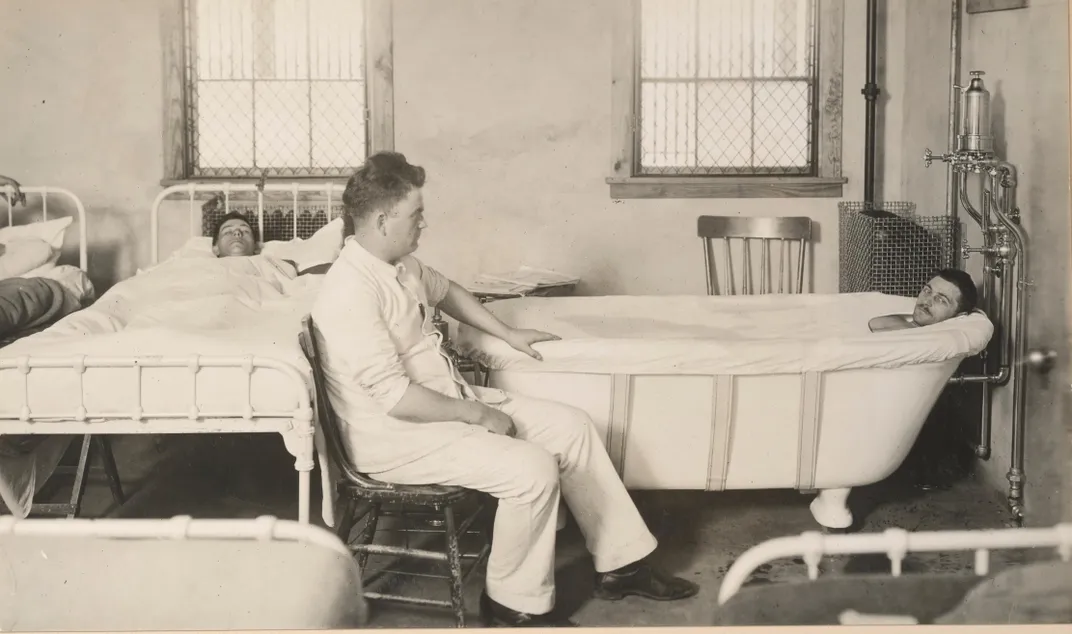

In January 1915, less than a year into the First World War, Charles Myers, a doctor with the Royal Army Medical Corps, documented the history of a soldier known as Case 3. Case 3 was a 23-year-old private who had survived a shell explosion and woken up, memory cloudy, in a cellar and then in a hospital. “A healthy-looking man, well-nourished, but obviously in an extremely nervous condition. He complains that the slightest noise makes him start,” wrote Myers in a dispatch to the medical journal The Lancet. The physician termed the affliction exhibited by this private and two other soldiers “shell shock.”

Shell shock ultimately sent 15 percent of British soldiers home. Their symptoms included uncontrollable weeping, amnesia, tics, paralysis, nightmares, insomnia, heart palpitations, anxiety attacks, muteness—the list ticked on. Across the Atlantic, the National Committee for Mental Hygiene took note. Its medical director, psychiatrist Thomas Salmon, traveled overseas to study the psychological toll of the war and report back on what preparations the U.S., if it entered the ever-swelling conflict, should make to care for soldiers suffering from shell shock, or what he termed “war neuroses.” Today, we recognize their then-mysterious condition as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), an ongoing psychological response to trauma that the Department of Veterans Affairs says affects between 10 and 20 percent of veterans of the United States’ War of Terror.

“The most important recommendation to be made,” Salmon wrote, “is that of rigidly excluding insane, feebleminded, psychopathic and neuropathic individuals from the forces which are to be sent to France and exposed to the terrific stress of modern war.” While his suggestion to identify and exclude soldiers who might be more vulnerable to “war neuroses” seems today like an archaic approach to mental health, it resulted in a lasting contribution to popular psychology: the first personality test.

When Myers named shell shock, it had a fairly short paper trail. During the German unification wars a half-century earlier, a psychiatrist had noted similar symptoms in combat veterans. But World War I introduced a different kind of warfare—deadlier and more mechanized, with machine guns and poison gas. “Never in the history of mankind have the stresses and strains laid upon the body and mind been so great or so numerous as in the present war,” lamented British-Australian anthropologist Elliott Smith.

Initially, the name “shell shock” was meant literally—psychologists thought the concussive impact of bombshells left a mental aftereffect. But when even non-combat troops started exhibiting the same behavioral symptoms, that explanation lost sway. One school of thought, says Greg Eghigian, a history professor at Pennsylvania State University who’s studied the development of psychiatry, suspected shell shock sufferers of “maligning,” or faking their symptoms to get a quick exit from the military. Others believed the prevalence of shell shock could be attributed to soldiers being of “inferior neurological stock,” Eghigian says. The opinion of psychologists in this camp, he says, was: “When such people [with a ‘weak constitution’] get faced with the challenges of military service and warfare, their bodies shut down, they shut down.”

Regardless of shell shock’s provenance, its prevalence alarmed military and medical leaders as the condition sidelined soldiers in a war demanding scores of men on the front lines. To add insult to injury, the turn of the century had brought with it “an increasingly uniform sense that no emotional tug should pull too hard,” writes historian Peter Stearns in his book American Cool: Constructing a Twentieth-Century Emotional Style, and accordingly, seeing soldiers rattled by shell shock concerned authorities. From the perspective of military and medical personnel, Eghigian explains, “The best and brightest of your young men, whom you staked so much on, they seem to be falling ill [and the explanation is] either they’re cowards, if they’re malingers, or they have constitutions like girls, who are historically associated with these kinds of ailments.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cd/1f/cd1f0b67-de0c-4b30-917f-5bc28c687a8d/shell_shock_i_france_1.jpg)

Salmon’s call to screen out enlistees with weak constitutions evidently reached attentive ears. “Prevalence of mental disorders in replacement troops recently received suggests urgent importance of intensive efforts in eliminating mentally unfit from organizations new draft prior to departure from United States,” read a July 1918 telegram to the War Department, continuing, “It is doubtful whether the War Department can in any other way more importantly assist to lessen the difficulty felt by Gen. Pershing than by properly providing for initial psychological examination of every drafted man as soon as he enters camp.”

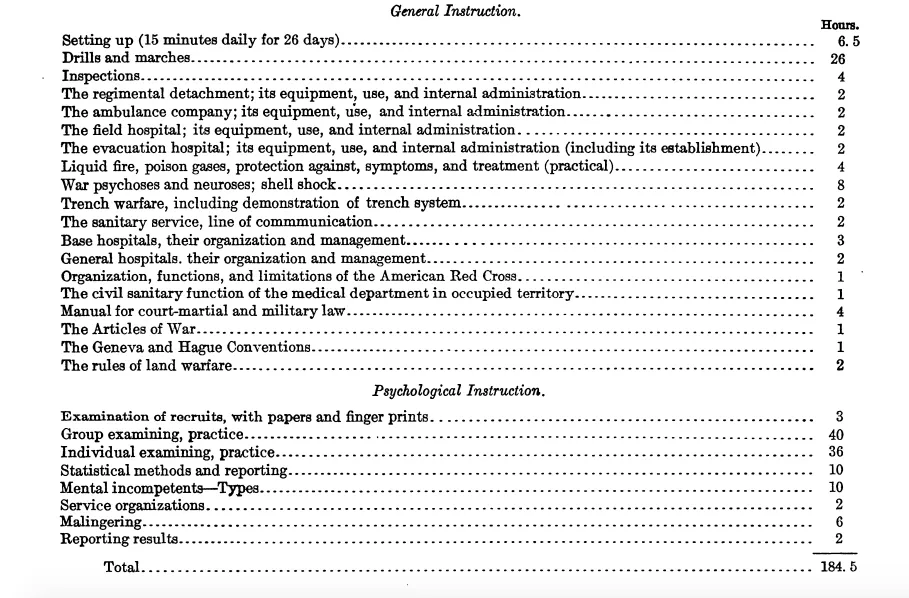

By this point, the United States military had created neuro-psychiatry and psychology divisions and even established a school of military psychology within the Medical Officers Training Camp in Georgia. The syllabus for the two-month training reflects the emphasis placed on preliminary screening (as opposed to addressing the wartime trauma that today’s psychologists would point to as the root cause of many veterans’ PTSD). Of the 365 class hours in the course, 8 were devoted to shell shock, 6 on malingering, and 115 on psychological examination.

Less than two years after the United States entered World War I, around 1,727,000 would-be soldiers had received a psychological evaluation, including the first group of intelligence tests, and roughly two percent of entrants were rejected for psychological concerns. Some of the soldiers being screened, like draftees at Camp Upton in Long Island, would have filled out a questionnaire of yes-no questions that Columbia professor Robert Sessions Woodworth created at the behest of the American Psychological Association.

“The experience of other armies had shown,” Woodworth wrote, “that liability to ‘shell shock’ or war neurosis was a handicap almost as serious as low intelligence…I concluded that the best immediate lead lay in the early symptoms of neurotic tendency.” So Woodworth amassed symptoms from the case histories of soldiers with war neuroses and created a questionnaire, trying out the form on recruits, patients deemed “abnormal,” and groups of college students.

The questions on what would become the Woodworth Personal Data Sheet, or Psychoneurotic Inventory, started out asking if the subject felt “well and strong,” and then tried to pry into their psyche, asking about their personal life—“Did you ever think you had lost your manhood?”—and mental habits. If over one-fourth of the control (psychologically “normal”) group responded with a ‘yes’ to a question, it was eliminated.

Some of the roughly 100 questions that made the final cut: Can you sit still without fidgeting? Do you often have the feeling of suffocating? Do you like outdoor life? Have you ever been afraid of going insane? The test would be scored, and if the score passed a certain threshold, a potential soldier would undergo an in-person psychological evaluation. The average college student, Woodworth found, would respond affirmatively to around ten of his survey’s questions. He also tested patients (not recruits) who’d been diagnosed as hysteric or shell shocked and found that this “abnormal” group scored higher, in the 30s or 40s.

Woodworth had tested out his questionnaire on more than 1000 recruits, but the war ended before he could move on to a broader trial or incorporate the Psychoneurotic Inventory into the army’s initial psychological exam. Nevertheless, his test made an impact—it’s the great-grandparent of today’s personality tests.

“World War I was actually a watershed moment” in terms of psychological testing, says Michael Zickar, a professor of psychology at Bowling Green State University. The idea of applying psychology in a clinical or quantitative way was still relatively novel, but the widespread use of testing in the army during and after the war—to assess intelligence, to determine aptitude for different jobs, to weed out the mentally “unfit”—helped popularize the practice. Other early personality tests, like the 1930 Thurstone Personality Schedule or the 1927 Mental Hygiene Inventory, would often grandfather in questions from previous tests, like Woodworth’s, which meant that they, too, focused on negative emotionality. (While Hermann Rorschach developed his inkblot test in 1921, it wouldn’t pick up in stateside popularity for at least a decade.)

Industrial psychology and the still-prevalent use of personality tests in the workplace also took off. According to Zickar’s research, managers believed “that people who advocated for labor unions were people who were unsettled and neurotic themselves,” and so they administered these early personality tests to stave off labor unrest.

Eventually, personality tests moved beyond a single-minded focus on neuroticism towards the more multi-dimensional testing we see in both clinical and pop psychology today. These tests, Zickar says, start “viewing the person in much more of a complicated lens.” The 1931 Bernreuter Personality Inventory, for example, evaluates a range of personality traits: neurotic tendency, self-sufficiency, introversion or extroversion and dominance or submission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/6b/4e6b40f5-f2ca-457e-8b70-4117a3986f08/psychiatric_evaluation.jpg)

But while personality tests moved forward, the approach towards trauma-related mental health remained in stasis. As Annessa Stagner recounts in a paper in the Journal of Contemporary History, the army discontinued funding shell shock treatment, “reasoning that better screening in the future could negate the problem.” It also transferred financial responsibility for future soldiers affected by war neuroses to the officers who’d recruited them in the first place.

When World War II began, the army again administered psychological tests with the same backwards objective of finding people whose weak mental constitutions might put them at risk in combat. They rejected more soldiers for “neuropsychiatric causes,” but it wasn’t after the Vietnam War, more than 60 years after Woodworth set out to test for shell shock susceptibility, that the definition of PTSD finally entered the D.S.M., the guiding text for psychiatric diagnosis. “You have to wait, really until the 1960s and the 1970s before you have clinicians and experts start to rethink a basic assumption about people who face what we’d call today traumatic events,” says Eghigian.

:focal(2964x1642:2965x1643)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/80/7680a72b-8521-4c6c-b16f-4aaa932c36be/165-ww-479a-019.jpg)