of her life—the two were together for the better part of 11 years—but her relationship with Octavian proved the most enduring. He made much of his defeat of Antony and Cleopatra, delivering to Rome the tabloid version of an Egyptian queen, insatiable, treacherous, bloodthirsty, power-crazed. Octavian magnified Cleopatra to hyperbolic proportions to do the same with his victory—and to smuggle Mark Antony, his real enemy and former brother-in-law, out of the picture.

As Antony was erased from the record, Actium was wondrously transformed into a major engagement, a resounding victory, a historical turning point. Octavian had rescued Rome from great peril. He had resolved the civil war; he had restored peace after 100 years of unrest. Time began anew. To read the official historians, it is as if with his return the Italian peninsula burst—after a crippling, ashen century of violence—into Technicolor, the crops sitting suddenly upright, crisp and plump, in the fields. "Validity was restored to the laws, authority to the courts, and dignity to the senate," proclaims the historian Velleius.

The years after Actium were a time of extravagant praise and lavish mythmaking. Cleopatra was particularly ill-served; the turncoats wrote the history. Her career coincided as well with a flowering of Latin literature. It was Cleopatra's curse to inspire its great poets, happy to expound on her shame, in a language inhospitable to her. Horace celebrated her defeat before it had occurred. She helpfully illuminated one of the poet Propertius's favorite points: a man in love is a helpless man, painfully subservient to his mistress. It was as if Octavian had delivered Rome from that ill as well. He restored the natural order of things. Men ruled women, and Rome ruled the world. On both counts Cleopatra was crucial to the story. She stands among the few losers whom history remembers, if for the wrong reasons. For the next century, the Oriental influence and the emancipation of women would keep the satirists in business.

Propertius set the tone, dubbing Cleopatra "the whore queen." She would later become "a woman of insatiable sexuality and insatiable avarice" (Dio), "the whore of the eastern kings" (Boccaccio). She was a carnal sinner for Dante, for Dryden a poster child for unlawful love. A first-century A.D. Roman would falsely assert that "ancient writers repeatedly speak of Cleopatra's insatiable libido." Florence Nightingale referred to her as "that disgusting Cleopatra." Offering Claudette Colbert the title role in the 1934 movie, Cecile B. DeMille is said to have asked, "How would you like to be the wickedest woman in history?"

Inevitably affairs of state have fallen away, leaving us with affairs of the heart. We will remember that Cleopatra slept with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony long after we remember what she accomplished in doing so: that she sustained a vast, rich, densely populated empire in its troubled twilight. A commanding woman versed in politics, diplomacy and governance, fluent in nine languages, silver-tongued and charismatic, she has dissolved into a joint creation of the Roman propagandists and the Hollywood directors. She endures for having seduced two of the greatest men of her time, while her crime was in fact to have entered into the same partnerships that every man in power enjoyed. That she did so in reverse and in her own name made her deviant, socially disruptive, an unnatural woman. She is left to put a vintage label on something we have always known existed: potent female sexuality.

It has forever been preferable to attribute a woman's success to her beauty rather than to her brains, to reduce her to the sum of her sex life. Against a powerful enchantress there is no contest. Against a woman who ensnares a man in the coils of her serpentine intelligence—in her ropes of pearls—there should, at least, be some kind of antidote. Cleopatra would unsettle more as sage than as seductress; it is less threatening to believe her fatally attractive than fatally intelligent. As one of Caesar's murderers noted, "How much more attention people pay to their fears than to their memories!"

A center of intellectual jousting and philosophical marathons, Alexandria remained a vital center of the Mediterranean for a few centuries after Cleopatra's death. Then it began to dematerialize. With it went Egypt's unusual legal autonomy for women; the days of suing your father-in-law for the return of your dowry when your husband ran off with another woman were over. After a fifth-century A.D. earthquake, Cleopatra's palace slid into the Mediterranean. Alexandria's magnificent lighthouse, library and museum are all gone. The city has sunk some 20 feet. Ptolemaic culture evaporated as well; much of what Cleopatra knew would be neglected for 1,500 years. Even the Nile has changed course. A very different kind of woman, the Virgin Mary, would subsume Isis as entirely as Elizabeth Taylor has subsumed Cleopatra. Our fascination with the last queen of Egypt has only increased as a result; she is all the more mythic for her disappearance. The holes in the story keep us coming back for more.

Adapted from Cleopatra: A Biography, by Stacy Schiff. Copyright © 2010. With permission of Little, Brown and Company. All rights reserved.

Stacy Schiff won the Pulitzer Prize for her 1999 biography, Véra (Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov): Portrait of a Marriage.