It has been 20 years since four jetliners hijacked by terrorists crashed into the Twin Towers, the Pentagon and a field in Pennsylvania. The attacks killed nearly 3,000 people. To honor their memory, we worked with photographer Jackie Molloy to create portraits of several female first responders and others who were on the scene, as well as women, men and now-grown children who lost a loved one. We also asked a number of them what they remember about that September day, and we learned how it continues to shape their lives, in unique and profound ways, after two decades.

Forces Beyond

Theresa Tobin | Former lieutenant in the NYPD’s public information office

My family always upheld public service. Four of the five of us kids went into law enforcement, and the sister who didn’t married into it. From the earliest age, I knew this job was about helping people. It’s not the cops and robbers you see on TV. The bulk of our calls are from people who need help—people who are in crisis, people who are crime victims. A lot of the job is about being a calming presence, helping people navigate difficult situations. That was what made me come home feeling good at the end of the day.

When 9/11 happened, I was working at the NYPD press office. We’d gotten a call telling us that a plane had flown into the North Tower. As we drove over, there were all these sheets of paper floating above FDR Drive. I was expecting to see a small Cessna hanging off the side of the building. A few minutes after I arrived, the second plane hit the South Tower. There was a deafening roar as the plane flew low overhead. Then there was a huge fireball and glass crashed down, popping out of the building from the heat.

I crossed paths with Joe Dunne, the first deputy commissioner of the NYPD, who told me to get onto an emergency service truck and grab a Kevlar helmet. Debris was falling everywhere and I had to go into the buildings to coordinate the press response overhead.

It was remarkably calm inside the lobby of the North Tower. People were evacuating as police officers directed them: “To your left. To your left.” So, I made my way over to the South Tower and saw a news photographer snapping photos. Leading him out so he wouldn’t slow down the evacuation, I said, “Just walk backwards but keep clicking. I know you have a job to do.”

All this time, I was wearing my civilian clothes and was wearing loafers, but I realized it was going to be a long day. So I went to my car to grab my sneakers. I’d gotten close enough to my car to pop the trunk with the remote when the rumbling started. I wondered, “Where’s that train coming from?” But there was no elevated train in Lower Manhattan. Before I could reach my car, people were running toward me, screaming, “Go! It’s coming down!”

A massive force suddenly lifted me out of my shoes. I was completely helpless, like a leaf blowing in the wind. Firetrucks were moving around in the air like they were children’s toys.

I was thrown over a concrete barrier onto a grassy area outside the World Financial Center. I could feel with my hand that blood was trickling down the back of my neck. There was a chunk of cement wedged into my skull. My Kevlar helmet had taken the brunt of the force and saved my life, but the helmet had split in two.

The day turned pitch-black. People were screaming as we were buried under debris from the tower. A firefighter with a flashing beacon was close by and said, “Pull up your shirt. Just cover your mouth.” There were explosions going off. Big gas tanks were bursting into flames. It felt like we were being bombed—but who was bombing us? There was no context for what was happening. The sound distortion made it hard to figure out where people were.

After I got myself free, I heard people coughing and throwing up. I spat out what I thought was a chunk of cement but it was one of my wisdom teeth. A firefighter saw me and called out, “EMS, she has cement in her head!” The medical workers didn’t want to risk pulling at it, so they bandaged me up with the piece still lodged in my skull.

My car was in flames. So were a firetruck and an ambulance nearby. There were abandoned radios on the ground belonging to police officers and firefighters, but when I picked each one up and tried it, there was no response. Meanwhile, people around me were still screaming for help. You don’t walk away from those situations, you just ask yourself, “Where is that voice coming from and how can I get that person out?” Just about everyone we helped free from the debris or pull out from under a truck was a rescue worker in a blue or black uniform.

Moments later, another group of people were running toward me, shouting, “The North Tower is coming down!” I thought if I could make it to the water, I could jump in and the surface would take most of the impact. But something whacked me hard on my back. I fell down and knew I wouldn’t be able to reach the water in time.

I made it into a nearby apartment building. At first it seemed like there was no one inside, but when I opened the door to the stairwell, I saw a line of people. Some of them looked like they’d just come out of the shower. There was a baby crying in its mother’s arms.

I said, “All right, get into the lobby and stay away from glass.” I went to the door and through the falling ash I saw two guys from our Technical Assistance Response Unit. I called out, “These people need to be evacuated!”

A police detective saw me and said, “Listen, you’ve got to get medical attention. You have a plate of glass sticking out between your shoulder blades.” There was so much adrenaline flowing through my body that I hadn’t even been aware of it. When I got down to the pier to evacuate to Ellis Island, I heard someone say, “EMS, we have an injured officer.” I remember thinking, “Where’s the injured officer?”

The emergency workers were wonderful. From Ellis Island, they transported me to a hospital in New Jersey. I wasn’t able to lie down on a stretcher, so they loaded another person in an ambulance next to me. His name was David Handschuh, a photographer with the Daily News. He’d taken a photo of the fireball exploding on the side of the South Tower before he was lifted into the air, like I had been, and buried in debris. He was really concerned about letting his family know he was still alive, so I asked the EMS technician for a pen and wrote down David’s home phone number on the wristband they’d given me. The ambulance ride was bumpy and he winced every time we got jostled. I held his hand and told him to squeeze mine every time he felt pain.

From the emergency room, I went straight into surgery where the cement was removed and my back was stitched up. Because I’d suffered a severe concussion, they weren’t able to give me any anesthesia. My ankle was swollen, but my skin was so full of lacerations that they weren’t able to put a cast on it.

My brother Kevin, an NYPD detective, had somehow tracked me down and he met me in the recovery room. He drove me back to headquarters, where I spent a few more hours working before my condition got worse. Several of us went to a hospital on Long Island for treatment. Then Kevin drove me to my sister’s house, and I stayed there for several weeks until I recovered and could work again.

We lost 23 NYPD officers that day and 37 Port Authority police officers, including three women: Port Authority Captain Kathy Mazza, EMT Yamel Merino and NYPD Officer Moira Smith. We lost 343 firefighters. I often think about my cousin Robert Linnane from Ladder 20 who died—he was rushing up through the North Tower to help people when it collapsed. There just doesn’t seem to be any rhyme or reason about who made it and who didn’t. You made a left and you lived; you made a right and you died.

I’ve had a lot of different jobs in the years since then. I’ve been promoted up the ranks, and been the commanding officer of three different units. Now, I’m the Chief of Interagency Operations, where my role is to work with other agencies, creating programs that improve our public safety responses and give people better access to services—especially in the areas of mental health, homelessness and substance misuse. One program my office developed is our co-response unit, which teams up NYPD officers with trained clinicians from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene so we can address issues before they reach a crisis point.

I’ve never had another experience like 9/11. It’s extremely unusual for police officers to be at a scene and be unable to help so many people. That feeling is something all first responders remember from that day.

That’s one reason that every year on September 11, I call Joe Dunne, who told me to put on that Kevlar helmet. I want to always be a reminder to him that there are people he did save, people who are still alive today because of him. Including me.

Who She Was

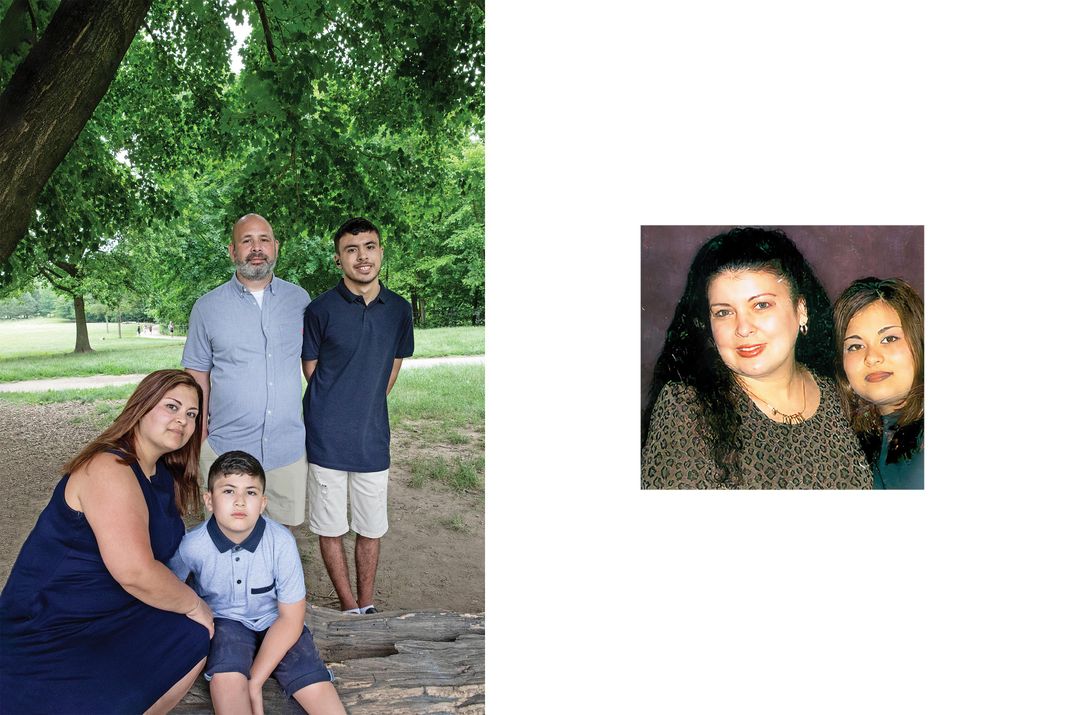

Angilic Casalduc Soto | Daughter of Vivian Casalduc, microfiche clerk for Empire Blue Cross Blue Shield

“Why take a cab when you can walk and see the world?” That was one of my mother’s favorite sayings. She used to take the train through Brooklyn and then walk over the Manhattan Bridge so she could look at the boats on the pier. At lunchtime, or after work, she’d go down to the park and listen to musicians playing salsa. She’d get up and dance—sometimes with co-workers, sometimes with strangers. She could make an ordinary workday feel like a festival.

She was the cool mom in my neighborhood. When my friends were fighting with their parents, they’d come over to my place and my mom would talk them through it. She could always see things from both points of view—the parent’s and the child’s. And if my friend didn’t want to go home, my mom would say, “Okay, I’ll call your mom and let her know you’re here.”

When I was 16, I lost a friend in a devastating tragedy. Let me tell you, this woman, she was there, she understood. She talked to me. She listened. I never wanted to eat, so she blended up vitamins and put them in protein shakes. And she was there like that for my two older brothers and my stepsister.

Without my mom, I don’t know how I would’ve finished high school. She used to tell us, “Do what makes your blood pump. You need to be passionate about what you do because life is short.”

When I got my associate’s degree, she came to my graduation and then took me to lunch at one of her favorite restaurants. I kept telling her it wasn’t a big deal—I was planning to go on and get a bachelor’s. But she said, “You have to mark every accomplishment as a celebration.” And you know what? I’m extremely grateful because she wasn’t around for any other celebrations after that.

The night before 9/11, my mom told me she wasn’t feeling well and I said, “Don’t go to work if you’re sick.” The next morning, she wasn’t there to meet me at our usual subway stop—we used to meet up along our commute and ride into the city together. I thought maybe she’d stayed home, but I called my brother and he told me she’d gone in earlier.

When I got to my job in Midtown, that’s when I heard about the towers. I ran outside, and when I got to the area, the South Tower had just come down. People were running around screaming. It was smoky and foggy. I saw people jumping, people falling—it was complete chaos.

I don’t remember how I got home. One of my brothers was there and my other brother came to meet us. We went through our photo albums and took out all the pictures we could find of our mother. Then we went to all the hospitals, the shelters, the schools, everywhere they were putting out beds. We gave all the pictures away thinking, “We’ll find her and we’ll get more of her pictures down the line.” This would never happen.

My mom worked on the 28th floor of the North Tower. It wasn’t one of the highest floors and people were able to get out. Later on, a co-worker of hers told us they’d seen my mother coming down, but she’d gone back in to help somebody.

For the longest time, I was very angry. My mom wasn’t a firefighter or an EMT. She wasn’t trained to go back into a building during an emergency. I felt like, How dare you go back in, knowing you had children of your own? She only got to meet a few of my nieces and nephews. She doted on them and took them everywhere, baked them cakes and cookies. My children missed out on all that.

But I have to remember what type of lady this was. This was a lady who would see a pigeon with a broken wing and nurse it back to health. This was a lady who would feed all our friends and neighbors. This was a lady who used to take all the children on the block outside to roller-skate and play handball. Of course she went back to help someone. That’s who she was.

At least I didn’t miss out on having my mom bake for me, play with me, take me to school or help me with my homework. I got 23 years with her. I have to be grateful for that. Somehow, that’s what was meant to be.

Connection

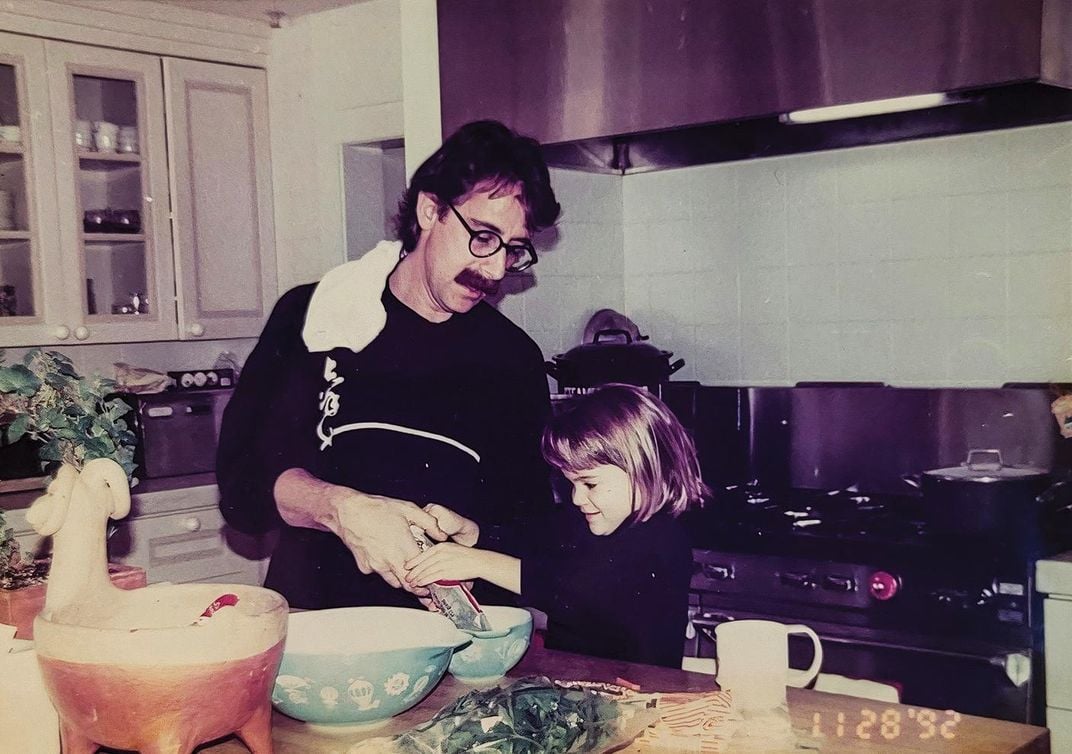

Hali Geller | Daughter of Steven Geller, trader at Cantor Fitzgerald

My dad and I used to cook together. When we went out to our house on Long Island, we’d make marinades and huge numbers of courses, with lots of starters and things to pick on. In the city, we mostly made weeknight things like pasta with spinach and Italian sausage. There was always room for spaghetti and meatballs—we’d make the meatballs, of course.

Shopping at Zabar’s with my dad was really special. He knew everyone’s names and they knew his. It set such a good example of how to treat people. The man behind the fish counter mattered as much to my dad as his bosses at Cantor Fitzgerald.

When the planes hit the World Trade Center, I was 12 years old, in class on the Upper West Side. I was in denial at first. As a kid, you’re going to have dreams of the person you love walking through the door again. I leaned on my friends a lot because they’d known my dad. And even though not everyone in New York City lost someone on 9/11, all of us went through it together. That helped.

The hardest part was when a therapist encouraged my mom to send me to a wilderness program in northern Maine. It was eight weeks long, in the dead of winter, and then I was sent to a boarding school for troubled kids. I had yet to be exposed to people who had major traumas from sexual or mental abuse. Suddenly, I was surrounded by kids who’d been self-harming, using drugs, participating in crimes. Maybe those programs helped some people, but for a kid like me, being thrown into them was almost harder than losing my dad. I put on a brave face for my mom, but looking back, it would have been much better for me if I’d gotten local support while just living my life. Instead, I spent much of my teenage years simply trying to survive.

Everything changed the summer before my junior year of high school when I did a program at the Julian Krinsky Cooking School outside Philadelphia. Cooking made me feel close to my dad. When I started touring colleges, I only looked at programs that were culinary-focused. My dad would have been so jealous. I kept thinking, “Man, I wish he could see this!”

For years, when I’d go to Zabar’s or our corner bodega, there were people who remembered me. They knew what happened to my father and always treated me with the utmost kindness. It was nice to go there and see a familiar face and feel a flash of connection with my dad. Because they knew him too.

Hero

Laurel Homer | Daughter of LeRoy Homer Jr., first officer of Flight 93

I have a memory that I’m not even sure happened. I was really little and I was at an event in some sort of banquet hall. They were showing a slide show and a photo of my dad came on. I recognized his picture and pointed to it. I remember the noises people made. It sounded like they were sighing in pity. I think that’s when I first really knew he was gone.

My dad’s plane went down when I was 10 months old, so everything I know about him comes from other people. His father was from Barbados and his mother was from Germany. I know he was very smart —he did his first solo flight when he was just 16—and people tell me he was a good, caring person.

When my mom first told me what had happened to my dad, she said that there had been bad men on his plane. She explained it the best way she could, but it ended up making me scared of men. I know that isn’t rational because my dad was a man and there were really good men on that plane. I remember talking about it with a child therapist while I was playing with toys. That fear is still something I struggle with today.

When I was going into third grade, a certain teacher asked to have me in her class because her cousin had been on my dad’s flight. That helped. Then I started going to Camp Better Days. All the kids there had lost somebody on 9/11. Those people still feel like family because they’re the only ones who know exactly how I feel. One of my friends never met her dad at all because her mom was pregnant with her when it happened. It’s hard to say who had it worse, those who were old enough to remember or those who didn’t even know what we’d lost.

There are a lot of things I’d like to know about my dad, but it’s a difficult subject to talk about, so I usually don’t ask questions. I know everybody thinks of him as a hero, but obviously, I’d rather have grown up with a father. So when people call him a hero, it doesn’t mean that much to me. He didn’t have to die to be my hero, because I still would’ve looked up to him if he were here.

One of My Friends

Danny Pummill | Former lieutenant colonel, United States Army

It started like any other morning. I’d recently come to Washington after leading a battalion command in Fort Riley, Kansas. I was at a Pentagon meeting with Gen. Timothy Maude and we were three copies short of the briefing. Sgt. Maj. Larry Strickland said, “Sir, I’ll run and get a few more copies.” The general said, “No, we’ve got a brand-new lieutenant colonel! Pop over and make some copies. You’re not in battalion command anymore.” Everybody laughed. It was a bit of a hazing.

I went to my desk to get the papers together—and that’s when the roof came down on my head. The walls collapsed. I had no idea what was happening. They’d been doing construction and I figured one of the tanks had exploded. All I knew was that there was black smoke and fire coming out of the hallway and everyone down there was trapped.

I raced down the hall and found a couple of soldiers and a Marine officer. There was a Booz Allen Hamilton computer guy with us, too. We went office to office, telling people to get out. Then the Marine and I tried to get into the burned-out area. The plane had severed the water lines, so we grabbed fire extinguishers. We could hear people, but we just couldn’t get in.

They all died, everyone who’d been in the conference room with me. General Maude, Sgt. Maj. Strickland, Sgt. Maj. Lacey Ivory, Maj. Ron Milam, Lt. Col. Kip Taylor. Kip’s dad was my mentor, the guy who’d talked me into joining the Army. Lt. Col. Neil Hyland also died at the Pentagon that day. He was one of my very best friends.

Of the 125 people we lost in the building on 9/11, 70 were civilians. There were two ladies who had been there for decades. A colonel grabbed them and broke through walls and rescued them, dropping them into the courtyard. It saved lives having military people there. Most didn’t panic. Everyone knew first aid. Maj. Patty Horoho, who became surgeon general of the Army, rounded up everyone who had medical training. It was impressive.

I was coming around a corner when I ran into a man in a suit. The Marine snapped to attention but I was in a bit of shock. The man said, “Do you know who I am?” I said, “Nope.” He said, “Well, I outrank you and I want you to leave the building.” I refused and we got into a big argument. He finally said, “I’m Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. An airplane hit the building and these fumes are dangerous. You’ll die if you go into that area.” Later on, after the Marine and I were given the Soldier’s Medal, someone took a photo of me with Secretary Rumsfeld. He’s laughing and pointing at me, saying, “You’re the only guy who ever swore at me like that!”

After the attack, I helped set up aid and services. We went to Congress to change the law so the families could get retirement benefits. I’d planned to leave the Army in 2006, but I stayed until 2010. Then I became acting undersecretary for benefits at the Department of Veterans Affairs. When I left in 2016, I started my own private company, Le’Fant, which helps solve problems at the VA and other government agencies. I’m especially committed to hiring veterans and military spouses. I wouldn’t have done any of that if it hadn’t been for 9/11. I had to help the people who were left.

I have seven grandchildren now and none of them were alive when 9/11 happened. To them, it’s ancient history. But for those of us who were there, it’s something we still think about every night when we go to bed. Even Pearl Harbor seems different to me now. It rips your heart out when you realize all those people in Hawaii were just coming out of their houses that morning and saw airplanes overhead dropping bombs. They weren’t at war. They were just husbands and wives and clerks, all doing their jobs, all supporting one other.

The Last Place

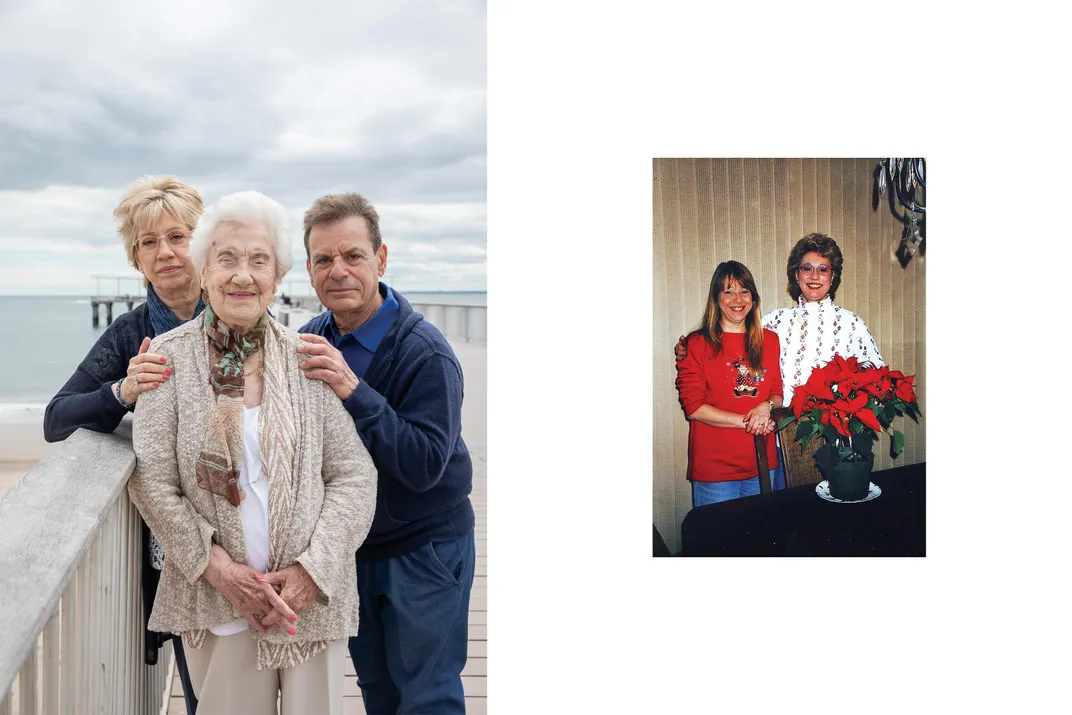

Anita LaFond Korsonsky | Sister of Jeanette LaFond Menichino, assistant VP at Marsh McLennan

Jeanette was four years younger than me, my little sister in every way. Even as an adult, she was just 5-foot-1. She was an artist, went to art school, never finished college, but she got a job at an insurance company and ended up becoming an assistant vice president at Marsh McLennan.

As I often did before starting my workday, I called Jeanette on September 11, but she didn’t pick up. I went to get coffee. Then a co-worker came in and said he’d heard that a plane had just hit the North Tower. I remember thinking, “Wow, somebody really doesn’t know how to fly a plane!” I tried to call my sister again but there was still no answer.

As my co-workers and I watched on our computers, I saw the gaping, fiery hole in the North Tower. The part of the building where my sister worked no longer existed. It didn’t take long before we saw the buildings collapse. And that was it. Just like that, I knew in my heart that I would never see my sister again.

At four o’clock that afternoon, I was sitting in my living room in New Jersey, looking out the window at the clear blue sky. My only thought was, “Where is she?” As a Catholic, I’d always had faith in God, but I don’t know that I expected an answer.

It wasn’t like the burning bush or anything, but I suddenly had a feeling—not even necessarily in words—of God telling me, “Don’t worry. She was so close to heaven, up on the 94th floor, that I just reached down and took her by the hand. She is safe now.” From that moment, I knew that I would miss her terribly, but I was able to move on with my life.

My husband, Michael, was almost at the World Trade Center that day. He was planning to go to a conference that had been scheduled for September 11, but they’d pushed it back to September 13. I don’t really think in terms of God saving my husband but not saving my sister. There are reasons. They might not be reasons we’ll ever be able to understand.

Now that my mom is 97, it would be wonderful to have my sister around to help out. A lot of times, I have the feeling, “I wish you were still here.” It still feels like she’s supposed to be here at this point in my life. But I don’t hold any anger about it. I’m just not that kind of person.

For my mother, it was an insane loss. She ended up volunteering at the 9/11 Tribute Center to lead walking tours of the World Trade Center site. She talked about the events of 9/11 and losing my sister. It was almost like a form of therapy for her. She found solace with fellow tour guides who’d also lost loved ones on that day. She led something like 450 tours.

It took a while before I was able to go to the memorial. But eventually it became a place of contemplation. My sister loved her job. She always said, “Out of all the offices in the city, how did I get lucky enough to be working in this building, with this view?” When I’m standing at the reflecting pool in front of Jeanette’s name, I don’t feel grief. I know it sounds strange, but it’s a place of life for me. Because it’s the last place where my sister was alive.

Conversations

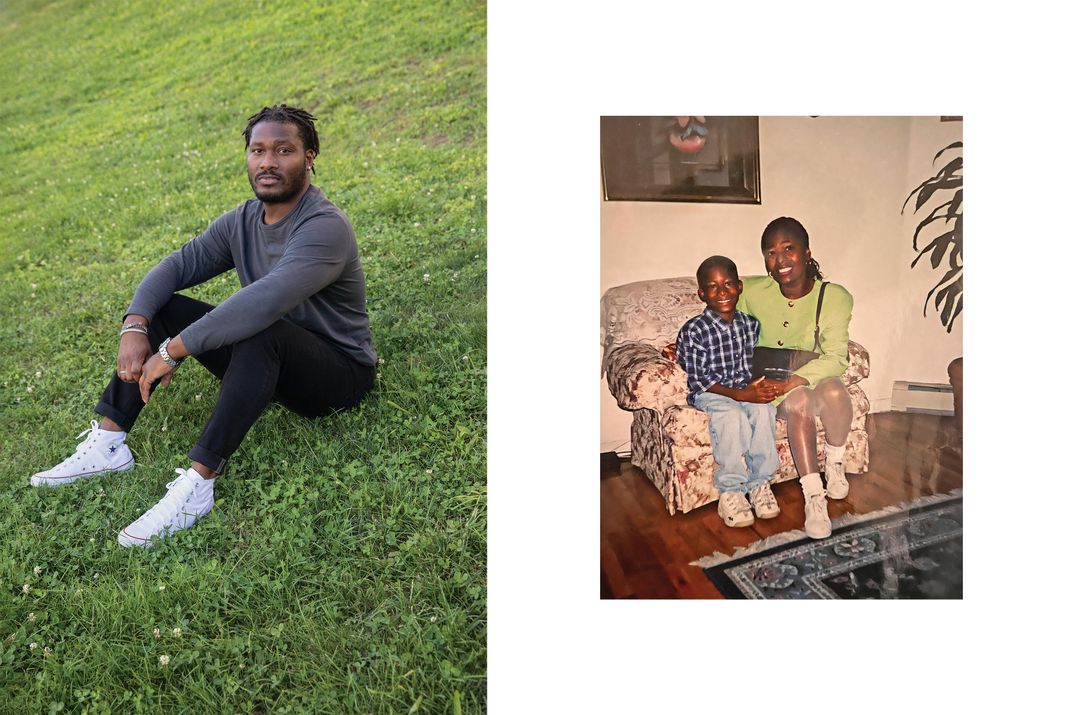

M. Travis Boyd | Son of Elizabeth Holmes, communications department at Euro Brokers

For a long time, I had faith that God was going to bring my mom back to us. My godmother worked with my mom in the South Tower and she’d made it out. After the plane hit the North Tower, my mom came to get her and said, “Hey, we got to get out of here!” As they were walking down the staircase, my mom told her, “I’ll meet you downstairs. I have to go get my purse.” My godmother was down at the 12th or 13th floor when she felt the second plane hit. By the time she got outside, the building was starting to crumble behind her. She ran for her life, but all she could think was, “Where’s Liz?” She thought my mom had probably gotten out. Maybe she’d gone down a different staircase.

About a week later, someone called my aunt’s house and said, “We have Elizabeth Holmes here.” Everyone was so excited: “Thank God, they found Liz!” I thought, Of course they did, and I went to school, knowing I’d see my mom when I got home.

But when I got home that day, she wasn’t there. My aunt and uncle and relatives came up from South Carolina, but someone brought them to another woman named Elizabeth Holmes, in New Jersey. They were devastated. My mom was the person in the family who always brought life and laughter everywhere she went, even to a funeral. She lit up every room. Strangers would see her and ask, “Who is that?”

I was 12 when she died and I made it all the way through high school without fully giving up my faith that my mom was alive. I stayed active in church and on the track team. I kept doing my schoolwork. All the while, I kept telling myself that my mom’s body had never been found. Someone had sent us back an ID card, bent up but still in good shape. Maybe she’d dropped it in the street. Maybe she had amnesia and she was still out there somewhere. I watched every TV show that came out about 9/11 because I thought maybe it would help me find her.

I remember the exact moment I realized she wasn’t coming back. I was 18 and my aunt had just dropped me off at college. I was putting up a picture of my mom and me on the wall of my dorm room and suddenly I broke down and cried. That’s when my grieving process really started. I no longer believed God was going to bring my mother back.

But I knew that God’s spirit would guide me in the right direction, that my life could fulfill my mother’s legacy. That’s what I’ve been trying to do ever since. My mom gave me so much wisdom, even at a young age. I saw how she loved and respected people. I saw how much she cared about education. I became a schoolteacher, and I created the Elizabeth Holmes Scholarship Foundation, where we help support four or five kids who are heading to college. I’m graduating with my doctorate in August, just before the 20th anniversary of my mom’s passing. I’m also an ordained minister. My faith allows me to believe that I’ve made my mom proud.

That doesn’t mean I never question the way she died. Religion is all about building a relationship with God, and you build relationships through conversations. I don’t know whoever said you should never question God. If you never question God, you never get any answers.

Life of the Party

Patty Hargrave | Wife of T.J. Hargrave, VP at Cantor Fitzgerald

Everyone knew who T.J. was in high school. Of course they did! He was the kid who was in the soap opera “Guiding Light.” He had beautiful curly hair. One day, after a bet with a friend, he shaved his head and they fired him from the show. They replaced him with Kevin Bacon—talk about six degrees of Kevin Bacon!

T.J. and I both dropped out of college after a year and that’s when we started dating. After paying his dues, he eventually got a job as a broker and he was great at it. He worked among Harvard and Yale graduates and when people found out he hadn’t even graduated from college, most of them scratched their heads. He was as smart, if not smarter than anyone I knew.

When T turned 30, he asked me to throw a big party. Not a lot of things bothered him in life, but he kept saying, “I’m not going to make it to 40, so I want 30 to be my big celebration.” I still don’t know why he said it. He just felt in his heart that he wasn’t going to live another ten years.

He was 38 when the plane hit the North Tower. He called me from his office on the 105th floor and said, “Something terrible has happened. We’ve got to get out of here. We’re running out of air.” I heard people screaming. I said, “T, do you want me to call 911?” He said, “No, just call me back on my cellphone.”

I couldn’t reach him for the rest of the day. I kept hitting redial. Our daughters were 4, 6 and 8. By the time I went to get them from school, it had been a couple of hours since I’d talked to T. When we pulled up to the house, there were crowds of people there—neighbors coming over with trays of sandwiches, relatives pulling up in their cars. The kids thought we were having a party.

I sat up all night and redialed, never receiving an answer. The next morning, I called my cousin Tommy in Ohio. He was a minister and he’d officiated at our wedding. He kept saying, “No, not yet, Patty,” but I told him, “Tommy, I know he’s gone.” Even then, T’s only brother, Jamie, spent three days traipsing around the city looking for T, to the point where someone had to bring him a new pair of shoes.

I later found out that T.J.’s desk mate had survived. They used to take turns going down to greet visitors. It was his desk mate’s turn that day and the planes hit just as he reached the lobby. It was all a matter of where you happened to be.

That first year, my oldest daughter, Cori, came home crying and said that someone had pointed at her and told a new kid, “That’s the girl who lost her father on 9/11.” I told Cori, “Look, this doesn’t define who you are. You’re an excellent student. You love soccer and you play the piano. You’re kind. And you lost your father on 9/11.” And yet each year, my kids had to sit there knowing that everyone’s eyes were on them as their classes took that artificial moment of silence. Then the teacher would say, “Open your math books to Page 49.”

After T.J. died, the girls and I spent a lot of time with family members and friends. A lot of time. Their comfort and care were instrumental in getting us through years of trying to figure out how to move forward in life. And because of them we came out on the other side, still scathed, but back to some sense of normalcy.

I often wonder what our lives would have been like had we not lost T. How different would the girls be? Would they have chosen different hobbies, schools, careers? T was the fun one, the outgoing one, the life of the party. He was a tremendous father for his short time as one, and I believe he would’ve continued growing better and better as he gained more experience. I missed having him here to celebrate our girls successes, and to comfort them in sad times. I often wonder if we would’ve survived the trials and tribulations that tear so many marriages apart. I don’t have a crystal ball, but I think we would’ve come through.

We had a really good relationship. I remember our last night together so vividly. The girls were asleep and we were sitting on our kitchen counters, drinking wine, talking about what a great life we had. We went to bed that night and he left for work in the morning. The last time I heard from him was that phone call.

I don’t believe in the old saying, “Never go to bed angry.” Sometimes you have to go to bed angry! But on the night of September 10, 2001, we didn’t. I’ll always be grateful for that.

The Last Weekend

Tara Allison | Daughter of Robert Speisman, executive VP at Lazare Kaplan International

I’d just started my freshman year at Georgetown and I was so homesick. I was really missing my family. I called my parents crying and my dad said he’d rearrange his upcoming business trip to stop and see me in Washington, D.C. He came down on Sunday, September 9. We went to dinner and he took me to a movie. It was just the little taste of home I needed.

I was in sociology class on the morning of September 11 when information started coming in. My dad had just left for his flight that morning, and at first, I didn’t think I had any reason to worry. Everything we were hearing was about New York. My grandfather was flying out of LaGuardia that day, and that’s what I was concerned about. But my grandfather’s flight was grounded and then he got off the plane. It didn’t even cross my mind to worry about my dad.

There was a shelter-in-place order in D.C., but since we were college kids, we ignored it and went up to the rooftop. We didn’t actually see the explosion happen, but we could see smoke coming from the Pentagon. Then we went down and turned on the news and I saw a crawl that said, “American Airlines Flight 77 is missing.” That’s when I knew. And of course this isn’t rational, but my first thought was, “I made him come!”

Georgetown was where my dad had last seen me, and he’d been so happy I was there. So I finished my degree and did really well, and then I went on to graduate school at Georgetown to study counterterrorism. A friend in my program introduced me to a military man who later became my husband. I’d just accepted an internship for my dream job in D.C. when he got stationed in Kansas. I picked up everything and moved to Kansas with him. But even that was in the context of my dad, because I felt so drawn to my husband for what he was doing and fighting for.

My husband went on to serve three tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. Now he’s working at West Point. It’s strange, because my parents were hippies, flower children, Vietnam protesters. They had no connection to the military whatsoever. But life was different before 9/11. My mom’s mindset changed and so did mine. I have a unique place in that I am connected to 9/11 both on the military side and the civilian side. To this day, people in the military have an amazing amount of reverence and respect for 9/11 victims. For a lot of them, 9/11 is the reason they joined the armed forces.

I’ve always been a type A person, and I’ve really struggled with the fact that something so terrible happened and it was completely outside of my control. Because of that, and because of the guilt, I’ve kept myself active, moving forward, finding things to do. I’ve been afraid to stop and be stagnant and dwell on it. I think it's both a blessing and a curse to be that way. I keep moving forward, but I think there’s a lot I still haven’t processed, 20 years later.

And yet those last two days with my dad were an incredibly special time. Before that, when I was still living at home, we had a pretty typical father-daughter relationship. But that trip was the first time we were able to spend time together as adults, as buddies. And he was so proud of me. That’s something I’ll remember for the rest of my life.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f0/f6/f0f6371e-396a-4455-ba3b-cc6c83584731/mobile-opener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/48/99489a1b-7bc1-4e40-a694-8c6f008684f9/socialmediaopener.jpg)