The True Story of Misty of Chincoteague, the Pony Who Stared Down a Devastating Nor’Easter

The Ash Wednesday Storm of 1962 was a horse of another color

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/13/9a13ee09-ce25-45c2-8ce9-69962f7d75c2/ap_02072403180.jpg)

Assateague and Chincoteague's most famous residents know how to stay safe in extreme weather conditions. After all, the wild ponies have comfortably roamed the islands along the mid-Atlantic coast for centuries. While legend says they arrived at the barrier islands of Virginia and Maryland after surviving a shipwreck, it’s more likely that their origin can be traced to horses owned by 17th-century settlers.

However they arrived, these feral herds have thrived over the years, no matter the obstacle, and have become a permanent fixture of the region’s character. So, when Hurricane Florence threatened the Atlantic coast earlier this fall, officials were unconcerned with their safety. "This is not their first rodeo," Kelly Taylor, supervisor of the Maryland District Division of Interpretation and Education, told the media. "They come from a hearty stock, and they can take care of themselves."

But the Ash Wednesday Storm of 1962 was a different story. The Level 5 nor'easter was fierce and unrelenting in its three-day barrage. Poultry farms flooded, houses disappeared underwater, and coffins floated. For thousands of American children paying attention to the news, one question about the crisis rose above the rest: Was Misty all right?

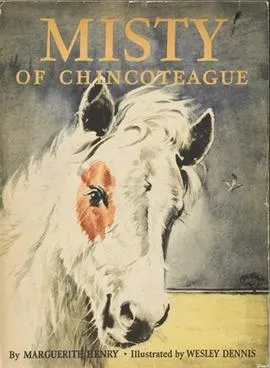

Misty of Chincoteague, a 16-year-old palomino mare, was the best-known member of the herd of wild ponies. She catapulted to fame 14 years earlier, when children’s book author Marguerite Henry wrote Misty of Chincoteague. The book tells the story of orphans Paul and Maureen Beebe, who long to buy a mare named Phantom and her filly Misty and bring them to their grandparents’ farm.

Henry, a Newbery-award winning author, wrote 59 books, many of them about horses. She wrote about the burros who carry loads in the Grand Canyon, 1924 Kentucky Derby winner Black Gold, and the Godolphin Arabian. But Misty had a special kind of alchemy for readers, perhaps because Paul and Maureen lived the dream of every horse-crazy kid: surrounded by ponies and pining for one of their own, they wind up with her. "Misty here, she belongs to us," their grandfather tells them. The book centers on the themes of freedom and belonging: the animal lover's twofold fantasy.

Henry traveled to Chincoteague in 1945, looking to write a book about the ponies. There she visited Beebe Ranch, which was home to the real-life foal Misty.* The pony captivated her, and in 1946, she arranged to have Misty shipped to her home in Wayne, Illinois. When the book became a bestseller, Misty became an overnight celebrity, named an honorary member of the American Library Association, and invited to attend its annual convention at the Pantlind Hotel in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

At her home in Illinois, Henry hosted many visitors who pilgrimaged to see Misty. "If a troop of Scouts or Bluebirds arrived on a pouring-down, drenching day," wrote Henry in her non-fiction account A Pictorial Life Story of Misty, "we brought Misty into the house where she shook hands all around and posed obligingly for all the Brownie cameras that came out of pockets and bags."

In 1957, Henry returned Misty to her native islands so she could bear foals. But Misty didn’t stay totally out of the limelight; when the film adaptation Misty came out four years later, she reemerged to the public for the premiere. Locals paraded her through Chincoteague and had her hoofprints imprinted in cement, in front of the town’s main theater.

When the Ash Wednesday storm struck on the first day of Lent in 1962, Misty was pregnant and back at the Beebe ranch. With the water unsafe to drink and the island in turmoil, human residents were evacuated to nearby Wallops Island.

Misty weathered the storm in the family's kitchen. A cat kept her company, and she made herself at home there, lapping up some spilled molasses. "And there," Ralph Beebe, who had inherited the ranch from his parents, Clarence and Ida, assured the public, "is where she's going to stay."

Still, fans worried about the beloved pony. Their fears were magnified when they learned Misty was pregnant. Officials on the Eastern Shore told the Associated Press that their phones had been ringing off the hook with calls about Misty. Often, a child's voice was on the end of the line, asking if Misty was all right. "Misty of Chincoteague Reported Safe," ran one in the Washington Post. "Relax, Kids, Misty's OK," said a Pennsylvania paper.

While Misty made it through the storm, not all the ponies came out so lucky. Of the 300 living on both islands, 55 died on Assateague and 90 on Chincoteague. Many drowned, carried out to sea.

Meanwhile, Misty was ready to foal. Ralph Beebe took her to the veterinarian on mainland Virginia. There she gave birth to a delicate and sprightly filly with wide, bright eyes and a chestnut and white coat.

As Misty had just made national headlines for surviving the storm, people around the country were eager for news of her foal. The Beebes received hundreds of letters—including one from every single member of the second grade in a Reisterstown, Maryland, school—with suggestions for the newborn foal’s name. The Beebes were persuaded by one that addressed the natural disaster Misty had just lived through. Though exact accounts of the letter that convinced the Beebes differed, in an article in the Chicago Tribune, Henry recounted the letter went something like this: "I think you were wonderful to bring Misty into your kitchen," she recalls. "Why can't you name the baby Stormy because of the tidal wave?"

The happy news of the foal brought a welcome relief to the devastating aftermath of the storm. Back on the islands, helicopters lifted dead ponies by rope, placed then in trucks, which then moved them to the mainland for burial. Many were newborn colts, or mares that had been ready to foal. The loss of the ponies was not only tragic, but a large threat to the local economy. Without them, there would be no “pony penning,” the annual event that brings tourists to Chincoteague in the summer. During the penning, volunteers on horseback—"saltwater cowboys"—round up ponies, which are then swum across the water from Assateague to Chincoteague and sold at auction. As Henry described it in Misty: "Onlookers fell back while Maureen, Grandpa Beebe, and the other horsemen surrounded the ponies and began driving them toward town. The Phantom broke at the start, her colt weaving along behind her like the tail of a kite." Funds benefit the fire department, and the annual sale still goes on today.

Misty, in her own way, came to the rescue. Twentieth Century Fox re-released its film into theaters as a fundraiser for the “Misty Disaster Fund.” Proceeds restocked the pony herd, buying back ponies sold in the past. "Misty, the Chincoteague pony of book and film fame, has been cast in a leading role to replenish the island's pony herd" wrote an AP reporter.

"You might call Misty's film a horse of a different Red Cross color," joked Chincoteague's mayor, Robert Reed.

To drum up attention for the charity drive, Misty and newborn Stormy made appearances in theaters across Maryland and Virginia. In Salisbury, Maryland, the crowds were so big at the first showing that the ponies stayed over for a second showing. Henry and Wesley Dennis, the illustrator of Misty, made some appearances, too. Henry described the scene at Richmond's Byrd Theater when Misty and Stormy showed up: "Every eye was riveted on the two creatures tittuping down the aisle—one so sure-footed and motherly, one so lithe and wobbly. From a thousand throats came the whispered cry, 'There they are!' And the murmuring grew in power like water from a dike giving way."

The publicity tour worked. By April, Chincoteague pony owners were offering to sell their ponies back to the herd to help rebuild its numbers in the wake of the tragedy, Ralph Beebe told reporters. And in July, the pony penning would go on as always.

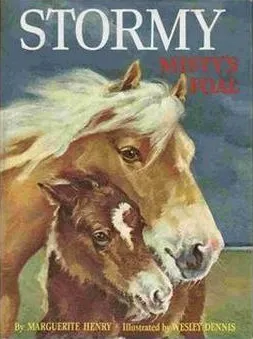

The next year, Henry's released a new novel. "My sequel had been born of violence," wrote Henry, "the violence of wind and tide; and of courage, the courage of the Beebe family who risked their own safety and took Misty into their kitchen." The title for the book was ready-made. It was called Stormy, Misty's Foal. "

*Editor's note, October 25, 2018: This story incorrectly stated that the children at the center of the Misty story were fictional. They existed in real-life, too. The story has since been corrected.