What a Simple Pen Reminds Us About Ulysses S. Grant’s Vision for a Post-Civil War America

President Grant’s signature on the 15th Amendment was a bold stroke for equality

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/8f/618f6e0c-dd8b-4b0a-b08b-74235dd750ea/nov2017_c02_prologue.jpg)

President Ulysses S. Grant placed a high priority on the welfare of black citizens, to whom he offered unprecedented White House access. On December 11, 1869, he received a delegation from the National Labor Convention, the predominantly black group of union organizers. While he couldn’t gratify all their wishes, especially their desire to redistribute land to black laborers in the South, he left no doubt of his extreme solicitude for their concerns. “I have done all I could to advance the best interests of the citizens of our country, without regard to color,” he told them, “and I shall endeavor to do in the future what I have done in the past.”

Grant made good on his promise when he designated November 30 of that year as the date for Mississippi and Texas to vote on new state constitutions that would guarantee voting rights for black males and readmit the two states to the Union.

When Mississippi’s new, heavily Republican legislature gathered in January 1870, it signaled a radical shift in Southern politics in its selection of two new senators. One was Adelbert Ames and the other Hiram Revels, a minister who became the first black person to serve in the U.S. Senate. In a powerful piece of symbolism, Revels occupied the Senate seat once held by Jefferson Davis.

The 15th Amendment prevented states from denying voting rights based on race, color or earlier condition of servitude. For Grant this amendment embodied the logical culmination of everything he had fought for during the war. In the words of Adam Badeau, an Army officer who had served on the general’s wartime staff and later became Grant’s biographer, the president thought that “in order to secure the Union which he desired and which the Northern people had fought for, a voting population at the South friendly to the Union was indispensable.”

On February 3, the 15th Amendment was ratified and its acceptance required for every Southern state readmitted to the Union. The pen used by Grant to sign the ratification proclamation that day now resides in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

On March 30, as 100 guns boomed in the capital in celebration, Grant composed an unusual message to Congress celebrating that the amendment had become part of the Constitution that day, and his words fervently embraced black suffrage: “The adoption of the 15th Amendment . . . constitutes the most important event that has occurred, since the nation came into life.”

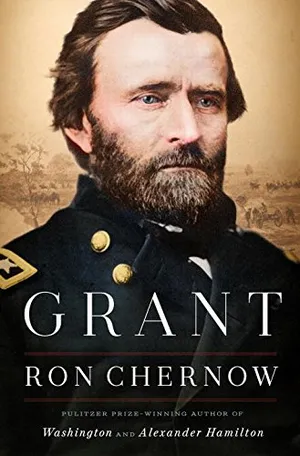

Grant

The definitive biography, Grant is a grand synthesis of painstaking research and literary brilliance that makes sense of all sides of Grant's life, explaining how this simple Midwesterner could at once be so ordinary and so.

That evening, to commemorate the landmark amendment, thousands marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in a torchlight procession. When they gathered outside the White House, Grant came out to address them, saying there had been “no event since the close of the war in which I have felt so deep an interest....It looked to me as the realization of the Declaration of Independence.”

Grant’s brother‑in‑law Michael John Cramer later explained that Grant had initially worried about bestowing voting rights upon black citizens, some of them still illiterate. Ku Klux Klan terror wiped away that hesitation, for as the Klan “endeavored to suppress the political rights of the freedmen of the South by the use of unscrupulous means, etc., he, as the head of the army, became convinced...that the ballot was the only real means the freedmen had for defending their lives, property, and rights.”

Black gains can be overstated and certainly were by an alarmed white community: Fewer than 20 percent of state political offices in the South were held by blacks at the height of Reconstruction. Still, these represented spectacular gains.

Not surprisingly, the 15th Amendment incited a violent backlash among whites whose nerves were already frayed by having lost the war and their valuable holdings of human property.

Hardly had the ink dried on the new amendment than Southern demagogues began to pander to the anxieties it aroused. In West Virginia, an overwhelmingly white state, Democratic politicians sounded the battle cry of electing a “white man’s government” to gain control of the governorship and state legislature. White politicians in Georgia devised new methods of stripping blacks of voting rights, including poll taxes, onerous registration requirements and similar restrictions copied in other states.

Behind the amendment’s idealism lay the stark reality that a “solid South” of white voters would vote en masse for the Democratic Party, forcing Republicans to create a countervailing political force. Under the original Constitution, slaveholding states had been entitled to count three of every five slaves as part of their electorate in computing their share of congressional delegates. Now, after earlier passage of the 14th Amendment as well, former slaves would count as full citizens, swelling the electoral tally for Southern states. This was fine as long as freed people exercised their full voting rights.

Instead, over time, the white South would receive extra delegates in Congress and electoral votes in presidential races while stifling black voting power. “It was unjust to the North,” Grant subsequently lamented. “In giving the South negro suffrage, we have given the old slave-holders forty votes in the electoral college. They keep those votes, but disfranchise the negroes. That is one of the gravest mistakes in the policy of reconstruction.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.