Meriwether Lewis’ Mysterious Death

Two hundred years later, debate continues over whether the famous explorer committed suicide or was murdered

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/monument-for-explorer-Meriwether-Lewis-631.jpg)

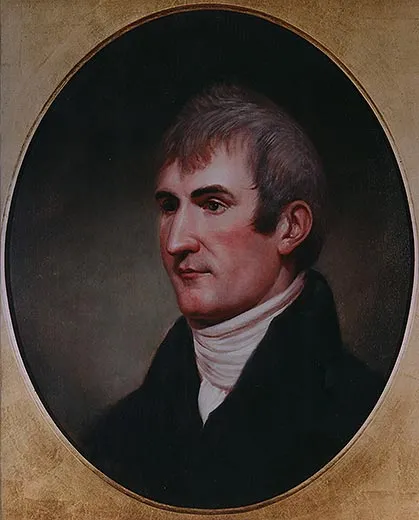

Captain Meriwether Lewis—William Clark’s expedition partner on the Corps of Discovery’s historic trek to the Pacific, Thomas Jefferson’s confidante, governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory and all-around American hero—was only 35 when he died of gunshot wounds sustained along a perilous Tennessee trail called Natchez Trace. A broken column, symbol of a life cut short, marks his grave.

But exactly what transpired at a remote inn 200 years ago this Saturday? Most historians agree that he committed suicide; others are convinced he was murdered. Now Lewis’s descendants and some scholars are campaigning to exhume his body, which is buried on national parkland not far from Hohenwald, Tenn.

“This controversy has existed since his death,” says Tom McSwain, Lewis’s great-great-great-great nephew who helped start a Web site, “Solve the Mystery,” that lays out family members’ point of view. “When there’s so much uncertainty and doubt, we must have more evidence. History is about finding the truth,” he adds. The National Park Service is currently reviewing the exhumation request.

The intrigue surrounding the famous explorer’s untimely death has spawned a cottage industry of books and articles, with experts from a variety of fields, including forensics and mental health, weighing in. Scholars have reconstructed lunar cycles to prove that the innkeeper’s wife couldn’t have seen what she said she saw that moonless night. Black powder pistols have been test-fired, forgeries claimed and mitochondrial DNA extracted from living relatives. Yet even now, precious little is known about the events of October 10, 1809, after Lewis – armed with several pistols, a rifle and a tomahawk – stopped at a log cabin lodging house known as Grinder’s Stand.

He and Clark had finished their expedition three years earlier; Lewis, who was by then a governor of the large swath of land that constituted the Upper Louisiana Territory, was on his way to Washington, D.C. to settle financial matters. By some accounts, Lewis arrived at the inn with servants; by others, he arrived alone. That night, Mrs. Grinder, the innkeeper’s wife, heard several shots. She later said she saw a wounded Lewis crawling around, begging for water, but was too afraid to help him. He died, apparently of bullet wounds to the head and abdomen, shortly before sunrise the next day. One of his traveling companions, who arrived later, buried him nearby.

His friends assumed it was suicide. Before he left St. Louis, Lewis had given several associates the power to distribute his possessions in the event of his death; while traveling, he composed a will. Lewis had reportedly attempted to take his own life several times a few weeks earlier and was known to suffer from what Jefferson called “sensible depressions of mind.” Clark had also observed his companion’s melancholy states. “I fear the weight of his mind has overcome him,” he wrote after receiving word of Lewis’s fate.

At the time of his death Lewis’s depressive tendencies were compounded by other problems: he was having financial troubles and likely suffered from alcoholism and other illnesses, possibly syphilis or malaria, the latter of which was known to cause bouts of dementia.

Surprisingly, he may also have felt like something of a failure. Though the Corps of Discovery had traversed thousands of miles of wilderness with few casualties, Lewis and Clark did not find the Northwest Passage to the Pacific, the mission’s primary goal; the system of trading posts that they’d established began to fall apart before the explorers returned home. And now Lewis, the consummate adventurer, suddenly found himself stuck in a desk job.

“At the end of his life he was a horrible drunk, terribly depressed, who could never even finish his [expedition] journals,” says Paul Douglas Newman, a professor of history who teaches “Lewis and Clark and The Early American Republic” at the University of Pittsburgh. An American icon, Lewis was also a human being, and the expedition “was the pinnacle of Lewis’s life,” Newman says. “He came back and he just could not readjust. On the mission it was ‘how do we stay alive and collect information?’ Then suddenly you’re heroes. There’s a certain amount of stress to reentering the world. It was like coming back from the moon.”

Interestingly, John Guice, one of the most prominent critics of the suicide theory, uses a very different astronaut comparison. Lewis was indeed “like a man coming back from the moon,” Guice notes. But rather than feeling alienated, he would have been busy enjoying a level of Buzz Aldrin-like celebrity. “He had so much to live for,” says Guice, professor emeritus of history at The University of Southern Mississippi and the editor of By His Own Hand? The Mysterious Death of Meriwether Lewis. “This was the apex of a hero’s career. He was the governor of a huge territory. There were songs and poems written about him. This wasn’t just anybody who kicked the bucket.” Besides, how could an expert marksman botch his own suicide and be forced to shoot himself twice?

Guice believes that bandits roaming the notoriously dangerous Natchez Trace killed Lewis. Other murder theories range from the scandalous (the innkeeper discovered Lewis in flagrante with Mrs. Grinder) to the conspiratorial (a corrupt Army general named James Wilkinson hatched an assassination plot.)

Though Lewis’s mother is said to have believed he was murdered, that idea didn’t have much traction until the 1840s, when a commission of Tennesseans set out to honor Lewis by erecting a marker over his grave. While examining the remains, committee members wrote that “it was more probable that he died at the hands of an assassin.” Unfortunately, they failed to say why.

But the science of autopsies has come a long way since then, says James Starrs, a George Washington University Law School professor and forensics expert who is pressing for an exhumation. For one thing, with mitochondrial DNA samples he’s already taken from several of Lewis’ female descendants, scientists can confirm that the body really is Lewis’s (corpses were not uncommon on the Natchez Trace). If the skeleton is his, and intact, they can analyze gunpowder residue to see if he was shot at close range and examine fracture patterns in the skull. They could also potentially learn about his nutritional health, what drugs he was using and if he was suffering from syphilis. Historians would hold such details dear, Starrs says: “Nobody even knows how tall Meriwether Lewis was. We could do the DNA to find out the color of his hair.”

Some scholars aren’t so sure that an exhumation will clarify matters.

“Maybe there is an answer beneath the monument to help us understand,” says James Holmberg, curator of Special Collections at the Filson Historical Society in Louisville, Ky., who has published work on Lewis’s life and death. “But I don’t know if it would change anybody’s mind one way or the other.”

The details of the case are so sketchy that “it’s like trying to grab a shadow,” Holmberg says. “You try to reach out but you can never get a hold of it.” Even minor features of the story fluctuate. In some versions, Seaman, Lewis’s loyal Newfoundland who guarded his master against bears on the long journey West, remained by his grave, refusing to eat or drink. In other accounts, the dog was never there at all.

However Lewis died, his death had a considerable effect on the young country. A year and a half after the shooting, ornithologist Alexander Wilson, a friend of Lewis’s, interviewed Mrs. Grinder, becoming one of the first among many people who have investigated the case. He gave the Grinders money to maintain Lewis’s grave and visited the site himself. There, reflecting on the adventure-loving young man who had mapped “the gloomy and savage wilderness which I was just entering alone,” Wilson broke down and wept.