How the Nazis “Normalized” Anti-Semitism by Appealing to Children

A new museum and exhibit explore the depths of the hatred toward Europe’s Jews

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/2e/f12e772a-b66d-4caa-8c2f-f3ce7cbd1762/nazi-game.jpg)

One night, some 30 years ago, Kenneth Rendell followed the owner of a military shop outside London through a side door into the store. It was pitch black, and Rendell bumped into something. “I’m just standing there waiting for him to turn the lights on and the alarm off,” he says. “When he turned the lights on, it scared the crap out of me.”

Rendell was face-to-face with a mannequin wearing a black uniform of a Nazi SS officer stationed in Dachau. Where other military uniforms tend to be beige and loose-fitting, the Nazi uniform was designed to frighten people with its dark color, silver trim, red swastika armband and the skull that appears beneath the insignia on the cap. “I realized this is propaganda,” he says of the uniform, about midway into a two-and-a-half hour tour of his museum, which sits some 30 minutes west of Boston. “Look at the skull’s head. This is so frightening.”

The uniform was the first German object purchased by Rendell, founder and director of the voluminous and meticulously-curated Museum of World War II in Natick, Massachusetts. His collection numbers 7,000 artifacts and more than 500,000 documents and photographs, and the museum is slated to expand later this year. When visitors round a corner from a section on occupied Europe, they suddenly find themselves opposite the uniform, much like Rendell was 30 years ago.

“I really wanted this to be shocking and in-your-face,” he says. “People don’t go through here quickly. People really slow down.”

Rendell, who grew up in Boston, started collecting as a child. In 1959, he opened the dealership in autographs and historical documents, letters, and manuscripts that he continues to operate. His clients over the years, according to news reports, have included Bill Gates, Queen Elizabeth and the Kennedy family. “I have loved every day since then as the temporary possessor of the written record of mankind’s greatest heroes and villains, as well as the countless individuals who wittingly or unwittingly became a part of the dramas of history,” his website records.

Although Rendell has no family connection to World War II, he has amassed an enormous collection, and his museum, which is slated to begin construction on a new building next year, displays the sobering and terrifying items tastefully. Rather than coming off overly-curated or frivolous, the encounter with that Nazi uniform strikes just the right tone.

One of the messages of both Rendell’s museum, and the New-York Historical Society exhibit “Anti-Semitism 1919–1939” (through July 31) culled from his collection, is that the Holocaust didn’t arise out of nothing; it spawned out of a long and vicious history of European hatred of Jews.

The exhibit, adds Louise Mirrer, the president and CEO of the New-York Historical Society, “is about the ease with which the rhetoric of hatred, directed against a particular group—in this case, of course, the Jews—can permeate a national discourse and become ‘normal’ for ordinary people.”

The exhibit includes several items with Hitler’s handwriting, including an outline from a 1939 speech, posters and newspaper clippings, an original Nuremberg Laws printing, and signs warning that park benches are off limits to Jews.

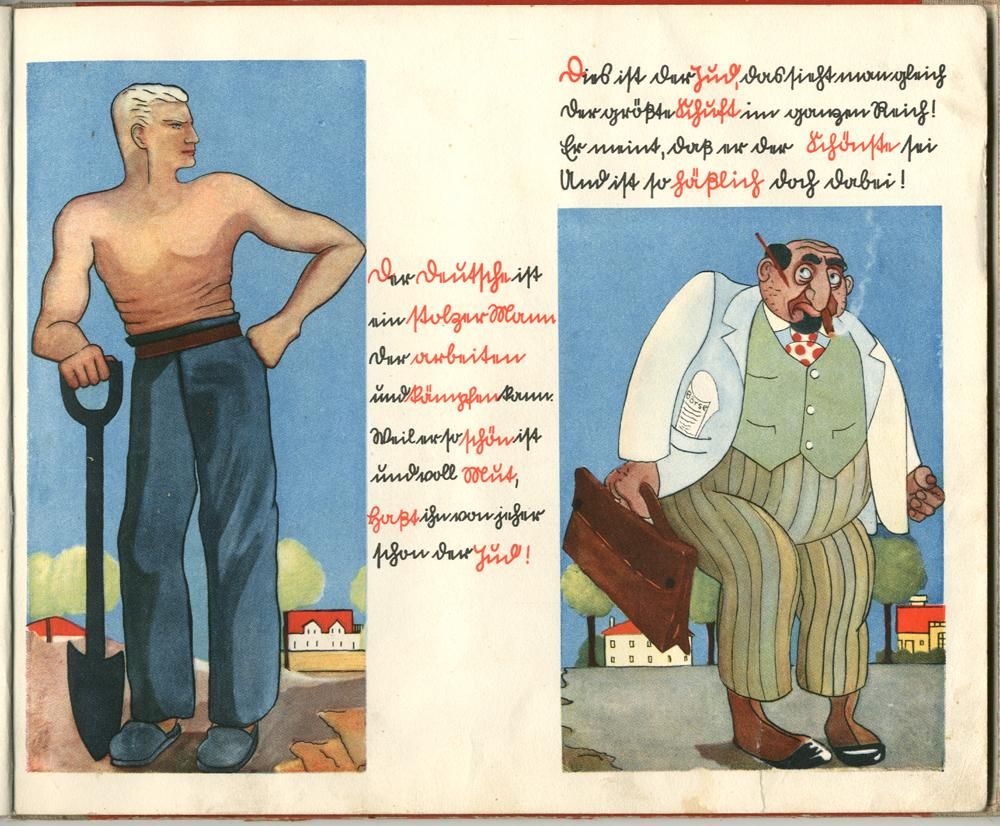

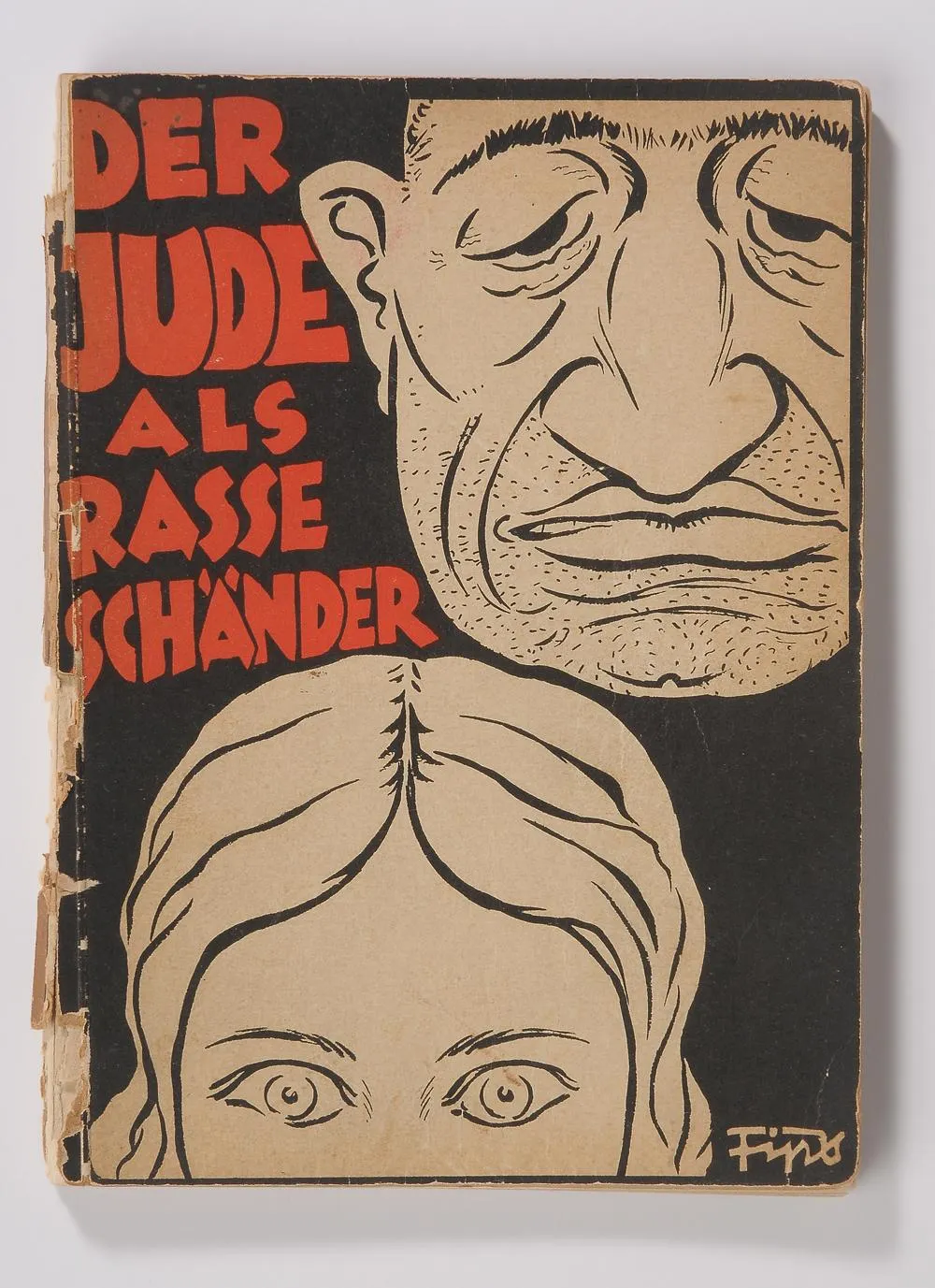

This “normalization,” however, is perhaps most apparent in the hate-filled toys and books designed for children. The exhibit features a 1938 book, whose first page states: “Just as it is often hard to tell a toadstool [a poisonous mushroom] from an edible mushroom, so too is it often very hard to recognize the Jew as a swindler and criminal.” The book, aptly titled The Poisonous Mushroom, adds, “The God of the Jews is money.” The exhibited book opens to an illustration of a blond boy, with basket in hand, holding a mushroom as a woman, evoking Renaissance depictions of saints, points to the fungus.

“The strongest manifestation of anti-Semitism in the exhibition is in the children’s books,” says Mirrer. “Anti-Semitism really has to be introduced at the earliest possible moment in the education of German children.”

Whereas objects in the exhibit, like anti-Semitic faces depicted on ashtrays or walking sticks, where the handle is made of an elongated Jewish nose, reflect longstanding European stereotypical tropes, the children’s books exemplify the culmination of the desensitization that took place leading up to and during World War II.

“You kind of lose the capacity to feel appalled. And then you just believe it,” Mirrer says. “Being exposed to such appalling comparisons over an extended period of time desensitized even the most well-meaning of people, so that comparisons like the Jew and the poisonous mushroom eventually came to seem ‘normal.’”

The children’s books, she adds, proved an effective tool for convincing young Germans that Jews were poisonous to the country. “Children, as we know from research on learning, have to be taught prejudice,” she says.

Rendell agrees. “Hitler Youth recruits were fanatical,” he says. And those who were exposed to the books as children went on to military roles. Rendell’s museum includes in its collections toy soldiers, dolls, and a board game where the pieces move along a swastika.

“Board games and toys for children served as another way to spread racial and political propaganda to German youth,” notes a page on the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s website. “Toys were also used as propaganda vehicles to indoctrinate children into militarism.” The program, which “won over” millions of young Germans, expanded from 50,000 Hitler Youth in January 1933 to 5.4 million youth in 1936, when German authorities disbanded competing organizations for children, the website adds.

Rendell developed a unique collection by pursuing objects related to anti-Semitism at a time when few others sought those sorts of pieces, says Mirrer. “His collection speaks persuasively to our exhibition’s point about how, unchecked, anti-Semitism can spread throughout an entire society,” she says.

Rendell says his museum is the only one he is aware of with a worldwide perspective on World War II. Other countries have national collections and perspectives, because each thinks it won the war, he says. It takes starting with the Versailles treaty, which came down especially hard on Germany, to understand why there was a perceived need in Germany for a resurgence of nationalism.

“Everyone treats the rise of Nazism—that Adolf Hitler is in power,” says Rendell. “But how did he get into power? He ran for office. Twice. They changed anti-Semitism to fit political campaigns.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)