Outlaw Hunters

The Pinkerton Detective Agency chased down some of America’s most notorious criminals

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/pinkerton631.jpg)

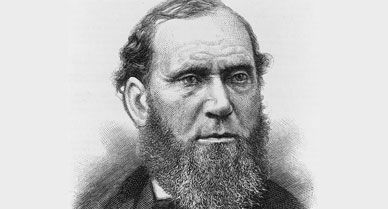

Allan Pinkerton was furious when he got the news. Joseph Whicher, a trusted agent of Pinkerton's National Detective agency, had been discovered in the Missouri woods, bound, tortured and shot dead—yet another victim of Jesse James, the outlaw whose gang Whicher had been assigned to track down. Not only outraged but humiliated by the failure, Pinkerton vowed to get James, declaring, "When we meet it must be the death of one or both of us."

Pinkerton dedicated his life to fighting criminals like Jesse James, and at one point was called the "greatest detective of the age" by the Chicago Tribune. For almost four decades, he and his agents captured bank robbers and foiled embezzlers. But Pinkerton had not set out to become America's original private eye; the humbly-born Scottish immigrant stumbled into crime-fighting.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1819, Allan Pinkerton had grown up poor, helping to support his family as a laborer after his father, a policeman, died in the line of duty. As a young man Pinkerton spoke out for democratic reform in Great Britain and was persecuted for his radicalism. In 1842, politics forced Pinkerton and his wife, Joan, to immigrate to America. The couple wound up in the small town of Dundee, 40 miles outside Chicago, where Pinkerton set up a cooperage, or barrel business.

One day in 1847, Pinkerton ran out of barrel staves and went to look for more wood on an uninhabited island in a nearby river. There he discovered the remains of a campsite. It struck him as suspicious, so he returned at night to find a group of counterfeiters manufacturing coins. Not one to tolerate criminal behavior, Pinkerton fetched the sheriff, and the gang was arrested. At a time when rampant counterfeiting endangered businesses, local merchants lauded Pinkerton as a hero and began asking him to investigate other incidents.

"I suddenly found myself called upon, from every quarter, to undertake matters requiring the detective skill," Pinkerton wrote in an 1880 memoir. He became so good at running sting operations to catch counterfeiters that the sheriff of Kane County, Illinois, made him a deputy. In 1849, Pinkerton was appointed Chicago's first full-time detective, and he gave up the barrel business for good. He founded Pinkerton's Detective Agency in 1850, setting up his first office in downtown Chicago. By 1866, the agency had branches in New York and Philadelphia.

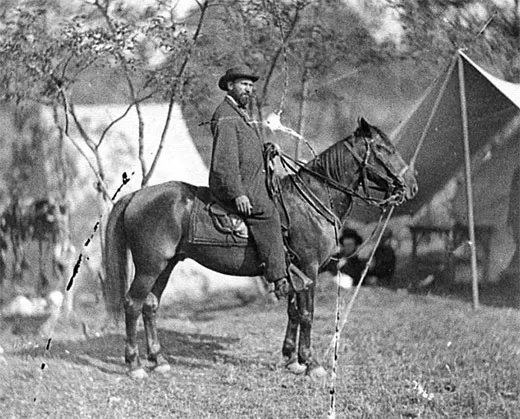

In the mid-19th century, police forces were small, often corrupt and unwilling to follow suspected criminals outside their own jurisdictions. People did not feel that the police were watching out for them, and Pinkerton took advantage of this deficiency, creating Pinkerton's Protective Police Patrol, a corps of uniformed night watchmen who protected businesses. Soon these "Pinkerton men," as they were called—though a few undercover agents were women—were as important to law enforcement as official police. As the railroads sped west, a new task arose: hunting down outlaws.

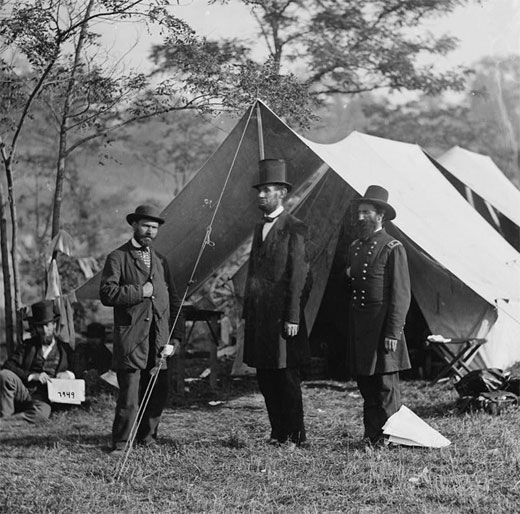

The outlaws of the 19th century have been much-romanticized in popular culture, but they were actually dangerous, ruthless and often brutal. Criminals like Jesse James and his brother Frank murdered anyone who got in their way; the 1874 killing of Joseph Whicher was characteristic behavior. An active bank and train robber since 1866, James was also an unreformed Southern secessionist. Pinkerton, who had worked for the Underground Railroad and once guarded Abraham Lincoln's train, was especially eager to bring Jesse James to justice.

The Pinkerton agency usually succeeded when it came to capturing criminals. Toward the end of his life, Pinkerton authored a popular book series based on his agency's most famous cases—prototypical true-crime stories that inspired later detective writers. In Bank-Robbers and the Detectives, Pinkerton explained his accomplishments by citing "well-directed and untiring energy" and "a determination not to yield until success was assured."

In the late 1860s, the Pinkerton agency captured the Reno brothers' gang, the first organized train robbers in the United States—Pinkerton himself chased Frank Reno all the way to Windsor, Ontario. During that same period, Pinkerton detectives nabbed several more high-profile bank and train robbers, in some cases recovering thousands of stolen dollars. In one instance, Pinkerton men followed another group of bandits from New York to Canada, where they arrested them and recovered nearly $300,000 in cash. The agency gained a reputation for tenacity, and citizens, terrorized by outlaws, looked to the Pinkertons as heroes.

After Whicher's murder, Pinkerton sent more agents after the James gang. In January 1875, a group of Pinkerton men and a local posse, responding to a tip, rushed to James' mother's Missouri farm. The mother, Zerelda Samuel, was mean, ugly and strong-willed, as well as a dedicated slaveholder and secessionist. Still angry about the way the war had turned out, Samuel saw Jesse and Frank, the sons by her first marriage, as freedom fighters for the downtrodden southern states, rather than mere bandits and murderers. When the Pinkerton-led raiders appeared on her farm late one night, she refused to surrender.

A standoff ensued, and someone threw a lantern into the darkened house, purportedly to aid visibility. There was an explosion, and the posse ran in to find Zerelda Samuel's right arm blown off. Reuben Samuel, her third husband, and their three young children had also been inside. To the detectives' horror, 8-year-old Archie, Jesse James' half brother, lay fatally wounded on the floor.

The death of Archie Samuel was a public relations nightmare for Pinkerton's Detective Agency. Not only had the Pinkerton agency again failed to capture Jesse and Frank James (the brothers had been tipped off and weren't at the house that night), but a little boy had been blown up and Zerelda Samuel was calling for blood. Public opinion, which until then had mostly supported the Pinkertons, shifted. One sensational biography of James, published a few years after his death, ruled that the explosion was "a dastardly piece of business … a cowardly act, thoroughly inexcusable." Though Pinkerton insisted it was one of locals, not one of his men, who threw the bomb, the tragedy did much to build Jesse James' legend and stain the Pinkerton agency's reputation.

For the first time, the man who once said he did "not know the meaning of the word 'fail' " had been defeated. It would be seven more years before James met his end, at the hands of a fellow criminal seeking a $10,000 bounty.

Despite the lowered public approval, Pinkerton's Detective Agency continued to operate after the Archie Samuel incident. Pinkerton men captured more criminals; broke up the Molly McGuire gang of Irish terrorists; and pursued Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid to Bolivia, where the bandits were killed by local law enforcement. Toward the end of the 19th century, the agency became more involved in labor disputes, always on the side of management. This sort of operation did little to help the agency's reputation, especially when Pinkerton men inadvertently incited a deadly 1892 riot at a steel mill in Homestead, Pennsylvania. The name "Pinkerton" soon became a dirty word among the working class.

Pinkerton died on July 1, 1884, and his obituary in the Chicago Tribune described him as "a bitter foe to the rogues." By that time, his son William had taken over the agency's Chicago headquarters, and his son Robert had taken over operations in New York. In the 20th century, the agency gradually shifted its focus from detective work to private security, and it remained a family-run company until Robert Pinkerton II, Allan's great grandson, died in 1967. He left a corporation with 18,000 employees and 63 branches across the United States and Canada.

Today, as a subsidiary of an international company called Securitas Group, the Pinkerton agency provides private security for businesses and governments around the world. Pinkerton Consulting and Investigative Services protects shipping containers from terrorists, conducts background checks and guards executives for many Fortune 500 companies, says Pinkerton General Counsel John Moriarty. "We're proud to be able to claim direct descent back to 1850," he says. "There are no other companies providing this kind of service that can trace their origins back to the beginning." In a way, he says, "even the FBI and the Secret Service are descendants of the Pinkerton Agency."

Though Pinkertons no longer hunt down outlaws, the agency kept a vast archive of historic criminal files and mug shots until 2000, when it donated the materials to the Library of Congress. The collection included a full drawer on Jesse James.

Former Smithsonian editorial assistant Amy Crawford attends the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)