European Printmakers Had No Idea What Colonial American Cities Looked Like, So They Just Made Stuff Up

To satisfy customers hungry for visions of the British colonies, these artists created wildly imaginative and inaccurate scenes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a4/ba/a4bad452-1dba-4ce7-8d83-7abd805cb2b0/3_boston.png)

People often say that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

At first glance, the rationale behind this expression would seem to have played a critical role in the creative process of many European and American artists, etchers, engravers and lithographers of the 18th and 19th centuries. Printmakers would more often than not base their designs on contemporaneous original paintings or sketches, and sometimes they would include carbon copies of selective features from preexisting prints and incorporate them into their own artwork. This course of action was partly taken in order to cut down on production costs (as opposed to wanting to pay homage to a favorite artist) as it would have been far cheaper to simply copy designs rather than make them from scratch.

Since most printmakers tended to live dangerously close to the bottom end of the profit margin, it is no surprise that many felt the need to take economic shortcuts wherever they could find them. Also, the notion of originality as an essential artistic principle had only just begun to take hold in the 18th century, so most printmakers felt no qualms about copying the work of others.

During the 1770s and 1780s, German engravers Balthasar Friedrich Leizelt and Franz Xaver Habermann created a number of popular vues d'optique, a special kind of print designed to be viewed with an optical device called a zograscope that would make them appear three-dimensional. Many of these prints show various North American places and cities such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Quebec City. While the majority of 18th century city views were ultimately derived from some type of manufactured source (be it a drawing, painting or print), what is peculiar about Leizelt and Habermann’s vues d’optique is that they borrow from preexisting views of European places and cities rather than views of the North American cities they were trying to represent.

Presumably, the German duo did not have access to many (if any) views of North American cities and thus chose to base their designs on views of fashionable European cities instead. The Graphics Division of the Clements Library possesses a grand total of 25 vues d'optique, including a number of prints of North American cities produced by Leizelt and Habermann as part of their "Collection des Prospects" portfolio that was published in Augsburg, Germany, around the time of the American Revolution. These prints have all recently been made available through the University of Michigan Library Catalog Search and will added to the Clements Image Bank in the near future.

A few of Leizelt and Habermann’s vues' d'optique show clear indications of appropriation. For example, features of an engraving based on a painting by Richard Paton (1717-1791) depicting the Royal dockyard at Deptford, England in 1775 appear in two vues d'optique from around 1776 that are credited to Leizelt. These fictionalized views of "Philadelphie" and "La nouvelle Yorck", both depictions of harbor scenes, contain carbon-copy components from the Deptford view and almost certainly borrowed features from other popular views of European harbors.

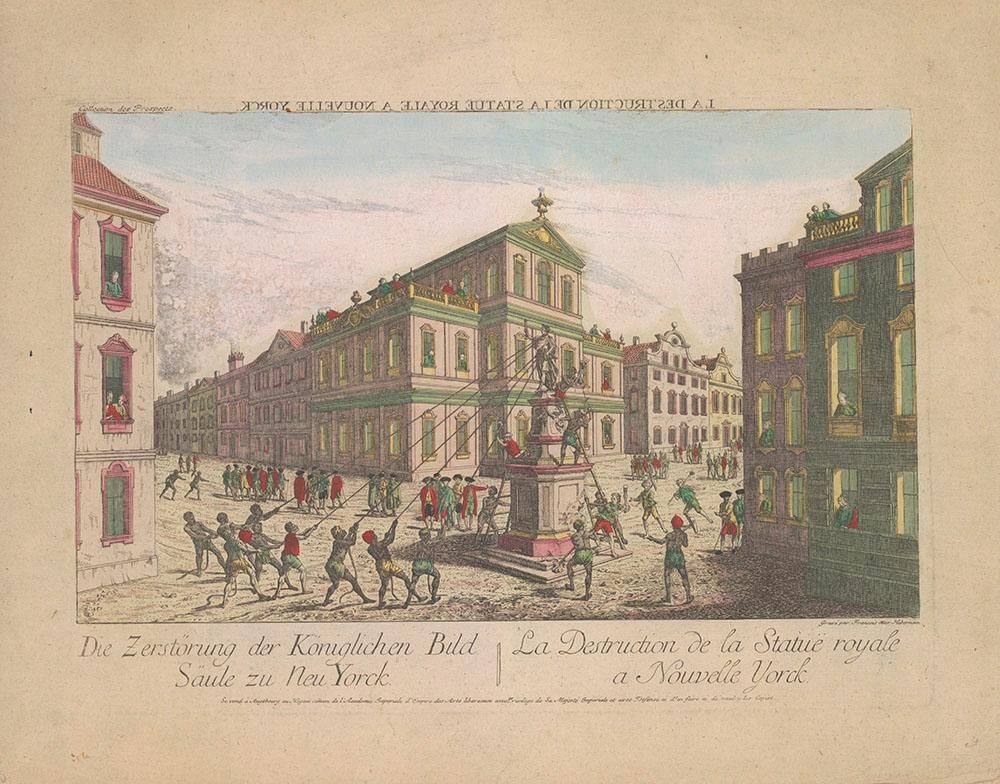

Other vues d'optique that clearly show telltale signs of derivation include Habermann's view of a Presbyterian church on King Street in Boston and his view depicting the statue of George III being torn down in New York City. The former shows a bustling street scene on la Ruë grande in Boston.

However, the buildings that appear in this print do not even remotely resemble anything that would have been present in colonial Boston. In particular, the flamboyantly ornate Presbyterian church sticks out like a sore thumb. The latter view shows a group of individuals (mostly African-Americans) banding together to topple the statue of George III that had been erected in New York in 1770. Again, none of the buildings represented in this view are typical of colonial New York structures, while the statue of George III is also an erroneous depiction. The authentic statue showed George III on horseback and clothed in a Roman toga in the style of the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, whereas the statue in Habermann's view shows the British monarch in Roman garb yet without a steed.

Seeing as the vast majority of Leizelt and Habermann's clientele had likely never visited North America either, the fact that their purported views of American and Canadian cities were entirely fictitious would have flown under most people's radar. Besides, the primary utility of the vue d'optique was not necessarily to serve as an accurate representation of a city or place. Rather, people utilized these prints more as visual entertainment showpieces at social gatherings in which people would take turns looking through the zograscope and being amazed by the vivid color schemes and the three-dimensional optical illusions.

This story originally appeared on the William Clements Library blog.