A Modern Odyssey: Two Iraqi Refugees Tell Their Harrowing Story

Fleeing violence in Iraq, two close friends embarked on an epic journey across Europe—and ended up worlds apart

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/2f/b62f369a-35cf-48bc-8d2e-8a2706c31c5e/apr2017_f01mh_tworefugees.jpg)

It was just after 11 o’clock on a stifling august night when Salar Al Rishawi got the feeling that it might be his last. He and his best friend, Saif Al Khaleeli, had been in the back seat of a banged-up sedan barreling up a highway in Serbia. Iraqi refugees, they were on their way to the Hungarian border, and from there on to Austria. Salar had paid the driver and another smuggler, who was also in the car, $1,500 from the wad of bills that he kept wrapped in plastic and hidden in his underwear; the rest of the $3,300 fee would come later. Suddenly, the driver turned off the highway and parked in a deserted rest stop.

“Policija,” he said, and then unleashed a stream of Serbo-Croatian that neither Iraqi could understand. Salar dialed Marco—the English-speaking middleman who had brokered the deal in Belgrade—and put him on the speakerphone.

“He thinks there is a police checkpoint on the highway,” Marco translated. “He wants you to get out of the car with your bags, while he drives ahead and sees if it is safe to continue.” The other smuggler, Marco said, would wait beside them.

Salar and Saif climbed out. The trunk opened. They pulled out their backpacks and placed them on the ground. Then the driver gunned his engine and peeled out, leaving Salar and Saif standing, stunned, in the dust.

“Stop, stop, stop!” Saif yelled, chasing after the car as it tore down the highway.

Saif kicked the ground in defeat and trudged back to the rest stop—a handful of picnic tables and trash cans in a clearing by the forest, bathed in the glow of a nearly full moon.

“Why the hell didn’t you run after him?” Saif barked at Salar.

“Are you crazy?” Salar shot back. “How could I catch him?”

For several minutes they stood in the darkness, glaring at each other and considering their next move. Saif proposed heading toward Hungary and finding the border fence. “Let’s finish this,” he said. Salar, the more reflective of the two, argued they would be crazy to attempt it without a guide. The only possibility, he said, was to walk back to Subotica, a town ten miles south, slip discreetly onto a bus and return to Belgrade to restart the process. But Serbian police were notorious for robbing refugees, and the duo were easy prey for ordinary criminals as well—they would have to keep a low profile.

Salar and Saif cut through the forest that paralleled the highway, tripping over roots in the darkness. Then the forest thinned out and they stumbled through cornfields, keeping their bearings by consulting their smartphones—crouching low and cradling the devices to block the glow. Twice they heard barking dogs, then hit the soft earth and lay hidden between rows of corn. They were hungry, thirsty and weary from lack of sleep. “We didn’t have papers, and if somebody had killed us, nobody would ever know what had happened to us,” Salar recalled to me. “We would just have disappeared.”

**********

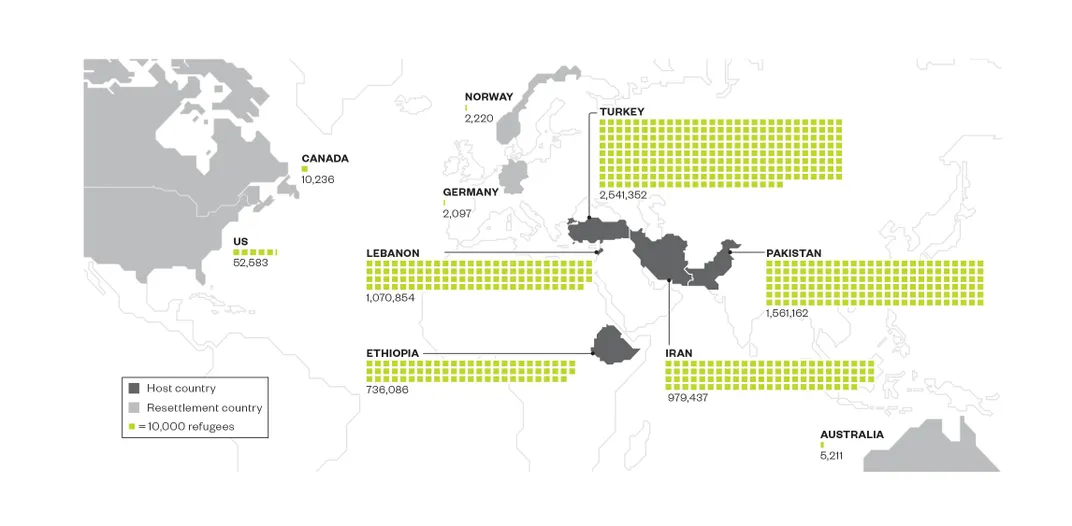

Salar and Saif—then in their late 20s, friends since their college days studying engineering in Baghdad, partners in a popular restaurant, each born into a blended Shia-Sunni family—were among the more than one million people who fled their homes and crossed either the Mediterranean or Aegean Sea into Europe in 2015 because of war, persecution or instability. That number was nearly double the number in any previous year. The exodus included nearly 700,000 Syrians, as well as hundreds of thousands more from other embattled lands such as Iraq, Eri-

trea, Mali, Afghanistan and Somalia. In 2016, the number of refugees traveling across the Aegean dropped dramatically, following the closure of the so-called Balkan Route, though hundreds of thousands continued to take the far longer, more perilous trip from North Africa across the Mediterranean to Italy. The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that some 282,000 made the sea crossing to Europe during the first eight months of last year.

This modern-day Odyssey, a journey through a gantlet of perils that can rival those faced by the hero in Homer’s 2,700-year-old epic, has both aroused the world’s sympathy and created a political backlash. German Chancellor Angela Merkel earned global admiration in 2015 when she expanded her country’s admission of refugees, taking in 890,000, about half of whom were Syrian. (The United States, by contrast, accepted fewer than 60,000 that year, only 1,693 of whom were Syrian.) The number admitted into Germany dropped to about one-third of that total in 2016.

At the same time, populist leaders in Europe, including France’s Marine Le Pen and Germany’s Frauke Petry, head of a surging nativist party called Alternative for Germany, have attracted large and vocal followings by exploiting fears of radical Islam and the “theft” of jobs by refugees. And in the United States, President Donald Trump, just seven days after taking office in January, issued an initial executive order halting all refugee admissions—he singled out Syrians as “detrimental to the interests of the United States”—temporarily barring citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries. The order provoked a national uproar and set off a confrontation between the executive and judicial branches of the U.S. government.

While hostility toward outsiders appears to be on the rise in many nations, the historic masses of refugees themselves face the often overwhelming challenges of settling into new societies, from the daunting bureaucratic process of gaining asylum to finding work and a place to live. And then there’s the crushing weight of sorrow, guilt and fear about family members left behind.

As a result, a growing number of refugees have become returnees. In 2015, according to German Interior Minister Thomas de Maizière, 35,000 refugees returned voluntarily, and 55,000 repatriated themselves in 2016 (25,000 were forcibly deported). Out of some 76,674 Iraqis who arrived in Germany in 2015, some 5,777 had gone home by the end of November 2016. Eritreans, Afghanis and even some Syrians have also elected to head back into the maelstrom. And the pace is quickening. In February, partly as a means of reducing a glut of asylum applications, the German government began offering migrants up to €1,200 ($1,300) to voluntarily return home.

That agonizing quandary—stay in a new land despite the alienation, or go back home despite the danger—is one that Salar and Saif faced together at the end of their long journey to Western Europe. The two Iraqi refugees always had so much in common they seemed inseparable, but the great upheaval that is reshaping the Middle East, Europe and even the United States would cause these two close friends to make different choices and end up worlds apart.

For a friend with an

understanding heartis worth no less than a brotherBook 8

**********

Salar Al Rishawi and Saif Al Khaleeli—their last names altered at their request—grew up five miles apart on the western side of Baghdad, both in middle-class, mixed neighborhoods where Shias and Sunnis, the two main denominations of Islam, lived together in relative harmony and frequently intermarried. Saif’s father practiced law and, like nearly all professionals in Iraq, became a member of the Ba’ath Party, the secular, pan-Arabist movement that dominated Iraq during Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship (and was later excluded from public life). Salar’s father studied aeronautical engineering in Poland in the 1970s, and returned home to provide technical support to agricultural ministry teams fertilizing fields from helicopters. “He carried out inspections, and flew with the pilots in case something went wrong in the air,” remembers Salar, who joined him on half a dozen trips, swooping at 150 miles an hour over Baghdad and Anbar Province, thrilling to the sensation of flight. But after the first Gulf War in 1991, United Nations-imposed sanctions wrecked Iraq’s economy, and Salar’s father’s income was slashed; in 1995 he quit and opened a streetside stall that sold grilled lamb sandwiches. It was a comedown, but he earned more than he had as an aeronautical engineer.

In grade school, the stultifying rituals and conformity of Saddam’s dictatorship defined the boys’ lives. The Ba’athist regime organized regular demonstrations against Israel and America, and teachers forced students en masse to board buses and trucks and attend the protests. “They put us on the trucks like animals, and we couldn’t escape,” Salar said. “All the people [at the rallies] were cheering for Saddam, cheering for Palestine, and they didn’t tell you why.”

In 2003, the U.S. invaded Iraq. Watching American troops in Baghdad’s streets, Salar thought of the Hollywood action movies his father had taken him to as a child. “At first I thought, ‘It is good to get rid of Saddam,’” he recalls. “It was like we were all asleep under him. And then somebody came and said, ‘Wake up, go out.’”

But in the power vacuum that followed Saddam’s fall, freedom gave way to violence. A Sunni insurgency attacked U.S. troops and killed thousands of Shias with car bombs. Shia militias rose up, seeking revenge. “Many Ba’athists were killed by Shia insurgents, so [my father] was too terrified to go out of the house,” Saif says. Salar recalls walking to school one morning and seeing “a pile of dead people. Someone had shot them all.”

After Salar finished high school in 2006, an uncle helped him obtain an administrative job with Kellogg, Brown and Root, the U.S. military contractor, in the Green Zone—the four-square-mile fortified area that contained the U.S. Embassy and the Iraqi Parliament and presidential palace. Salar was a prized hire because of his English proficiency; his father had studied the language in Poland, two aunts were English teachers, and Salar had excelled in high-school English class, where he read American short stories and Shakespeare. But three months into the job—coordinating the Iraqi staff on building projects—militiamen from the Mahdi Army, the anti-U.S. Shia militia, led by Moktada al-Sadr, sent him a frightening message. Determined to chase out the American occupiers and restore Iraqi sovereignty, they warned Salar to quit the job—or else. Dejected, he sent in his notice immediately.

Saif went to work for an Iraqi building contractor, supervising construction projects. Early one morning, at the height of the sectarian violence, he and six workmen showed up to paint a house in the town of Abu Ghraib, a Sunni stronghold next to the infamous prison where U.S. soldiers had tortured suspected insurgents. The homeowner, an imam at a local mosque, invited them in and served them a meal. When one painter blurted out a Shia invocation—“Ya Hussain”—before sitting down to eat, the imam froze. “Did you bring a Shia to my house?’ he demanded of Saif. Saif recognized the danger. “[Radical Sunnis] believe that the Shia are infidels and apostates, deserving death. The preacher said, ‘Nobody will leave this house today,’” he recalls. The imam summoned several armed fighters. “I was begging him, ‘Hajj, this is not true, he is not a Shia,’” Saif says. Then the men turned on Saif, demanding the name of his father’s Sunni tribe. “I was scared and confused and I forgot what my tribal name was. I even forgot my father’s name,” he recalls. After beating Saif and the others and holding them for hours, the insurgents allowed six to leave—but detained the Shia. Saif says that they killed him a short time later.

Salar and Saif survived three bloody years of the U.S. occupation and the insurgency, and began to concentrate on building their careers. Fondly remembering his experience flying with his father, Salar applied to a training school for Iraqi pilots, run by the U.S. Air Force in Italy. He studied for the written exam for months, passed it—but failed the physical because of a deviated septum. He pressed on, studying computer science at Dijlah University College in Baghdad.

One day a rival for a young woman’s affections confronted Salar in the hallway with a group of friends, and began to taunt him. Saif noticed the commotion. “The guy was telling Salar, ‘I’ll put you in the trunk of the car,’” he recalls. “There were five boys against Salar, who was alone. He looked like a peaceful, humble guy.” Saif intervened, calming the other students. “That’s how the friendship started,” Saif says.

Salar and Saif discovered an easy affinity and soon became inseparable. “We talked about everything—computers, sports, friends, our future,” Salar says. “We ate together, barbecued together and drank tea together.” They took extra computer hardware courses together at a Mansour night school, played pickup soccer in public parks, shot billiards at a local pool hall, watched American TV series and movies like Beauty and the Beast together on their laptops, and came to know each other’s families. “We really became like brothers,” Saif says. And they talked about girls. Good-looking and outgoing, both were popular with the opposite sex, though Iraq’s conservative mores required them to be discreet. As the violence ebbed, they would sometimes spend weekend evenings sitting in cafés, smoking shishas (water pipes), listening to Arabic pop music and enjoying the sense that the horrors that had befallen their country were easing. Salar and Saif graduated from college in 2010, but they quickly discovered that their engineering degrees had little value in Iraq’s war-stunted economy. Saif drove taxis in Baghdad and then worked as a tailor in Damascus, Syria. Salar barbecued lamb at his father’s stand for a while. “I was living with my parents, and thinking, ‘all my study, all my life in college, for nothing. I will forget everything I learned in four years,’” Salar says.

Then, at last, things began to break in their favor. A French company that had a contract to clear imports for Iraq’s Customs Department hired Salar as a field manager. He spent two or three weeks at a time living in a trailer on Iraq’s borders with Syria, Jordan and Iran, inspecting trucks that carried Coca-Cola, Nescafé and other goods into the country.

Saif landed an administrative job with the Baghdad Governorate, overseeing construction of public schools, hospitals and other projects. Saif had the authority to approve payments on building contracts, single-handedly disbursing six-figure sums. In addition, Saif took his savings and invested in a restaurant, bringing in Salar and another friend as minority partners. The threesome leased a modest two-story establishment in Zawra Park, an expanse of green near Mansour that contains gardens, a playground, waterfalls, artificial rivers, cafeterias and an expansive zoo. The restaurant had a seating capacity of about 75, and it was full almost every evening: Families flocked there for pizzas and hamburgers, while young men gathered on the rooftop terrace to smoke shishas and drink tea. “It was a good time for us,” said Salar, who helped manage the restaurant during sojourns in Baghdad.

Then, in 2014, Sunni militias in Anbar Province rose up against the Shia-dominated Iraqi government and formed an alliance with the Islamic State, giving the jihadists a foothold in Iraq. They soon advanced across the country, seizing Mosul and threatening Baghdad. Shia militias coalesced to stop the jihadist advance. Almost overnight, Iraq was thrust back into a violent sectarian atmosphere. Sunnis and Shias again looked at each other with suspicion. Sunnis could be stopped on the street, challenged, and even killed by Shias, and vice versa.

For two young men just out of college trying to build normal lives, it was a frightening turn of events. One night, as Salar drove back to Baghdad through Anbar Province from his job on the Syrian border, masked Sunni tribesmen at a roadblock questioned him at gunpoint. They ordered Salar out of the vehicle, inspected his documents, and warned him not to work for a company with government connections. Months later came an even more frightening incident: Four men grabbed Salar off the street near his family’s home in Mansour, threw him into the back seat of a car, blindfolded him and took him to a safe house. The men—from Shia militias—demanded to know what Salar was really up to along the Syrian border. “They tied me up, they hit me,” he says. After two days they let him go , but warned him never to travel to the border again. He was forced to quit his job.

The Shia militias, having rescued Baghdad, were becoming a law unto themselves. In 2014, at the Baghdad Governorate, a supervisor demanded that Saif authorize a payment for a school being built by a contractor with ties to one of the most violent Shia groups. The contractor had barely broken ground, yet he wanted Saif to certify that he had finished 60 percent of the work—and was entitled to $800,000. Saif refused. “I grew up in a family that didn’t cheat. I would be held responsible for this,” he explained. After ignoring repeated demands, Saif left the documents on his desk and walked out for good.

The militia didn’t take the refusal lightly. “The day after I quit, my mother called me and said, ‘Where are you?’ I said, ‘I’m in the restaurant, what’s up?’” Two black SUVs had pulled up outside the house, she told him, and men had demanded to know, “Where is Saif?”

Saif moved in with a friend; gunmen cruised past his family’s house and riddled the top floor with bullets. His mother, father and siblings were forced to take refuge at Saif’s uncle’s home in Mansour. Militiamen began searching for Saif at the restaurant in Zawra Park. Unhappy about the thugs who came by searching for Saif—and convinced that he could make more money from other renters—the building’s owner evicted the partners. “I started thinking, ‘I have to get out of here,’” Saif says.

Salar, too, had grown weary: the horror of ISIS, the thuggery of the militias, and the waste of his engineering degree. Every day scores of young Iraqi men, even entire families, were fleeing the country. Salar’s younger brother had escaped in 2013, spent months in a Turkish refugee camp, and sought political asylum in Denmark (where he remained unemployed and in limbo). Both men had relatives in Germany, but worried that with so many Syrians and others heading there, their prospects would be limited.

The most logical destination, they told each other as they passed a water pipe back and forth at a café one evening, was Finland—a prosperous country with a large Iraqi community and plenty of IT jobs. “My mother was afraid. She told me, ‘Your brother left, and what did he find? Nothing.’ My father thought I should go,” Salar says. Saif’s parents were less divided, believing the assassins would find him. “My parents said, ‘Don’t stay in Iraq, find a new place.’”

In August, Saif and Salar paid an Iraqi travel agency $600 apiece for Turkish visas and plane tickets to Istanbul, and stuffed a few changes of clothes into their backpacks. They also carried Iraqi passports and their Samsung smartphones. Salar had saved $8,000 for the journey. He divided the cash, in hundreds, into three plastic bags, placing one packet in his underpants, and two in his backpack.

Salar also gathered his vital documents—his high-school and college diplomas, a certificate from the Ministry of Engineering—and entrusted them to his mother. “Send this when I need them. I will tell you when,” he told her.

Not far away, Saif was planning his exit. Saif had just $2,000. He had spent almost everything he had investing in the restaurant and supporting his family; he promised to repay Salar when they got established in Europe. “I was living at my friend’s house, in hiding, and Salar came to me, and I had packed a small bag,” he says. “We went to my uncle’s house, saw my father, my mother and my sisters, and said farewell.” Later that morning, August 14, 2015, they took a taxi to Baghdad International Airport, hauling their baggage past three security checkpoints and bomb-sniffing dogs. By noon, they were in the air, bound for Istanbul.

For a man who has been through

bitter experiences andtraveled far can enjoy even his

sufferings after a timeBook 15

**********

Istanbul in the summer of 2015 was crowded with refugees from across the Middle East, South Asia and Africa, lured to this city on the Bosphorus because it served as a jumping off point to the Aegean Sea and the “Balkan Route” into Western Europe. After spending two nights in an apartment with one of Saif’s relatives, Salar and Saif found their way to a park in the city center, where Iraqi and Syrian refugees gathered to exchange information.

They led the pair to a restaurant whose owner had a side business organizing illegal boat trips across the Aegean. He took $3,000 from Salar to secure two places—then handed them off to an Afghan colleague. The man led them down a flight of steps and unlocked a basement door. “You will wait in here just a little while,” he assured Salar in Kurdish. (Salar had learned the language from his mother, a Kurdish Shia.) “Soon we will take you by car to the departure point.”

Salar and Saif found themselves sitting amid 38 other refugees from all over the world—Iran, Syria, Mali, Somalia, Eritrea, Iraq—in a Cyclopean cellar wrapped in near-total darkness. The single light bulb was broken; a trickle of daylight pierced a window. The hours passed. No food appeared. The toilet began to stink. Soon they were gasping for air and bathed in sweat.

For a day and a night the refugees languished in the basement, pacing, crying, cursing, begging for help. “How much longer?” demanded Salar, who was one of the few people in the basement who could converse with the Afghan. “Soon,” the man replied. The Afghan went out and returned with thick slices of bread and cans of chickpeas, which the famished refugees quickly devoured.

Finally, after another day and night of waiting, Saif and Salar, with other Iraqi refugees, decided to act. They backed the Afghan into a corner, pinned his arms behind his back, seized his keys, opened the door and led everybody outside. They marched back to the restaurant, found the owner—and demanded he put them on a boat.

That night a smuggler packed Salar and Saif into a van with 15 others. “All the people were squeezed into this van, one on top of the other,” Salar remembers. “I was sitting between the door and the seats, one leg down, my other leg up. And nobody could change positions.” They reached the Aegean coast just at dawn. The Mytilene Strait lay directly in front of them, a narrow, wine-dark sea that divided Turkey from Lesbos, the mountainous Greek island sacked by Achilles during the Trojan War. Now it served as a gateway for hundreds of thousands of refugees lured by the siren song of Western Europe.

In good weather, the crossing typically took just 90 minutes, but the graveyards of Lesbos are filled with the bodies of unidentified refugees whose vessels had capsized en route.

Four hundred refugees had gathered on the beach. Smugglers quickly pulled seven inflatable rubber dinghies out of boxes and pumped them full of air, clamped on outboard motors, distributed life jackets, and herded people aboard. The passengers received brief instruction—how to start the motor, how to steer—then set out by themselves. One overloaded vessel sank immediately. (Everyone survived.)

Salar and Saif, too late to secure a place, dove into the water and forced their way aboard the fourth boat filled with about 40 members of an Iranian family. “The weather was foggy. The sea was rough,” Saif remembers. “Everybody was holding hands. Nobody said a word.” They had decided that they would try to pass themselves off as Syrians when they landed in Greece, reasoning that they would arouse more sympathy from European authorities. The two friends tore up their Iraqi passports and threw the shreds into the sea.

The island appeared out of the fog, a few hundred yards away. One refugee turned off the engine and told everyone to jump off and wade ashore. Saif and Salar grabbed their packs and plunged into the knee-deep water. They crawled up on the beach. “Salar and I hugged each other and said ‘Hamdullah al Salama.’” [Thanks to God.] Then, together, the refugees destroyed the dinghy, so that, Salar explained, it couldn’t be used by Greek authorities to send them back to Turkey.

They trekked 11 hours through a wooded country with mountains wrapped in mist. The scorching August sun beat down on them. At last they reached a refugee camp in the capital, Mytilene. The Greeks registered them and herded them onward. They caught a midnight ferry to Kavala on the mainland, and traveled by bus and taxi to the border of Macedonia.

Just the day before, Macedonian security forces had used shields and truncheons to beat back hundreds of refugees, and then strung barbed wire across the border. As news reporters descended on the scene, the authorities capitulated. They removed the wire, allowing thousands more—including Salar and Saif—to cross from Greece into Macedonia. A Red Cross team conducted medical checks, and passed out chicken sandwiches, juice and apples to the grateful and weary throng.

The next day, after trekking the countryside, then taking an overnight train and a bus, they reached Belgrade in Serbia. A student rented them a room and introduced them to Marco, the Serb with contacts in the smugglers’ world.

After the smugglers abandoned them at the rest stop, the two friends stumbled to Subotica, then made their way by bus two hours back to Belgrade. At Marco’s place, Salar, a pacifist with a strong aversion to violence, tried to assume a threatening posture and demanded that Marco refund their money. “If you don’t, I will burn your apartment and I will sit and watch,” he warned.

Marco repaid them and introduced them to a Tunisian guide who took $2,600 and dropped them on a forest trail near the Hungarian border. They opened the fence at night with wire cutters, scrambled through, and paid $1,000 for a ride through Hungary, and another $800 for a ride through Austria. The police finally caught them during a sweep through a train heading north through Germany. Ordered off in Munich along with dozens of other refugees, they were herded onto a bus to a holding center in a public gymnasium. German authorities digitally scanned their fingerprints and interviewed them about their backgrounds.

Only days earlier, Chancellor Merkel had eased restrictions on refugees trying to enter Germany. “Wir schaffen das,” she had proclaimed at a press conference—“We can do it”—a rallying cry that, initially at least, most German citizens greeted with enthusiasm. Abandoning the notion of reaching Finland, Salar begged a friendly German official to dispatch them to Hamburg, where an aunt lived. “Hamburg has filled its quota,” the official said. Salar’s second choice was Berlin. She could do that, she said, and handed them documents and train tickets. A van transported them to Munich’s central station for the six-hour journey to the German capital. They had been on the road for 23 days.

Nobody is my name

Book 9

**********

Before midnight on Saturday, September 5, 2015, the two young Iraqis disembarked from the Intercity Express train at Berlin Hauptbahnhof, the capital’s central station, a ten-year-old architectural marvel with an intricately filigreed glass roof and a glass tunnel that connects four gleaming towers. The Iraqis stared in wonder at the airy, transparent structure. With no idea where to go or what to do, they asked a police officer on the platform for help, but he shrugged and suggested they look for a hotel. At that moment, two German volunteers for a refugee aid agency, both young women, approached the two Iraqis.

“You guys look lost. Can we help you?” one asked in English. Relieved, Salar explained the situation. The volunteers, Anne Langhorst and Mina Rafsanjani, invited the Iraqis to spend the weekend in the guest room of Mina’s apartment in Moabit, a gentrifying neighborhood in northwestern Berlin, a 20-minute subway ride from the central station. It was just a short walk, they said, to the Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales, or LaGeSo (State Bureau for Health and Social Services)—the Berlin agency responsible for registering and taking care of refugees. Anne, a graduate student in foreign affairs in Berlin and the daughter of physicians from a town near Düsseldorf, promised to take them there on Monday, as soon as the agency opened.

Three days later, Saif and Salar found a mob standing in front of LaGeSo headquarters, a large concrete complex across the street from a park. The staff was overwhelmed, struggling to cope with the flood of humanity pouring in after Merkel lifted restrictions on refugees. The two Iraqis managed to push their way inside the building after an hour, were issued numbers and were ushered into a waiting area in the inner courtyard.

Hundreds of refugees from all over the world packed the grassy space. All had their eyes glued to a 42-inch screen that flashed three-digit numbers every two minutes. The numbers didn’t flow in sequence, so the refugees had to keep watching, trading off with friends for bathroom breaks and food runs.

For 16 days, Salar and Saif held vigil in the courtyard from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., returning to Mina’s house for the night. Then, on the afternoon of day 17, as Salar was dozing, Saif nudged him awake. “Salar, Salar,” he shouted. “Your number!” Salar leapt up, raced inside the building, and emerged triumphantly with his registration document. He sat with Saif until his number came up—seven days later.

Salar and Saif found Berlin to be a congenial city, filled with all the things that Baghdad sorely lacked—verdant parks, handsome public spaces, an expansive and efficient public transit system, and above all, a sense of security. But even after making it past this critical step at LaGeSo, they faced new obstacles, new frustrations. The initial government subsidy—€560 for the first three months—was barely enough to survive. German language classes in Berlin were already filled. They shuttled by streetcars and subways from hostel to hostel, only to find that managers wouldn’t rent rooms to refugees because LaGeSo took so long to pay the bill. (Luckily, Mina had told them to stay in her apartment as long as necessary.) Salar and Saif longed to work, but the temporary registration prohibited them from holding a job. To fill their days, Salar and Saif played soccer with other refugees in parks around the city.

Salar’s English proved to be invaluable in Berlin, where nearly every educated person under 50 is at least conversant in the language. Saif, who was unable to speak any English, felt increasingly isolated, lost and dependent on his friend. Sometimes, waiting in line at LaGeSo for his monthly handout, or a voucher for a doctor’s appointment, Saif even began to talk in frustration about returning to Baghdad.

Salar begged him to be patient, reminding him why he had fled in the first place. “From day one, Salar said to me, ‘I will only go back to Iraq when I’m dead,’” says Anne, drawing a contrast between the two men’s psychological states. Saif “wasn’t prepared. He went into the whole thing as a big adventure. And then the language difficulty [and] the humiliation of standing in line for money and other assistance wore him down.” Anne recalls how “he would force himself to say ‘I will learn German, I will find a job,’ and then he would lose his resolve. Saif’s mother called Salar once and said, ‘I can’t stand it anymore, he needs to make a decision.’” For his part, Saif insists that he was well-prepared for setbacks. “I knew that I was going to Germany not as a tourist,” he says. “I knew you had to be patient, you had to wait. My uncle in Germany had already warned me that it would take a long time.”

Just before New Year 2016, Salar and Saif received one-year German registration cards, giving them permission to travel within Germany, raising their stipend to €364 a month, and providing them with a bank account, medical insurance and permission to seek employment. They were slowly gaining more independence: Salar finally found them a double room in a hostel in Prenzlauer Berg, an affluent neighborhood in eastern Berlin. They started twice-weekly German classes with a volunteer teacher. And Salar’s job prospects in particular were looking good: First he landed an internship with a Berlin software company. Then Siemens, the electronics giant, interviewed him for a job developing a website to guide refugees to job opportunities, and invited him back for a second round.

By a stroke of bad luck, Salar took a hard fall playing soccer, and fractured his leg days before the second interview. Forced to cancel the appointment, he didn’t get the position, but he had come close, and it boosted his self-confidence. And his friendship with Anne provided him with emotional support.

Saif, meanwhile, kept getting dragged back, psychologically, to Iraq. Twice-daily Skype calls to his family from his room in the hostel left him heartbroken and guilty. He was tormented by the thought of his aging parents hunkering down in the uncle’s crowded house in Mansour, too frightened to go out—all because he had refused to authorize the illegal payment to the Shia militia. “People are intimidating us, following us,” his brother told him. Saif seemed irresistibly drawn to his homeland. Like Odysseus, gazing toward Ithaca from the beach of Ogygia, the island where Calypso held him captive for seven years, “His eyes were perpetually wet with tears....His life draining away in homesickness.”

Then, one day early in 2016, Saif received a call from his sister. She and her husband had gone the previous night to check on the family house in Mansour, she told him, voice breaking. She had been playing with her 1-year-old son when someone knocked on the door. Her husband went to answer it. When he didn’t return after ten minutes, she went outside—and found him lying in a pool of blood. He had been shot in the head and killed. It wasn’t clear who had murdered him—but the sister had little doubt that the thwarted contractor was taking revenge on Saif by targeting members of his family.

“Because of you,” she said, sobbing, “I have lost my husband.”

Saif hung up the phone and wept. “I told the story to Salar, and he said, ‘Don’t worry, it’s a lie.’ He was trying to keep me calm.” Saif’s brother in Baghdad later confirmed to Salar that the brother-in-law had indeed been murdered. But fearful that Saif might rush back and put his life in jeopardy, Salar and Saif’s brother agreed that Salar should keep pretending that the story was false, concocted by family members to bring Saif back to Baghdad.

But Salar’s effort didn’t work. One January morning, while Salar was asleep, Saif traveled by subway across Berlin to the Iraqi Embassy in the affluent Dahlem neighborhood and obtained a temporary passport. He bought a ticket to Baghdad, via Istanbul, leaving the next night. When he told Salar that he had made up his mind to leave, his best friend exploded.

“Do you know what you are going back to?” he said. “After all that we’ve suffered, you’re giving up? You need to be strong.”

“I know we took the risk, I know how difficult it was,” Saif replied. “But I know that something is very wrong in Baghdad, and I cannot be comfortable here.”

Salar and Anne accompanied him by bus to Tegel Airport the next evening. Four Iraqi friends boarded the bus with them. In the terminal, they followed him to the Turkish Airlines check-in counter. Saif seemed confused, even distraught, pulled in two directions. Perhaps, Anne thought, he would have a change of heart.

“I was crying,” Saif recalled. “I had done the impossible, just to get to Germany. Leaving my best friend [seemed unimaginable]. I thought, ‘Let me give it one more try.’” Then, to the astonishment of his friends, Saif ripped up his passport and his plane ticket and announced he was staying. “We all hugged, and then I came back to the hostel with Salar and Anne, and we hugged again.”

But Saif couldn’t get the dark thoughts, the self-doubt, out of his mind. Three days later, he obtained yet another Iraqi passport, and a new ticket to return home.

“No. Don’t. We are friends. Don’t leave me,” Salar pleaded, but he had grown tired of his friend’s vacillations, and the energy had gone out of his arguments.

“Salar, my body is in Germany, but my soul and my mind are in Baghdad.”

The next morning, while Salar was at a German class, Saif slipped away. “I was riding past the streets [where we had walked], and the restaurants where we had eaten together, and I was crying,” he recalled. “I was thinking about the journey we had taken. The memories flooded my mind, but I was thinking about my family as well. I sat on my emotions and I said, ‘Let me return.’”

The wind drove him on,

the current bore him here...

And I welcomed him warmly,

cherished himBook 5

**********

Three months after Saif’s return to Baghdad, Salar and I met for the first time at a café in Moabit, not far from the LaGeSo headquarters. Salar’s leg was still encased in a cast from his winter soccer accident, and he hobbled down the sidewalk on crutches from the U-Bahn station, accompanied by Anne. A mutual friend had put us in touch, after I had called him for help finding refugees who had given up and returned home. Salar, chain-smoking over cups of tea as we sat at an outdoor table on a warm spring evening, began telling the story of his journey with Saif, his life in Berlin and Saif’s decision to return to Baghdad. “I fear for him, but I have to concentrate on my own life now,” he told me. He was still living in the hostel, but he was eager to find his own apartment. Salar had been to two interviews with rental agents, and each had left him feeling self-conscious and inadequate. “When you have a job you are comfortable to talk to them,” he told me. “But when you go there as a refugee, and tell them ‘LaGeSo pays for me,’ you are shy. You feel ashamed. I cannot deal with that, [because] maybe they will laugh.” After the interviews that went nowhere, he had given up the search.

Then, in June 2016, Anne heard about an American woman living in the States who owned a studio apartment in Neukölln, a lively neighborhood in eastern Berlin with a large Middle Eastern population. Her current renter was moving out, and the place would soon become available. The rent was €437 a month, €24 above LaGeSo’s maximum subsidy, but Salar was happy to pay the difference. A half-hour interview with the owner on Skype sealed the deal.

I met him in the fourth-floor walk-up in early July, just after he moved in. A septuagenarian uncle from Mannheim, who was visiting for the weekend, was snoring on a foldout couch in the sparsely furnished living room. Salar was ecstatic to be on his own. He brewed tea in his tiny kitchen and pointed out the window at the maple-lined street and, across the way, a grand apartment house with a neo-Baroque facade. “For a single guy in Germany this is not so bad,” he told me.

Salar’s integration into German society continued apace. We met again one July evening at an Iraqi-owned falafel restaurant on Neukölln’s Sonnenallee, a crowded thoroughfare lined with Middle Eastern cafés, tea shops and shisha bars. An Arab wedding convoy rode past, horns blaring, cars garlanded with pink and red roses. Salar said he had just returned from a one-week holiday in the Bavarian Alps with Anne and her parents. He showed me photos on his Samsung of green valleys and granite peaks. He had found a place in a subsidized German language class that met for 20 hours each week. He was gathering documents from home in Baghdad to apply for certification in Germany as a software engineer.

And he was excited about new legislation that was working its way through the German Parliament, making it easier for refugees to find a job. Until now, asylum seekers have been barred from being hired if Germans or other European workers can fill the position, but the restriction is being removed for three years. He was philosophical about the long road ahead. “You are born and grow up in a different country,” he said that evening. “But I don’t have another solution. I will never return to Iraq to live. The situation is maybe hard at the beginning until you get accepted, but it’s good after that. Germany is a good country.”

Yet ten months after his arrival, he was still waiting to be summoned for his interview for asylum—an hours-long interrogation by an official from Germany’s Federal Office for Migration and Refugees that would determine if he would be able to stay permanently in Germany. The day before I met him on Sonnenallee, an Iraqi friend who had arrived two months before Salar and Saif had lost his bid for asylum. The friend could buy himself a year or two while his lawyers pressed his case through the courts, but if two appeals were rejected, he would face immediate deportation. (Political attitudes in Germany are hardening, and deportations of asylum seekers rose from 20,914 in 2015 to 25,000 in 2016; 55 percent of Iraqis who sought asylum last year were denied.) “Of course it makes me worried for myself,” Salar said, as he washed down his falafel with a glass of ayran, a Turkish salty yogurt drink. With Anne’s help, he had hired an attorney at Kraft & Rapp, a reputable Berlin firm, to help him prepare for the interview.

In September I got a call from Salar: His interview had been scheduled for the following Monday morning at 7:30. I met him, Anne and Meral, an assistant from the law firm, at daybreak at the U-Bahn station at Hermannplatz, down the street from his apartment. Salar had gelled his hair and dressed for the occasion, with a short-sleeved, plaid button-down shirt, pressed black jeans and loafers. He clutched a thick plastic folder filled with documents—“my life in Iraq and in Germany,” he said—and huddled with Meral on the subway as we headed to the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees in western Berlin.

He had rehearsed with her the details of his story—the masked Sunni militants along the border, the abduction in Baghdad—and had backed up his tale with a Baghdad police report and threatening messages sent to him via the messenger app Viber, all professionally translated into German. He had even printed out a screen shot of a Shia militiaman brandishing a Kalashnikov—sent to him by one of his kidnappers. “He has a strong case,” Meral told me. “He has plenty of proof that his life would be in danger if he returned to Iraq.”

About 30 refugees and a few attorneys were waiting in front of the agency when we arrived. Salar lit a cigarette and shivered in the autumn chill. Meral told him to be prepared for a grueling day: Some refugees had sat in the waiting room for five or six hours before their interview, which could last another five hours. Four people would be present for the meeting: Salar, Meral, the interviewer and a German-Arabic interpreter. It would take several months before Salar received an answer.

A security guard opened the door and beckoned to Salar and Meral. “I’m not nervous,” he insisted, slipping inside. “I just wish that Saif could be here too.”

Winter approached, and Salar waited for an answer. On Thanksgiving Day, he and Anne joined my family at our apartment in Berlin for turkey, sweet potatoes and cranberry sauce. He still hadn’t heard a word from his lawyer, he said, as he dug contentedly into his first-ever Thanksgiving meal, but he remained optimistic. Across Europe and the United States, however, the tide was turning against refugees: Donald Trump had won the election, partly by promising to bar citizens of some Muslim-majority nations as a threat to American security. In Hungary, the right-wing government said it was making plans to detain asylum seekers during their entire application process, a contravention of EU rules.

In Germany, the political backlash against Merkel and her refugee policy reached a new level after December 19, when a Tunisian immigrant drove a truck at full speed into a crowded Christmas market in Berlin, killing 12 people. “The environment in which such acts can spread was carelessly and systematically imported over the past one-and-a-half years,” the far-right leader Frauke Petry declared. “It was not an isolated incident and it won’t be the last.” Salar’s anxiety deepened as the New Year began. One after another, Iraqi friends had their asylum requests rejected and were ordered to leave the country.

In late January, President Trump issued the immigration ban that included Iraqis. A relative of Salar’s who has lived in Texas for decades phoned Salar and said he no longer felt safe. He also expressed fears about the future, saying the ban was “creating divisions between Muslims and other people in America,” Salar told me. “I am thinking maybe the European Union will do the same thing.”

It was this past February that Salar called me to say, cryptically, that he had important news. We met on a frigid evening at a shisha bar near his apartment in Neukölln. Over a water pipe and a cup of tea in a dim, smoke-filled lounge, he said his lawyer had called him in the middle of a German class the previous day. “When I saw her number on the screen, I thought, ‘uh-oh, maybe this is a problem.’ My heart was pounding,” he told me. “She said, ‘You got your answer.’” Salar pulled a letter from his pocket and thrust it in my hands. On the one hand, German authorities had denied him political asylum. On the other hand, because of the danger he faced from the militiamen who had kidnapped him and threatened his life in Baghdad, he had received “subsidiary protection.” The new status gave Salar the right to remain in Germany for one year with additional two-year extensions, with permission to travel in the European Union. The German government reserved the right to cancel his protection status and deport him, but, according to his lawyer, as long as he continued learning German and found a job, he had an excellent chance to obtain permanent residency—a path to German citizenship. “On the whole, the news is very positive,” he said.

Salar was already making plans to travel. “I will go to Italy, I will go to Spain, I will go everywhere,” he exulted. As a sign of its confidence in him, the German government had offered him a scholarship for a graduate program in IT engineering, and he expected to begin his studies in the spring. His German was fast improving; Anne was speaking to him almost exclusively in her native language. He had even found time to study guitar for a few hours a week, and would be playing his first song—John Lennon’s “Imagine”—at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate in the middle of February.

Let him come late,in bad case, with the lossof all his companions,in someone else’s ship,and find troubles in his household.Book 9

**********

The sky was a leaden gray and the temperature pushing 110 degrees as I inched with my driver-interpreter through traffic across the Al-Jamhuriya Bridge, an ugly steel-and-concrete span over the Tigris. Slate gray and murky, the river flowed sluggishly past sand banks and palm trees, their fronds wilting in the mid-August heat. Baghdad revealed itself in a harsh landscape of blast walls, piles of rubble, cylindrical watchtowers, military check points and posters of martyrs who had died fighting the Islamic State. A Ferris wheel stood, immobilized, in Zawra Park, the green expanse at the edge of Mansour where Saif and Salar had run their restaurant. We parked outside a concrete house with grimy windows behind a metal fence.

Salar had told Saif the previous week that I was coming out to visit him, and Saif had replied that I would be welcome. Implicit was the hope that I might somehow pull strings and undo the decision he’d made; Saif, Salar said, was still in danger and desperate to leave again. He stepped into the street to greet us. He was solidly built, handsome, with a neatly trimmed beard and mustache and an aquiline nose; he hugged me as if greeting an old friend, and I handed over a parcel from Salar filled with small gifts. Saif led us into a sitting room, furnished with fake-gilt-edged chairs and sofas. A stand-alone air conditioner rattled in the corner.

He recalled the night that he had arrived in Baghdad, after a flight from Berlin to Erbil. Saif was glad at finding himself in his own country, but the elation wore off quickly. “As soon as I stepped out of the airport, I regretted what I had done,” he admitted. “I knew it was the wrong choice.” He caught a taxi to the house where his family was hiding out, and caught them unawares. “When I walked into the house, my sister started screaming, ‘What are you doing here?’ My mother was sick in bed. She started crying, asking ‘Why did you come back? You are taking another risk, they may chase you again.’ I told her, ‘I’m not going to leave the house. I’m not going to tell anybody that I’m here.’”

Seven months later Saif was still living basically incognito. Iraq had become more stable, as the Iraqi Army, the Kurdish forces known as peshmerga and the Shia militias had driven the Islamic State out of most of the country (a factor often cited by Iraqi refugees as a motive for returning). At that very moment the forces were converging on Mosul, the last stronghold of the Islamic State, for a final drive against the terrorist group.

But in Baghdad, Saif’s troubles seemed unending. He had heard that his tormentors were still looking for him. He had told only one friend he was back, steered clear of his neighbors, and even posted fake Facebook updates using old photos taken of him in Berlin. Each week, he said, he wrote on his Facebook page: “Happy Friday, I miss you my friends, I’m happy to be in Germany.” He had found a job in construction in a largely Sunni neighborhood where he didn’t know a soul, taking a minibus to work before dawn and returning after dark. He stayed home with his family at night. It was, he admitted, a lonely existence—in some ways made even more painful by his daily phone call to Salar. “To live in exile, to suffer together—it makes your friendship even stronger,” he said.

The coming months would bring little to change Saif’s predicament. In February, while Salar was celebrating his new government-sanctioned status in Berlin, Saif was still posting phony Facebook messages and hiding from the militia, convinced that he remained a target. Late one night, a hit-and-run driver smashed into Saif’s car as he drove through Mansour. Saif walked away from the collision uninjured, but his car was destroyed, and he suspected that the crash had been deliberate.

“He has no place in the world where he could be happy now,” says Anne, who stays in touch with him.

I asked Salar if it was really possible that Shia militias would maintain their grudge against him for so long. “Of course,” he said. “In Iraq you can never be sure 100 percent that you are safe.”

Toward sunset on my second evening in Baghdad back in August 2016, we drove to the Beiruti Café, a popular shisha bar on a bend in the Tigris. A massive suicide bomb had gone off in central Baghdad a few weeks earlier, killing nearly 300 people—a reminder that the Islamic State, though diminished, was still capable of unspeakable violence. But Iraqis’ desire for normality had trumped their fear, at least for the moment, and the riverside café was packed. It was a rare outing for Saif aside from his trips to work. We stepped into a motorboat at the end of a pier and puttered upstream, passing clumps of dead fish, a solitary swimmer and an angler pulling in his net. Saif smiled at the scene. “This is a cup of tea compared to the Aegean,” he said as multicolored lights twinkled in a string of shisha bars along the river.

After serving us a meal of biryani chicken and baklava at his home that evening, Saif stepped out of the room. He returned holding his curly-haired, 18-month-old nephew, the son of his murdered brother-in-law. “I have to take care of my nephew because he lost his father,” he said. “I feel like he is my son.”

The little boy had given him a sense of purpose, but Saif was in a bad place. He had relinquished his one shot at living in Europe—tightening asylum laws made it unlikely he would ever be able to repeat the journey—yet he was desperately unhappy back home. The experience had left him disconsolate, questioning his ability to make rational decisions. He was cursed by the knowledge of what might have been possible if he had found the inner strength, like Salar, to remain in Germany.

After the meal, we stepped outside and stood in the dirt street, bombarded by the hum of generators and the shouts of kids playing pickup soccer in the still-hot summer night. Women clad in black abayas hurried past, and across the alley, fluorescent lights garishly illuminated a colonnaded villa behind a concrete wall. I shook Saif’s hand. “Help me, please,” he said softly. “I want to be in any country but Iraq. There is danger here. I am afraid.” I climbed in the car and left him standing in the street, watching us. Then we turned a corner and he disappeared from view.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)