On Heroic Self-Sacrifice: a London Park Devoted to Those Most Worth Remembering

In 1887, a painter was inspired by an idea: commemorate the everyday heroism of men, women and children who had lost their lives trying to save another’s

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/800px-Postman%27s_Park_web.jpg)

No nation is short of monuments to its heroes. From the Lincoln Memorial and Nelson’s Column to the infamous gold-plated statue of Turkmenbashi—which until its recent demolition sat atop a 250-foot-high rotisserie in Turkmenistan and rotated throughout the day to face the sun—statesmen and military leaders can generally depend upon their grateful nations to immortalize them in stone.

Rarer by far are commemorations of everyday heroes, ordinary men and women who one day do something extraordinary, risk all and sometimes lose their lives to save the lives of others. A handful of neglected monuments of this sort exist; of these, few are more modest but more moving than a mostly forgotten little row of ceramic tiles erected in a tiny shard of British greenery known as Postman’s Park.

Postman's Park, a small slice of greenery in the middle of the City of London—heart of the British capital's financial district—is home to one of the most unusual and moving of the world's monuments to heroism. Photo: Geograph.

The park—so named because it once stood in the shadow of London’s long-gone General Post Office building—displays a total of 54 such plaques. They recall acts of individual bravery that date from the early 1860s and are grouped under a plain wooden awning in what is rather grandly known as the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice. Each commemorates the demise of a would-be rescuer who died in the act of saving someone else’s life.

The modesty of the plaques, and of the lives they mark, lends Postman’s Park a stately sort of melancholy, but visitors to the monument (who were rare until it was dragged out of obscurity to serve as a backdrop and a crucial plot driver in the movie Closer a few years ago) have long been drawn to the abiding strangeness of the Victorian deaths they chronicle. Many of those commemorated in the park died in ways that are rare now—scalded on exploding steam trains, trampled under the hooves of runaway horses, or, in the case of the ballet dancer Sarah Smith, onstage, in a theater lit by fire light, “of terrible injuries received when attempting in her inflammable dress to extinguish the flames which had enveloped her companion.”

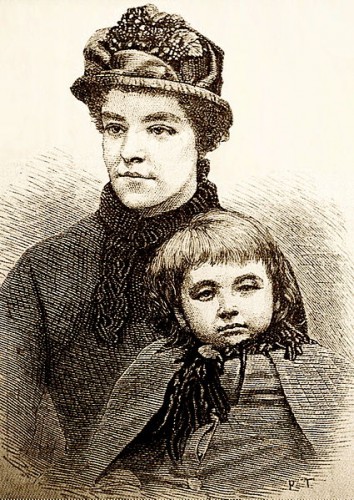

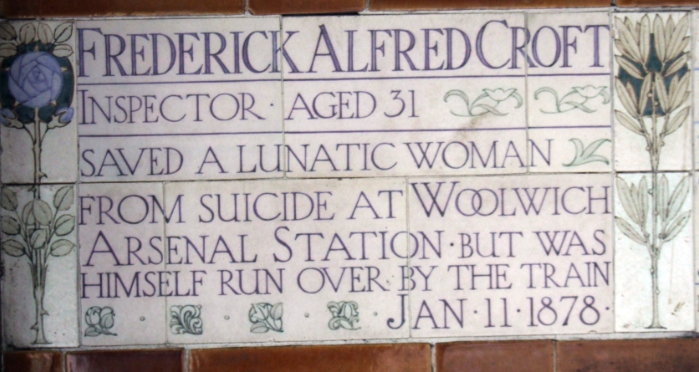

The Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice was the brainchild of George Frederic Watts, a painter who, while eminent in the Victorian age, harbored a hatred of pomp and circumstance. Twice refusing Queen Victoria’s offer of a baronetcy, Watts always identified strongly with the straitened circumstances of his youth; he was the son of an impoverished piano-maker whose mother died while he was young. For years, in adulthood, Watts habitually clipped newspaper stories of great heroism, mostly by members of the working classes. At the time of Victoria’s jubilee, in 1887, he proposed the construction of a monument to the men, women and children whose deeds had so moved him—people like Fred Croft, a railway inspector who in 1878 attempted to “save a lunatic woman from suicide at Woolwich Arsenal Station but was himself run over by the train,” or David Selves, who drowned, aged 12, in the Thames with the boy whom he had tried to save still clinging to him.

Selves, his plaque notes—in language typical of the day—“supported his drowning playfellow and sank with him clasped in his arms.” He was the youngest of 11 children, and an elder brother, Arthur, had also died of drowning eight years earlier. His death is memorialized a few feet away from that of Solomon Galaman, who dragged his younger brother from under the wheels of an approaching carriage, only to be crushed himself. As his distraught parents rushed up to the scene of the accident, he died with the words: “Mother, I saved him, but I could not save myself.”

Watts memorial to David Selves, one of many Victorian children commemorated at Postman's Park who died by drowning. Photo: Ronnie Hackston.

Watts got nowhere during the jubilee—public attention was elsewhere, and his idea lacked popular appeal at a time when imperial heroes who had conquered new territories for Queen and country stood higher in the public’s favor. Ten years later, though, he was able to scrape together the £3,000 needed to fund a memorial considerably more modest than the one he had originally conceived. Even then, he was forced to bear the £700 (about $90,000 today) cost of the wooden gallery that housed the plaques himself.

The woman whose bravery first inspired Watts’ idea for a memorial, Alice Ayres, is a good example of the sort of hero that the painter considered worth commemorating. Ayres was a nursemaid who in April 1885 saved the lives of two of her three charges—then age 6, 2 and 9 months–when their house caught fire. Spurning the chance to save herself, she dragged a large feather mattress to an upstairs window, threw it to the ground, and then dropped the children to it one by one, going back twice into the flames and smoke to fetch another while a crowd outside cried out, begging her to save herself. One child died, but the other two survived; Ayres herself, overcome by smoke, fell from an upper window to the sidewalk and died several days later of spinal injuries.

It was typical of Watts, and of the era he lived in, that it was thought worth mentioning on Ayres’s plaque that she was the “daughter of a bricklayer’s labourer.” Heroism, in those days, was regarded as a product of character and hence, at least to a degree, of breeding; it was something one would expect of a gentleman but be surprised to find in his servant. Watts was determined to drive home the point that it could be found everywhere. Not mentioned was the equally notable fact that the lives Ayres saved were those of her sister’s children; she had been working as a servant to her better-off nephews and nieces.

Alice Ayres, a nursemaid who saved the lives of two children caught with her in a burning house, at the expense of her own. Illustration: Wikicommons.

Unlike most of the men, women and children commemorated at Postman’s Park, Ayres became a celebrated heroine, the subject of chapters in educational and devotional books. Less well recalled in those days were the many whose self-sacrifice did not involve the rescue of their betters (or, in the case of John Cranmer of Cambridge—dead at age 23 and commemorated on another plaque that says so much about the age—the life “of a stranger and a foreigner.”) The names of Walter Peart and Harry Dean, the driver and the fireman of the Windsor Express—who were scalded to death preventing a hideous rail crash in 1898—linger somewhere deep in the nation’s consciousness because one of the lives they saved was that of George, Viscount Goschen, the then First Lord of the Admiralty, but the chances are that without Watts no one would recall William Donald, a Bayswater railway clerk who drowned in the summer of 1876 “trying to save a lad from a dangerous entanglement of weed.” Or Police Constable Robert Wright of Croydon, who in 1903 “entered a burning house to save a woman knowing that there was petroleum stored in the cellar” and died a fiery death in the ensuing explosion alarmingly similar to that of Elizabeth Coghlam, who a year earlier and on the other side of London had sacrificed herself to save “her family and house by carrying blazing paraffin to the yard.”

Thanks to the exemplary diligence of a London blogger known as Carolineld, who has researched each of the miniature tragedies immortalized in ceramic there, the stories of the heroes of Postman’s Park can now be told in rather more detail than was possible on Watts’ hand-painted six-inch tiles. Thus we read that Coghlam had “knocked over a paraffin lamp, which set her clothes alight. Afraid that they would set the house on fire and menace her two children who were asleep upstairs, she hurried outside with clothes and lamp blazing.” There is also the story of Harry Sisley, commemorated on one of the earliest and most elaborate tiles for an attempt to save his brother from drowning. That brief summary is supplemented by a local newspaper report, which says:

A very distressing fatality occurred at Kilburn, by which two little boys, brothers, lost their lives. Some excavations have recently been made in St Mary’s-field in connection with building operations, and in one of the hollows thus formed a good-sized pool of water, several feet deep, had accumulated. The two boys—Frank Sisley, aged 11 years, and Harry Sisley, aged nine—sons of a cabdriver, living at 7, Linstead-street, Palmerston-road—were, it appears, returning home from school, when they placed a plank on the pool mentioned, and amused themselves as if in a boat. The raft capsized and the two boys were drowned.

A coroner’s inquest heard the rest of the story:

Having got on a raft, Frank Sisley, in attempting to reach something, fell into the water. His brother jumped in and tried to save him, but they both disappeared. One of the other boys, named Pye, then entered the water with his clothes on, and succeeded in getting Harry to the bank. He was returning to rescue Frank, when Harry uttered an exclamation of distress, and either jumped or fell into the water again. His brother “cuddled” to him, and they went under the water together. Pye then raised an alarm, but when after some delay the bodies were recovered, all efforts to restore animation were fruitless.

G.F. Watts in his studio toward the end of his life.

Watts was so determined to see his project to fruition that he considered selling his house so he could fund the tiles himself. Even so, he had to wait until late in life to see his vision of a memorial to such sacrifices realized. He was 83 years old, and ill, when the Memorial was finally opened, in 1900. He died in 1904, and when his wife admitted she was in no position to fund any more plaques, work on the monument languished. In 1930, the police raised funds to commemorate three officers killed in the line of duty in the intervening years, but other than that lines of tiles in Postman’s Park were not added to again until 2009—when, thanks in part to the higher profile generated by Closer, which was released in 2004, one more plaque was installed to commemorate the heroism of Leigh Pitt, a print worker who had drowned in 2007, at age 30. Pitts’ death would surely have attracted Watts’ attention:He was saving the life of a boy who had fallen into a London canal.

Pitts’ memorial was approved by the Diocese of London, which has charge of Postman’s Park and has indicated it will consider applications for plaques to commemorate other acts, so long as they tell of “remarkable heroism.” It is possible, then, that in good time the 70 remaining spaces left unfilled by Watts may be filled.

Sources

Mark Bills et al. An Artist’s Village: G.F. and Mary Watts in Compton. London: Philip Wilson, 2011; John Price, “‘Heroism in everyday life’: the Watts Memorial for Heroic Self Sacrifice.” In History Workshop Journal, 63:1 (2007); John Price. Postman’s Park: G.F. Watts’s Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice. Compton, Surrey: Watts Gallery, 2008.

Thanks to Ronnie Hackston for permission to use his photographs of Postman’s Park.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)